[ad_1]

The Wild West was a weird place. We kind of hope you should know that by now, after all. That’s because we’ve covered this topic before! You may recall an earlier deep dive into some very strange and unexpected facts from the days of the Old West.

And now, well, we’re back for more. In this list, we’ll go through another ten bizarre facts and crazy stories about life on the frontier. As Americans were pushing westward to expand the Union, lay claim to new territories, and build a transcontinental railroad system, strange stuff was happening all around.

Don’t believe us? Well, read on, then! These ten tales cover some surprising and unlikely stories from one of the wildest and weirdest times in American history!

Related: Ten Strange Things You Never Knew about the Wild West

10 The Case of the Traveling Corpse

Wannabe outlaw Elmer McCurdy robbed a passenger train in Oklahoma in 1911. He thought the train was transporting thousands of dollars for banks in the state, and he could get away with a nice amount of loot. Unfortunately for him, the train had no bank bullion. Even worse, McCurdy got away with just $46 in total from the robbery. And as if that wasn’t bad enough, Oklahoma lawmen shot him to death shortly after tracking him down days later. But all that is the normal part of this story—things only started getting weird after McCurdy was killed by fed-up law enforcement officers.

First, McCurdy’s corpse was embalmed with a standard arsenic preparation. Then, it was sold to a traveling carnival. The carnies wanted to make some money off McCurdy’s reputation as an outlaw, so they traveled with the body and displayed it at fairs as a sideshow. For six decades (!!!), McCurdy’s body was bought, sold, and bought again by various county fair outfits roaming across the Midwest. Haunted houses and wax museums even got in on the market, too, with the late outlaw’s corpse changing hands over to some of them too.

After more than sixty years on the move—and having brought in way more money than he ever stole while alive—the long-dead McCurdy wound up in an amusement park funhouse in Long Beach, California. The year was 1976, and television producers had come to the park to film scenes for The Six Million Dollar Man. During filming, with McCurdy’s body being used as a prop, a finger (or, by some accounts, an entire arm) fell off.

The Los Angeles County Coroner’s Office cried foul and had the body tested to confirm its provenance. Sure enough, it was that of McCurdy, who had died more than 65 years before in Oklahoma. Finally, good sense prevailed this time around. McCurdy’s corpse was mercifully returned to the now-not-so-Wild West, and he was buried at long last in the famous Boot Hill Cemetery in Dodge City, Kansas.[1]

9 The Southpaw Puzzle

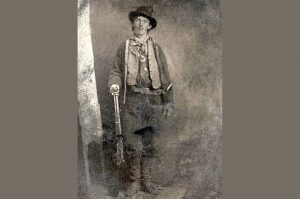

For a long time, historians and Wild West amateur aficionados alike figured Billy the Kid was left handed. That’s because of one famous photograph: a tintype photo from his youth in which the outlaw can be seen with a gun belt on his left side and a Winchester Model 1873 lever-action rifle close by. Seeing the gun belt on his left and his right hand holding the barrel of the rifle—leaving his left to theoretically pull the trigger—led to the understandable assumption that Billy the Kid (real name: William Bonney) was a southpaw. Which, while not the most important thing about his controversial life, would at least be interesting, right? There sure aren’t nearly as many southpaws around, then or now!

But actually, the reality is probably far different than that. For one, tintype photographs like that were made by producing a negative image that was then developed in reverse to appear positive. Thus, the final finished photo was a 180-degree horizontal rotation from what was snapped. And thus, Billy the Kid’s gun belt would almost certainly be on his right side, not his left. And the rifle he’s holding would almost certainly be set up so he could pull the trigger with his right hand, not his left.

Plus, there’s more! That specific model of Winchester rifle features a loading gate on the right side. It looks as though it’s on the left based on the picture—but again, the tintype being flipped would lead to that incorrect assumption. In reality, Winchester only made right-facing loading gates for the 1873 lever-action rifle. And thus, right-hand-dominant people would have had a better time using them.

Now, is it possible Billy the Kid really was left handed but had to adapt to right-hand-focused guns in Old West society? Of course! But the picture many point to as “proof” of his left-handedness isn’t as cut-and-dry as you may have thought. And now you know![2]

8 Gold Rush Reruns

It’s awfully tempting to think that the frontier practically invented the gold rush. After all, one of the most commonly cited events in the Old West is the 1848–1849 California Gold Rush. When James Marshall struck it rich at Sutter’s Mill in Northern California, it seemed as though the entire world rushed out west to lay claim to their own fortunes in that territory. Other western gold rushes only added to the lore, too. Colorado saw a major gold rush throughout the second half of the 19th century. And Nevada’s infamous Comstock Lode was a silver push unlike few others the world had seen before.

But all that was preceded by far earlier eastern gold rushes that were just as popular in their own heyday. The first major American gold rush took place in Cabarrus County, North Carolina, way back in 1799. A young boy named Conrad Reed found a large yellow rock on his father’s farm northeast of present-day Charlotte. The family kept it as a doorstop for years before a visiting jeweler recognized it for what it was: a 17-pound (7.7-kilogram) hunk of gold! From there, the rush was on. The Reed family and pals dug up all the land they could handle in the region, and other gold rushers swarmed in to look for their own fortunes as well.

Then, two decades later, another major gold rush occurred in northern Georgia, just a few hundred miles from the Reed family farm. That, too, brought fortune seekers from far away. They clashed with Native American tribes and each other while trying to fight for whatever valuable metals they could dig up. All that is to say this: The frontier was far from the first scene of the gold-rush frenzy in the United States. While California’s “49ers,” as they came to be called, may be the best well-known, they certainly weren’t the first. Far from it![3]

7 The Shockingly Brief Gunfight

You can’t learn too much about the Wild West before learning about the “Gunfight at the OK Corral.” The name itself is memorable, for one. And the story of those who fought on that fateful Arizona day in 1881 has stayed in the public’s minds through the ages. On one side, it was the Earp brothers—Morgan, Virgil, and Wyatt—along with Doc Holliday. Fighting against those lawmen were outlaws and scofflaws Billy Claireborne, Billy Clanton, his brother Ike Clanton, and the two McLaury brothers, Frank and Tom. When the dust settled, both of the McLaury boys and Billy Clanton had been killed. On the good guys’ side, Virgil and Morgan Earp had both been wounded but survived.

But that’s just the thing: There was a very, very short time between when the first shot rang out and that aforementioned dust actually settled. Thirty seconds, in fact! Despite involving nine men and a hail of bullets, the entire gunfight lasted less than half a minute. While movies may make it seem like Old West gun battles are long, drawn-out affairs with men hunkering down behind wooden barrels and hiding behind walls, this one wasn’t that. In just beyond the blink of an eye, the West’s most infamous battle began and ended.

Oh, and that’s the other crazy part: The gunfight wasn’t actually at the OK Corral, either. If we’re being technical here (and of course we are!), the shootout actually took place on what is the present-day intersection of Third Street and Fremont Street in the city of Tombstone. That is technically out on the public road behind the corral itself, not within or as part of its area. So even what we call the shootout itself is a bit of a misnomer![4]

6 The Real-Life TV Saloon

Did you ever watch the old TV show Gunsmoke? If you did, you certainly know about Miss Kitty’s Long Branch Saloon. Said to be set in the outlaw town of Dodge City, Kansas, the saloon was a staple in the iconic and still-memorable television show about frontier life. But what if we told you that the saloon really did exist? And, in fact, it still exists… sort of.

Miss Kitty’s Long Branch Saloon was an actual establishment in which Dodge City locals and those passing through could grab a drink—or two, or three, or four. It actually has such a long history in the town that nobody knows quite when it was first established. But they do know without a doubt that the original saloon burned down in the Kansas frontier town’s infamous Front Street Fire of 1885. That blaze knocked out a ton of local businesses in the growing city, forcing some to shut down for good and others to rebuild atop the ashes.

Years later, the saloon was resurrected. It was never quite the same as it was when Dodge City was still an outlaw town. And in the modern age, it still exists too. But now, its purpose is far more as a place where Gunsmoke fans can go and re-live some memories from their television-watching youth than anything to do with the actual 19th-century original saloon itself.

Still, according to Kansas historians and regional museums, the original Miss Kitty’s sounded like a wild hotspot for the day. It was said to serve milk, tea, and lemonade—which is nice, we suppose. And it also offered up sasparilla, beer, and all kinds of alcohol. Okay, now we’re talking! So basically, if you’re ever in southwestern Kansas, you know where to turn for a taste of the Old West![5]

5 The Old (Old, Old) West

Obviously, Native American settlements predate European ones in America by thousands and thousands of years. There’s no question about that. Or at least there shouldn’t be. Because while Jamestown may have been the first settlement of European immigrants to North America when more than 100 settlers showed up in 1607, it wasn’t the first permanent settlement in what is now the United States. Not by a long, long, long shot, in fact!

Historians now know that the Acoma Pueblo, just west of what is now Albuquerque, New Mexico, predates the Jamestown settlement by at least 500 years. Of course, no Europeans knew about the Acoma Pueblo until much, much later, when the Spanish conquistadors and missionaries came through. But it was there all the same, even if white settlers never knew where to look for it.

The Acoma Pueblo was quite the setup when it was really rolling too. The Acoma called it their “Sky City” settlement. It had a permanent population of about 5,000 people. It sat on the very top of a 300-foot (91.4-meter) tall mesa, too, so it was naturally fortified. That advantage allowed the Acoma Pueblo to become a cultural center. Other Native groups would come from miles around to trade goods and interact with the powerful Acoma people.

Today, the site remains a cultural center and historic heritage complex. The area allows Americans to learn all about the very first settled civilization with its current-day borders. And to be technical, its history far predates anything in the Old West—and anything in all the United States![6]

4 The First (Phony) Film Cowboy

If you know anything about the history of old western films, you have probably heard the name Broncho Billy Anderson. He was a cowboy who starred in 1903’s silent film The Great Train Robbery. But the reality of Anderson’s real life away from the screen was very different than what you might expect of America’s first cowboy star of the moving picture era.

In reality, “Anderson” was an Arkansas native born Maxwell Henry Aronson in 1880. He was the son of a traveling salesman who made his money journeying all over the Ozarks to sell products to local families and dry goods stores. Maxwell didn’t want that for himself, though. So when he was just a teenager, he fled home for New York City. Once there, he caught on with the budding film industry and started producing silent movies. In his career, he wound up producing and acting in literally hundreds of them. So in that way, he was one of America’s first movie stars.

But he wasn’t a cowboy. He’d never been a cowboy, had never been out west for any long period of time, and had no history with any part of the Wild West. He merely acted as the inauthentic Broncho Billy Anderson in 1903’s iconic movie, and the legend took on a life of its own from there. The skeptical among us might say he was the first of a long line of phony Hollywood stars with made-up backstories meant to sell to a movie-hungry public. Regardless, Aronson certainly wasn’t the last![7]

3 The Double-Buried Jesse James

No, we don’t mean the double-barreled Jesse James—although he was certainly that during his hectic early years, too. Instead, this has to do with what happened after his death. After James’s notorious early days robbing banks and causing mayhem all over the West, he mostly settled down at his homestead in Kearney, Missouri. There was just one problem with that: All the enemies he made during his early life were violent guys with long, long memories. So after trying to lay low for a while, he was outed by a former foe and murdered in 1882.

At first, James’s body was buried in the front yard of his farm plot in Kearney. His family did this because his legend made it so that they were worried trophy hunters might rob his grave. That didn’t happen, and James’s body rested there for a while. Then, years later, his body was exhumed and reburied in a more permanent plot in Mount Olivet Cemetery in the small Missouri town. But that’s not where this story ends, unbelievably.

Years and years and years after the West was won—in 1948, to be exact—a man came forward claiming that he was the “real” Jesse James. A court even let him legally adopt the long-dead bandit’s name. In reality, the man was a 101-year-old named J. Frank Dalton, and the Jesse James story was totally made-up. That didn’t matter much when Dalton died and was buried down in Granbury, Texas, though. The locals in Granbury bought Dalton’s claims hook, line, and sinker, celebrating his death and burial there with a tourist attraction befitting an old outlaw.

The controversy got so hot regarding James’s double burial sites that DNA came into play decades later. Scientists exhumed Kearney’s James, confirmed via mitochondrial samples that he was the real James, and discarded Dalton’s claims. The myth had lived long enough to eclipse fact, though, and so Granbury is still known by many as the burial spot of Jesse James—even though it isn’t. Oops![8]

2 Cowboy Hats Weren’t Cowboy Hats

Working outside under the harsh sun meant pioneers pretty much had to wear hats—and they almost always did. But they didn’t wear the ten-gallon cowboy hats that we think of today when we look back on the Old West. Those hats were only made famous in the 1920s and later. And they were only really popularized because of Hollywood’s depiction of cowboys in the movies. The classic, oversized cowboy hats weren’t anything a real cowboy would have worn across the western half of America in the 19th century!

Instead, “real” cowboys of that era chose to wear a smaller, flat-brimmed Stetson hat that was commonly called the “Boss of the Plains.” Menswear designer John Stetson himself came up with these authentic cowboy hats in that era after he saw what was previously being worn by pioneers. Early settlers wore straw, silk, fur, and even wool hats. They were horrible in all conditions: too hot in the summer and too cold in the winter. Worse, they absorbed rainwater and stayed soaked for hours after.

So Stetson created the aforementioned “Boss of the Plains.” It was deep with a flat, smaller brim. The entire hat was made out of nutria fur and completely waterproof. And the brim was curled at the ends to shed rainwater easily. Plus, the hat could be flipped over and used as an impromptu water bucket for a horse in need—a critical trait to have for many of the cowboys traveling tough trails.

If you’re curious about the cost, Stetson’s new creation ran right around $5 in most dry goods stores at the time. That’s more than $75 in modern money—so it wasn’t a cheap purchase for men who may not make a ton of money for a year of hard, unforgiving labor. But it was a high-quality product that lasted a very long time, so cowboys were willing to shell out the money to get a little break from the sun and rain.[9]

1 The West Had Real Gun Control

It’s easy to think that the Wild West was a free-for-all when it came to guns. After all, the great and crazy stories from the era all center on outlaws packing pistols and aiming rifles. Shootouts, bandits, highway robberies, daring train takedowns—you name it, and the West had it. And guns were at the center of it all, right? Lead was mightier than the sword (and the pen, if we’re being honest).

But in reality, the West had gun control like you wouldn’t believe. In some ways, it was far more stringent than what we know today. Way back then, frontier towns from Deadwood and Dodge City to Abilene, Garden City, and even Tombstone required you to hand in your guns when you entered the city limits. Literally! The rules at the time in most of those locales forced visitors to go down to the local sheriff’s office and hand in their guns upon entering the town. Then, the sheriff would hand them a token that represented the guns they were (temporarily) giving up. So, in that way, the Wild West had the world’s first coat check—for firearms.

Now, there was one exception to some of that strict gun control: locals. If you were a known resident of a town and had a relationship with the sheriff, it was customary that you’d be allowed to keep your guns with you at home. Basically, after years of outlaw behavior and outright banditry, sheriffs wanted unknown visitors to be unarmed as they made their way through town. Known entities could stay armed for domestic use and family safety. But overall, gun control on the frontier was much tighter than you might imagine![10]

[ad_2]

Source link