[ad_1]

This article is an on-site version of our Unhedged newsletter. Sign up here to get the newsletter sent straight to your inbox every weekday

Good morning. This week’s central bank meetings should hopefully give markets something new to chew on. Or not! Maybe it will all go as expected and nothing interesting will happen. Either way, this newsletter will march on. Email us: robert.armstrong@ft.com and ethan.wu@ft.com.

Will higher rates curb buybacks and send the market lower?

Our colleague Nick Megaw had a nice piece over the weekend on falling US share buybacks. The thrust of it was that between regional banks hoarding capital in the wake of the Silicon Valley Bank micro-crisis and higher interest rates, companies are buying back fewer of their shares. His chart:

Stock buybacks rise and fall cyclically, which is a persistent market irrationality (you would want companies to buy their shares back when the market is weak, and stocks are cheap; but they do the opposite). What is interesting about Megaw’s piece is that it suggests that if we are in a new, higher-rate regime, buybacks might be lower on a secular basis:

“Structural reasons as well as the interest rate environment are both contributors,” said Jill Carey Hall, equity and quant strategist at Bank of America. “We would expect buybacks to not be as big for the foreseeable future . . . When rates were zero it made sense for companies to issue long-dated, low-rate debt and use it to buy back shares. Now not so much.”

This issue is important because, for a long time, corporations have been the only consistent net buyer of US stocks. This Deutsche Bank chart from a few years ago tells the tale well (I will try to find or build an updated one in the coming days):

This is not a surprising result. Households (domestic and foreign) buy stocks when they need to invest, and sell them when they need to consume. It makes sense that over time there would be a rough match between their buying and selling (subject to demographic trends). Companies do an initial offering and then, as a general rule, avoid diluting investors with further issuance, while doing buybacks when they can.

If the dominant net buyer of stocks is set to back off because of higher debt costs, a negative impact on prices seems to make sense. That is, there might be a direct causal channel linking higher interest rates and lower stock prices.

Consider a company with a price/earnings multiple of 20 and a tax rate of 20 per cent, which can borrow medium-term money at 2.5 per cent, as a triple-B-rated company probably could have two years ago. An entirely debt-financed buyback of 5 per cent of this company’s shares outstanding would be over 3 per cent accretive to its earnings per share. At a 6 per cent cost of debt, which a triple-B company might pay today, such a buyback would be dilutive to EPS (EPS accretiveness, I should emphasise, is hardly the final word on whether a buyback is a good idea, but it is a relevant consideration and is satisfyingly quantifiable).

But the fact that rates affect the economics of debt-financed buybacks does not, in itself, imply that at dramatically higher rates, dramatically fewer buybacks will be done. The sensitivity of buyback decisions to economic reality, and the proportion of buybacks that are financed with debt, could both have a mitigating influence.

On the first point, while it is hard to see why a company would do a buyback that was not accretive to earnings per share at all (except, perhaps, to offset dilution from stock compensation), we know that buybacks are at least somewhat insensitive to economic reality because we know they are procyclical. More buybacks get done when stocks are more expensive. Companies are not perfectly economically rational about buybacks, so the impact of higher debt costs on buybacks might be less than one would expect.

On the second point, it is important to note that a lot of buybacks are done by companies that generate so much cash that debt costs are irrelevant. In the last quarter, Microsoft, Apple, Alphabet, Exxon and Chevron — massive cash spinners all — accounted for more than a quarter of all the buybacks in the S&P 500, according to data from S&P Dow Jones Indices.

Overall, I think we should temper our fears about higher rates dragging down the market by discouraging buybacks. But to the degree to which you think buybacks support stock prices — and there is a debate to be had about this — it may be that higher rates will further divide the market into haves and have-nots. The cash-rich haves will be able to sustain their buybacks, and potentially their share prices, and while the have-nots who have depended on debt financing will have to give them up.

Labour market normalisation

If the economy does land softly, will we know it when it happens? Has it happened already? Growth has clearly held up; on inflation, though, it is harder to say. Core inflation measures are lagged. Some already argue that, after accounting for the slow pass-through of market rents to the official indices, inflation is currently verging on 2 per cent and we are in a soft landing. We just can’t see it yet.

If inflation is too slow a gauge, the next place to look is the labour market. When labour demand outruns supply, it irritates the Fed, keeping it focused on supposedly labour-sensitive inflation data like non-housing core services, which picked up in August. With monthly payroll growth below 200,000 and unemployment ticking up, everyone agrees the labour market has cooled off. The question is how much.

In two recent notes, Goldman Sachs economists argue that we’re basically back to normal. Labour market rebalancing is “now largely complete”, with many measures of tightness back to pre-pandemic levels (the red line below takes the average):

(The “labour market differential” is the number of people telling the Conference Board jobs are plentiful minus those saying they’re hard to get. The “jobs-workers gap” is employment + job openings — labour force, using Goldman’s estimate of job openings.)

The lingering worry is wage growth, which is still far from normalising. You can make the case, as Goldman does, that it is just a matter of time before wage growth falls. In theory, a decline in labour market tightness — which is to say worker bargaining power — should happen before wage growth slows. One of the strongest measures of tightness, the quits rate, tends to lead changes in wage growth, as the chart below shows (look, for example, at the mid-2010s):

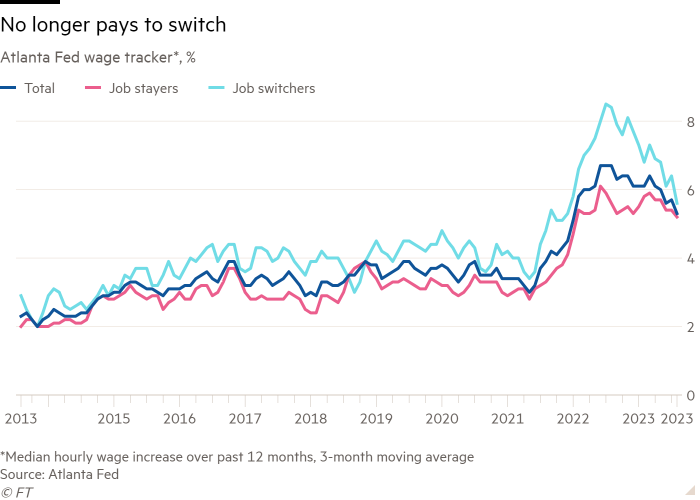

All clear, then? In his latest edition of The Overshoot, Matt Klein points out an important subtlety. Much of the wage disinflation we have seen so far is coming from a reversal in the additional gains enjoyed by job switchers — people who have gotten raises by finding new jobs — since the pandemic. Data from the Atlanta Fed’s wage tracker indicates switchers are now getting raises in line with stayers. Stayers’ pay increases, meanwhile, are stubbornly high (pink line below):

One observation that might square Klein’s point with Goldman’s is that when we talk about the labour market normalising to 2019 levels, it’s less often noted that the 2019 labour market was very strong. Yes, inflation was at 2 per cent back then, but there could well be a difference in wage-price dynamics once inflation is already high. Returning to 2019 may be necessary, but not sufficient, to bring inflation down. Until wage growth falls, declaring a soft landing strikes us as premature. (Ethan Wu)

One good read

“Which of you shall we say doth love us most/That we our largest bounty may extend/Where nature doth with merit challenge?”

FT Unhedged podcast

Can’t get enough of Unhedged? Listen to our new podcast, hosted by Ethan Wu and Katie Martin, for a 15-minute dive into the latest markets news and financial headlines, twice a week. Catch up on past editions of the newsletter here.

Recommended newsletters for you

[ad_2]

Source link