[ad_1]

In my 30-odd years spent with American food artisans, I always wondered why vinegar—that dagger of acidity that can penetrate and transform any dish—didn’t get the same maker love as other pantry staples, like chocolate and coffee. And I wasn’t alone.

Rodrigo Vargas, now the founder of American Vinegar Works, also wondered why vinegar seemed stuck. “I am a traditionalist at heart and think that the best innovation can be as simple as doing something really well again,” he says.

Rodrigo Vargas [Photo: American Vinegar Works]

To establish there was a marketplace need for flavor-advanced, artisanal-made vinegar and determine how big it might be, Vargas, who went to Dartmouth and Columbia before working in strategic new product development for companies like American Express and Asurion, hired interns to help search out non-industrial vinegars in specialty shops and online resources, then mapped out product attributes: How were they positioning themselves? Were they leading with “raw and unfiltered,” or “Made in America”? Were the bottles plastic or glass with a premium look?

“Vinegar was the last part of the American pantry that had not improved, and it didn’t make sense,” he says. “I saw an opportunity to bring a slow fermented, fully flavored vinegar to American chefs and home cooks.”

But he still had no idea how to make it.

An innovation from 1823

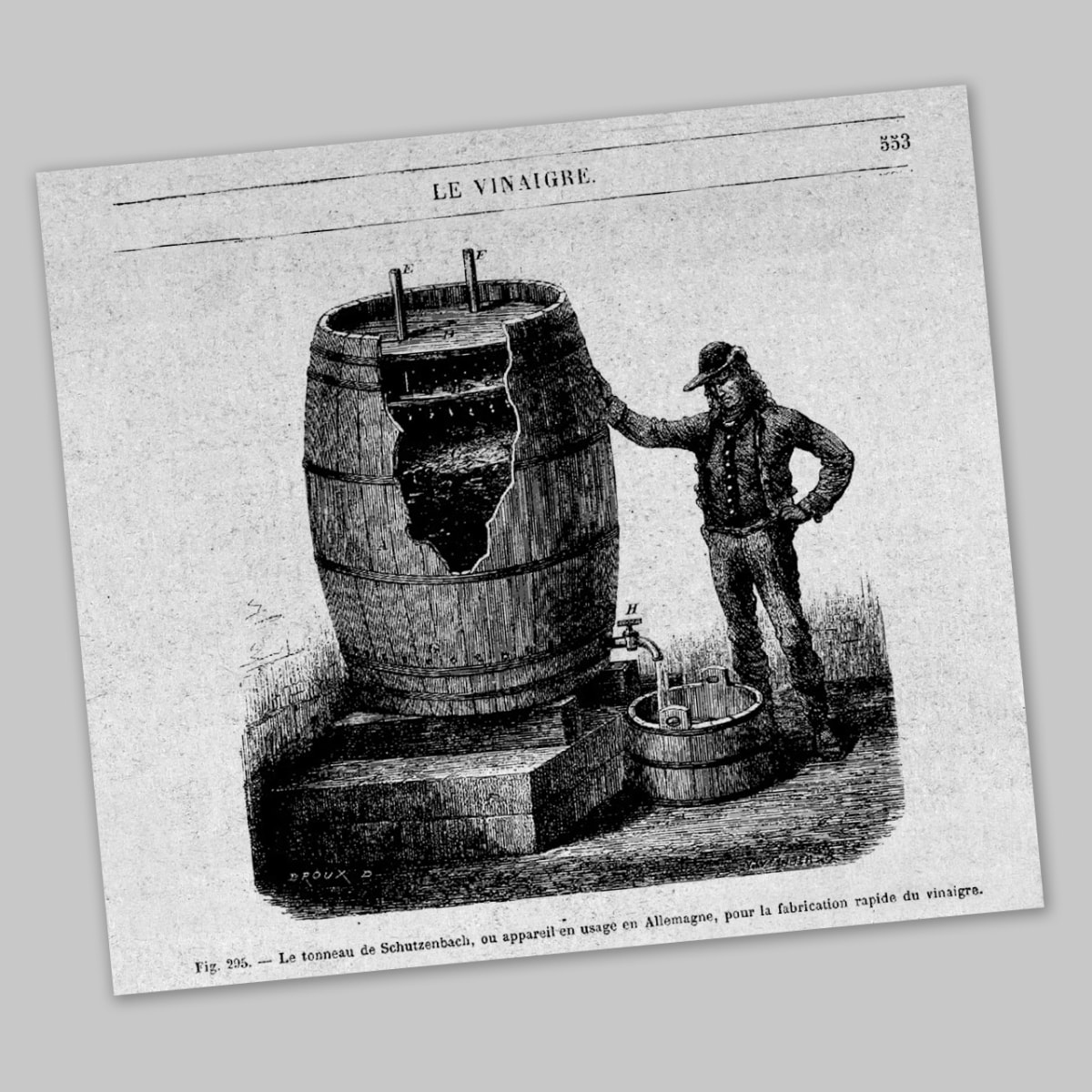

What followed was a world of research, with Vargas quickly realizing he could not compete on quantity or price of mass-produced vinegar, using methods that reduce fermentation from months to days. In exploring traditional methods, he came across an 1823 invention by a German scientist named Johan Sebastian Schutzenbach: “It was two chambered, drip-style machine that recirculated fermenting liquid to produce nuanced, complex flavored vinegar of extraordinary quality, well beyond the acid-forward commercial vinegars on most grocery store shelves today,” he says. “And it created the 19th-century’s golden age of vinegar.”

[Image: courtesy Bibliothèque nationale de France]

Unable to source an actual machine, long out of production in favor of faster cheaper methods, Vargas found a plate etching in “The Wonders of Industry” Encyclopedia (circa 1870s) within the collection of the National Library of France. With no technical training and not a lot of investment capital, he used the etching to construct a small mockup (acyclic storage boxes from The Container Store, hardware store tubing, fish tank pumps) that was not exactly food safe.

On the advice of a friend who worked in rocket science at MIT, Vargas took the model to Boston University’s welding shop, where rocket parts are constructed, and a simple replica in food grade stainless steel was assembled at a reasonable price.

[Photo: American Vinegar Works]

The developed equipment was rudimentary with operational problems Vargas didn’t anticipate, from clogged tubes to occasional vinegar floods caused by fluctuating temperature. “It was obvious that I would not be able to scale using those prototypes,” he says. “But at about $7,000 a machine, I could invest in enough to make the quantity and variety of vinegar needed to test marketability, and determine the next step of investment and production.”

[Photo: American Vinegar Works]

Rooted in place

Responding to continuing consumer interest in the human scale of artisanal products, Vargas distinguishes his vinegar with a “sense of place.” To get there, he relies on Massachusetts produced beer, cider, and mead—an example of place is the Cranberry Apple Cider Vinegar, cranberries being indigenous to that state and still its number one agricultural crop—as well as wine and Junmai sake from West-Coast-based resources, where local climate supports the growth of those ingredients. “The better the base alcohol, the better the vinegar, and what I make stands on the shoulders of America’s excellent wine and micro brewing cultures,” he says.

[Photo: American Vinegar Works]

In early 2020, after selling out his 480-gallon production at regional farmer’s markets, Vargas was ready to scale his business, investing in what it would take to produce enough vinegar to meet and move beyond current demand into the next sales segments of growth.

He relocated to the Whittall Mills complex in southern Worcester, Massachuetts, where rugs for the McKinley White House were once made, now a mixed-use building on the National Register of Historic Places. “The space felt right,” Vargas says. “We make vinegar with a 200-year-old method in a building from the same era.” Only now, with retro-tech equipment, renewably sourced electricity, and the mission of bringing era-relevant manufacturing back to New England, the heart of the American Industrial Revolution.

[Photo: American Vinegar Works]

The Maine difference

Equipment evolution took place at The University of Maine, one of the Northeast’s main educational food science departments, with a shop that did both welding and engineering. Explaining how the current prototype worked, the problems that occasionally arose, and what he wanted to achieve at the next level of production, Vargas went back and forth with the Maine team on solutions, ultimately resulting in a retro-tech double drip fermentation tank with built-in failsafe sensors including data capture recording the production run. Remote activation via Wifi provides Vargas and the Maine team with unrestricted access for precise temperature adjustments, eliminating flooding, and log analysis for incremental quality evaluation—how different variables at different points of the run affect taste.

Currently American Vinegar Works uses the retro-tech Maine machine aided by 11 of the original prototypes to make 15 varieties of vinegar, with number 16 launching in October, and two others already in aging barrels. With an annual production of about 12,000 gallons (a 25x increase) and room to continue expanding production, he plans to release several new varieties each year.

“Most industrial, commercial vinegars are made in about two days, while ours take at least six months, so we needed a little over a year to have enough production history to validate technique. Testing the advanced retro-tech prototype in 2022 gives us confidence to fuel growth in 2023,” Vargas says. “Fifty-seven percent of Americans already use vinegar, and our next job is to find our people.”

Francine Maroukian, a two-time James Beard Award winner, is a food and travel writer who also works as an operative researcher for C-suite executives in big retail.

[ad_2]

Source link