[ad_1]

American poet and writer Edgar Allan Poe is a giant of American literature. The dark, brooding atmosphere of works such as “The Raven” and “Fall of the House of Usher,” the dread and fear evoked by “The Pit and the Pendulum” and the mystery of “The Murders in the Rue Morgue” all testify to a fertile imagination inspired by a sense of despair and preoccupation with death. Poe is known as a master of Gothic horror and the inventor of the modern detective story.

The life of this tormented genius began on January 19, 1809, in Boston, Massachusetts, the son of David and Elizabeth Poe. Upon Elizabeth’s death in 1811, Edgar was taken in by Richmond, Virginia, merchant John Allan, who gave the child his middle name. Poe published his first poems in 1827 after enrolling as a cadet at West Point. After being expelled from the academy, he turned to a career as a writer, editor, and critical reviewer. Poe died on October 7, 1849, in Baltimore, Maryland.

While these are some of the facts that many of us already know, this list taps into ten lesser-known tidbits about this great contributor to American literature.

Related: Ten Unusual Pets Of Famous Writers And Artists

10 Pioneer of Science Fiction

Poe will always be associated with horror and the macabre, eclipsing the contribution he made to the nascent genre of science fiction. Living in an age of scientific and technological progress, he exploited the fascination for discovery and invention in the story “The Unparalleled Adventures of One Hans Pfall,” the tale of a bellows mender trying to escape his creditors by building a balloon and going to the moon. It has all the elements of good science fiction—adventure, space travel, encounters with aliens. It was the inspiration for Jules Verne’s From the Earth to the Moon.

In Poe’s only complete novel, The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket, we follow the hero to the South Pole regions, where he encounters mysterious islands and strange cultures. There is mention of the then-popular Hollow Earth Theory. Jules Verne penned “The Antarctic Mystery” as a sequel to Poe’s abruptly-ended Narrative.

“The Conversation of Eiros and Charmion” is the story of Earth’s annihilation by a comet. “The Facts of the Case of M. Valdemar” explores the use of hypnotism to survive death. “Mellonta Tauta” is a dystopian vision of the year 2848.

Perhaps a fifth of Poe’s output was sci-fi. No wonder Jules Verne acknowledged him as the creator of the “scientific novel” and followed in his footsteps.[1]

9 The Cryptographer

When the Japanese plan to attack Midway during World War II was uncovered in code, it led to the defeat of the Japanese fleet and marked the turning point of the war. The man who led the team of codebreakers, William Friedman, was one of the world’s greatest cryptographers. His inspiration? Edgar Allan Poe, whose short story “The Gold Bug” he had read as a child. “The Gold Bug” had been described as “unequaled as a work of fiction turning upon a secret message.” It is still used as an instruction manual by some modern universities teaching cryptography.

Poe was himself a skilled cryptographer and issued challenges to readers to send him ciphers he would then proceed to crack. One such challenge was posted in a magazine on December 1839, and Poe claimed to have solved every one of the hundred or so substitution, or Caesar, ciphers submitted. One actually stumped him, so he dismissed it as meaningless jargon (it wasn’t—it was solved in 1977). A Caesar cipher is the simplest code, but Poe preferred to decipher more complicated puzzles that involved multiple letters substituted for a single one or those requiring a secret keyword to break.

Poe wrote an article in 1840 titled “A Few Words on Secret Writing” and posted two puzzles to Graham’s Magazine, one of which was solved only in 1992, while the other was cracked in 2000. The ciphers were allegedly submitted by one W.B. Tyler, whom some suspect might have been Poe himself. It is also suggested that his more familiar works may contain unrecognized ciphers. Intriguing.[2]

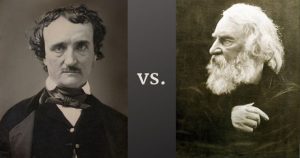

8 The Little Longfellow War

Poe was a struggling writer and editor of Graham’s Magazine in 1841 when he wrote a flattering request to the famous poet and professor of modern languages, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, for a contribution to his magazine’s pages. The Harvard academic couldn’t find time in his busy schedule and respectfully declined while paying Poe his own compliments. Longfellow’s graciousness nonetheless must have rubbed Poe the wrong way, and Poe began his scathing literary attacks on Longfellow.

Poe began with a negative review of Longfellow’s translation of a collection of poems, then proceeded to critique Longfellow’s own poems. Longfellow, Poe sneered, wrote “beautiful poems—by accident.” He dared accuse the professor of plagiarism, not in the sense of copying another’s words verbatim but appropriating his imagery, ideas, meters, and rhythms. Poe charged Longfellow with “the most barbarous class of literary robbery.”

The Little Longfellow War, as Poe dubbed it, escalated from there. While Longfellow himself didn’t deem Poe’s salvos worthy of a counter-salvo, he had many admirers who defended him. One of these, who went under the alias “Outis,” turned Poe’s definition of plagiarism back against him, pointing out that “The Raven” had 15 correspondences with an earlier poem, “The Bird and the Dream.” As expected, Poe launched a lengthy refutation, and the war dragged on for six weeks.

What motivated Poe’s tirades against Longfellow? Professional jealousy? Coming from a poor background and trying to make a mark as a poet, Poe may have felt some animus toward the moderately wealthy and successful Longfellow. Or the entire affair might have been a publicity stunt concocted by Poe, who loved playing pranks on the public. The mysterious Outis may have been none other than Poe himself.[3]

7 The Balloon Hoax

On April 13, 1844, the New York Sun blazed with the headline:

ASTOUNDING NEWS! BY EXPRESS VIA NORFOLK! THE ATLANTIC CROSSED IN THREE DAYS! SIGNAL TRIUMPH OF MR. MONCK MASON’S FLYING MACHINE!!!

It proceeded to detail how Irish adventurer Monck Mason, a real aeronaut who flew a balloon from Wales to Germany in 1836, conquered the Atlantic with a technically improved balloon that sailed from England to Charleston, South Carolina, in record time. “The air, as well as the earth and the ocean, has been subdued by science,” the Sun enthused. “God be praised! Who shall say that anything is impossible hereafter?” The Sun and the city newsboys made a killing selling the day’s editions to a public eager for more news. In an age of remarkable scientific breakthroughs, everything was indeed believable.

But not this story. A month later, Edgar Allan Poe admitted in an article that he was the source of the tale. Poe loved how people reacted to his hoaxes. His story of Hans Pfall’s journey to the moon was originally intended as a hoax, but he discontinued it when the Sun printed a story in 1835 of astronomer Sir John Herschel’s discovery of life on the moon, including bat-like creatures and unicorns. Richard Adams Locke, who concocted the story, was accused by Poe of plagiarizing Hans Pfall, and he may have devised the balloon hoax as revenge.

In the end, it was Poe who wound up being the loser. He had hoped to promote himself as a journalist, but his credibility was ruined. He never received any of the profits the Sun made. One thing was proven, though. Fake news sells.[4]

6 The Prototype for Sherlock Holmes

Poe invented the modern detective story. His sleuth, the brilliant amateur C. Auguste Dupin, provided the template for succeeding generations of literary detectives. That is to say, without Poe, we probably wouldn’t have Sherlock Holmes.

Dupin was modeled after Francois Eugene Vidocq, a former criminal who turned policeman and founded France’s Surete. Dupin is an eccentric gentleman of leisure with acute powers of analysis and deduction, which he uses to solve crimes. He smokes a pipe and has a nameless roommate who acts as his sidekick and narrator. Except for this friend’s anonymity, we might be reading a description of Holmes and his faithful Dr. Watson.

In the first Dupin adventure, “The Murders in the Rue Morgue,” Poe introduced the elements that would become the staple of classic detective fiction: the superhero armchair sleuth, the bumbling police force, the locked-room murder. The 19th century’s fascination with rational scientific reasoning and, at the same time, with darkness and the occult were merged by Poe into a new genre of fiction.[5]

5 The Myth of His Drug Addiction

“Respite—respite and nepenthe, from thy memories of Lenore;

Quaff, oh quaff, this kind nepenthe, and forget this lost Lenore!”

The protagonist in “The Raven” and other works by Poe are portrayed as taking drugs such as opium. It is natural to think that Poe must have been a drug user or, worse, an addict himself. His wild, fantastical tales must surely have been dreamed up by a drug-fueled brain. This is an unfortunate myth that smears Poe’s character. There is no evidence that Poe was an addict. It appears that neither was he a chronic alcoholic, for that matter, though he did binge drink occasionally.

Poe never spoke of a drug habit in any of his letters and personal documents. He claimed to have taken opium only once, in a suicide attempt after being rejected by a lady. It is not even certain if Poe was being truthful or being overly dramatic. Dr. Thomas Dunn English, who disliked Poe and had as much reason as his other detractors to speak ill of him, said after Poe’s death, “Had Poe a drug habit, I should, both as a physician and man of observation, have discovered it during our frequent visits to each other’s home and our meetings elsewhere. I saw no signs of it and believe the charge to be a baseless slander.”

The man responsible for the slander was Poe’s literary executor and biographer, Rufus Griswold. He hated Poe and never forgave him for giving a negative review of an anthology Griswold wrote. Griswold took every chance to ruin Poe’s reputation in his biography, from which succeeding generations sadly took their portrait of Poe the man.[6]

4 Solving the Murder of Mary Rogers

Mary Rogers was a vivacious and pretty teenager who worked in a cigar shop in New York. She was such a stunning beauty that men flocked to John Anderson’s shop to talk and flirt with her. In 1838, she disappeared suddenly, alarming her mother and most of the city. When she reappeared after two weeks, explaining that she had gone to visit relatives in Brooklyn, there was a collective sigh of relief. Some dismissed it as another of the Sun’s notorious hoaxes.

So there was little concern when Mary disappeared again on July 25, 1841. But three days later, the body of Mary Rogers was fished out of the Hudson near Hoboken, New Jersey. There were marks of violence on her body, and items of her clothing were later found in the woods by the riverbank. Initial suspicion focused on her lover, David Payne, but he had an airtight alibi. There was no shortage of suspects among the men who knew Mary. Or it may have been a random killing by a gang of criminals. Police were stumped by dead ends.

Edgar Allan Poe fictionalized the celebrated case, merely transferring the action to Paris and changing the names of people and places involved. Otherwise, all the details were accurate. In “The Mystery of Marie Roget,” C. Auguste Dupin analyzes the clues and, with the use of close reasoning, proposes to unmask the killer. But Poe leaves the solution hanging in the air. Dupin did have his own suppositions, but Poe just allows the story to fizzle out inconclusively.

After reading “Marie Roget,” some people thought that Poe knew too much. Did he know who the killer was—perhaps only too well? Poe had known Mary and was allegedly seen with her before her first disappearance. A man fitting Poe’s description was seen in Mary’s company three days before the murder. This was an author whose tales are obsessed with the deaths of young and beautiful women. Did Poe do the unthinkable? Marie Roget’s feeble ending simply means Poe was as baffled as the police were. The case still remains unsolved.[7]

3 Anticipating the Big Bang Theory

A year before his death, Poe published his most intriguing and visionary work, “Eureka,” with ideas so revolutionary it was banned in Czarist Russia. It is a prose poem on cosmology, where Poe opposes the contemporary concepts of a static, deterministic, and clockwork universe, which he felt was a dead-end for human imagination, intuition, and ultimately, self-determinism and free will.

Poe resisted the idea of fixed axioms as an artist relying on intuition, not as a scientist. But in doing so, he anticipated with remarkable prescience the scientific breakthroughs of the 20th century that would vindicate his ideas of an open and evolving universe.

The first to be inspired by Poe was Russian mathematician Alexander Friedmann, who published his equations for a dynamic universe in 1922, challenging Albert Einstein’s “cosmological constant.” Belgian priest Georges Lemaitre developed Poe’s idea that the cosmos began with a singularity (a “primordial particle”) with his Big Bang theory (Poe’s “one instantaneous flash”) in 1927. Not surprisingly, Einstein thought that Poe had a pathological personality.

Poe’s concepts of gravitation and electromagnetism give an elegant solution to the problem of dark matter and dark energy. He also discusses the unity of space and time, the equivalence of matter and energy, the velocity of light, black holes, and a pulsating universe. Truly, Poe gives us a practical demonstration of his belief that intuition can uncover the underlying reality of the cosmos.[8]

2 Death by Cooping?

On September 28, 1849, Poe arrived in Baltimore on his way from Richmond to New York. His movements for the next five days were unknown. On Election Day, October 3, he was found lying in the gutter outside Gunner’s Tavern, semi-conscious and wearing somebody else’s clothes. He drifted in and out of delirium for the next few days, calling out “Reynolds” repeatedly. Poe died on the 7th, muttering, “Lord, help my poor soul.” The official cause of death was phrenitis—swelling of the brain.

The mysterious circumstances surrounding Poe’s death invite numerous theories as to its actual cause: murder, alcohol, carbon monoxide poisoning, and rabies have been proposed. But one theory has gained traction—Poe was a victim of “cooping.” Cooping was a form of electoral fraud where victims were kidnapped, drugged, or forced to drink and made to vote several times for one candidate under multiple disguises.

The cooping theory explains Poe’s delirious state and why he was wearing clothes that were not his own. That he was found near Gunner’s Tavern, a polling place and hangout of cooping gangs, on Election Day was no coincidence. No one, however, has identified the mysterious “Reynolds.”

It is entirely fitting that the inventor of the detective story had a death that might have figured in one of his stories, a fascinating mystery left for us to untangle.[9]

1 Poe in the Afterlife

Mystery continued to surround Poe even after death. In 1863, psychic medium Elizabeth Dotten published “Poems from the Inner Life,” which she claimed Poe’s spirit dictated to her. “The influence of Poe,” she wrote, “was neither pleasant nor easy. I can only describe it as a species of mental intoxication.”

Needless to say, critics and skeptics dismiss her story. “The boundaries which divide Life from Death are at best shadowy and vague. Who shall say where the one ends and where the other begins?” Poe had written. So some believe Poe still haunts the earthly places where he once lived: his Baltimore home and his small cottage in the Bronx, New York.

But of more concern to historians than the whereabouts of Poe’s spirit is the whereabouts of his body. For 15 years, only a small sandstone block marked the poet’s grave. The citizens of Baltimore felt that Poe deserved more and raised funds for a new marker and had Poe, or what they thought were his remains, reburied beneath it.

It turned out that the plots in the area had been disturbed during some renovation work, and the reburied body apparently was not Poe’s. A sexton also remembered that the coffin it was in was also not Poe’s. Ensuing counter-claims further obfuscated the issue, and now we cannot be sure if Poe had indeed gotten the burial he deserved.

This didn’t stop a mysterious masked man in black from visiting the grave annually on Poe’s birthday from 1949 to 2009. He would come between midnight and 6 am to leave three red roses and a bottle of cognac on the site. The Toaster, as he came to be known, was never identified. But his actions had become a revered tradition, and the Maryland Historical Society decided to continue it with a new, but this time not-so-mysterious, Toaster.[10]

[ad_2]

Source link