[ad_1]

School shootings and acts of domestic terrorism have become too common today. Since the Columbine High School massacre in 1999, there have been 386 school shootings, and in 2022, there were more school shootings than in any other year since 1999, with forty-six total. Unfortunately, there have been more shootings with more victims in the first three months of 2023 than in the same period last year, so 2023 may exceed the record.

Many of these horrible offenses are well known, such as what occurred at Columbine High School on April 20, 1999, in Littleton, Colorado. That morning, during the second period, two 12th-grade students, Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold, entered the school with several firearms and homemade explosives and opened fire on their classmates. Twenty-one people were injured, and fifteen were killed, including the two shooters, after they turned the guns on themselves.

The tragedy at Columbine was said to be the worst school disaster at the time and is still considered one of the deadliest. However, less commonly known is the Bath School Disaster, which remains the deadliest act of school violence in the United States.

On May 18, 1927, a series of violent attacks were carried out by 55-year-old school board treasurer Andrew Kehoe. At the time, all schools in the town were consolidated into one building, which brought all the region’s students to one location, which 236 students attended. The attacks killed thirty-eight elementary school children and six adults and injured at least fifty-eight others.

Below are ten disturbing facts about the Bath School Disaster.

Related: 10 People Who Survived Multiple Disasters and Deadly Situations

10 Kehoe Was Upset about a Rise in Taxes

The village of Bath is located about 10 miles (16 kilometers) northeast of Lansing and was an average Michigan agriculture community in the 1920s. Like many schools at the time, the town had a one-room building for students of all ages, sharing one teacher. However, in 1922, the township voted to create a consolidated school district and build a new school funded by increased property taxes. With such a small community, it was an expansive endeavor. The school opened that November and welcomed 236 students of various ages.

In 1923, the district purchased five acres (2 hectares) for an athletic field, paid for two lighting plants, and paid interest on $8,000 on the principal, which left the township bonded for $35,000 on the school. At the time, the resident’s school taxes were $12.26 per thousand valuations, but by 1926, it had gone up to $19.80 per thousand.

After the consolidation, Kehoe was enraged because of the tax increase, which resulted in him owing $10,000 in taxes on his buildings and his remaining eighty acres (32.4 hectares) of land. His anger led him to become a member of the school board, and in July 1924, he was appointed the treasurer. He fought to decrease school costs and clashed with other board members, especially if they didn’t see things his way. It is said that he despised the school superintendent, Mr. Emory Huyck.

In 1925, the death of the township clerk left an opening for the position, and Kehoe took up the role. The following year, he ran for the position but was defeated because of his reputation on the school board. Around the same time, he pleaded his case to the township about why they should cut the valuation on his farm and tried to convince the mortgage holder he had paid too much money to them.[1]

9 The Massacre Started at His Farm

After losing his position as the township clerk, Kehoe was angered. Shortly after, it was found that he had ceased working on his farm altogether and had stopped making payments on his insurance and mortgage.

It was later discovered that Kehoe had cut his wire fences and put dynamite on the tractor in his shed to release his animals as part of his preparation to destroy his farm. He also gathered lumber and other materials in his shed.

On May 16, 1927, Kehoe’s wife, Nellie, was ill with tuberculosis and released from Lansing’s St. Lawrence Hospital. Sadly, she was murdered by her husband sometime between her release and the bombings two days later. She was found in a wheelbarrow near the chicken coop with her skull crushed, where her body burned after the explosions and fire. Throughout the house and farm buildings, Kehoe placed and wired homemade pyrotol firebombs.

On the day of the bombing, at 8:45 am, Kehoe detonated the bombs on his farm and in his house. Neighbors noticed the fire and rushed to the scene to help. The neighbor, O.H. Bush, and several other men crawled through a window to look for survivors but found nobody in the house. As they tried to salvage some belongings, Bush noticed dynamite in the corner of the living room.

As Kehoe was leaving his property in his truck, he stopped to tell the volunteers that they should get to the school and took off.[2]

8 The Explosives Used Were Purchased Legally

While investigating the tragic events of the Bath School disaster, authorities learned of Kehoe’s activity at the school and frequent purchases of explosives. They concluded that his plan had been underway for at least one year. During the winter of 1926, Kehoe was asked to perform some repairs inside the school building, as he was regarded as a handyman and familiar with electrical equipment. Because of this, he was granted access to the building without raising suspicion.

Earlier that year, at the beginning of the summer, Kehoe purchased a ton of pyrotol, which farmers often used for excavation. Months later, in November, he traveled to Lansing to purchase two boxes of dynamite from a sporting goods store. Farmers also commonly used dynamite, so he was able to buy it legally. That December, he purchased a .30 caliber Winchester bolt-action rifle.

Kehoe purchased small amounts of dynamite and pyrotol at different stores on different dates to avoid suspicion. Over the course of several months, Kehoe made random trips to the school, bringing explosives with him and concealing them within.[3]

7 Only a Third of the Explosives Went Off

Neighbors believed Kehoe had been working on his plans for several months. David Harte, who lived across the street, had said that Kehoe had been busy for at least 10 days stringing wires together. He studied electrical engineering when he attended Michigan State University and got a job working as an electrician in St. Louis after.

The morning of May 18, at about 8:45 am, just after the farm explosions, the dynamite that Kehoe had planted exploded in the north wing of the school, killing 38 people. It was found rigged with an alarm clock that had been used to detonate at a scheduled time, but thankfully, most of the explosives failed to ignite.

Police later found a short circuit in the wiring which stopped more explosives from detonating and the attack from being worse. Over 500 more pounds of dynamite remained in the south wing of the school unexploded. In another part of the building’s basement, officers found a gasoline container fitted so that the expansion of the gas would force the vapor through the tube to a spark gap where it could have exploded.

Police stated that the dynamite was wired so perfectly that they couldn’t believe that Kehoe worked alone. The electrical wiring that led to the dynamite and powder charges planted throughout the school was so well done that it was hard to believe one person accomplished the task. Also, enough unexploded dynamite and powder were found to fill a small truck.[4]

6 Kehoe Targeted the Superintendent

People in the small, rural community started to rush to the school to help, and parents gathered looking for their children. While locals worked on rescue and recovery at the school, Kehoe drove to the schoolhouse in his truck. Prior to the attack, Kehoe had filled his truck with dynamite and metal debris capable of producing shrapnel during an explosion.

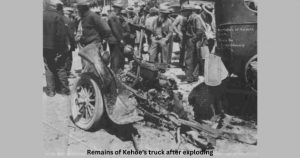

He pulled up to the school 30 minutes after the first explosion, where he saw the 32-year-old Superintendent Emory Huyck. Before arriving at the school, Kehoe had circled the village when he discovered that Huyck had survived the blast and was assisting with rescue efforts. Kehoe was vocal about his dislike toward Huyck because he advocated for the consolidation of the school, whereas Kehoe opposed it. He summoned Huyck over to his truck, and as soon as he was close, Kehoe fired his rifle into the backseat, causing another explosion. The truck blew up, and shrapnel burst in every direction.

The truck explosion killed Kehoe, Superintendent Huyck, two other adults, and a child who had escaped the school bombing.[5]

5 One-Fourth of the Town’s Children Were Killed

Bath was a rural community with a population of about 300 at the time of the disaster. The north wing, where the explosion occurred, was the elementary area of the school, and its destruction claimed the lives of 44 people, with 38 of them being elementary-aged children. This great loss took away one-fourth of the town’s children. Another 58 people were injured.

Some families lost multiple children in the attack. The children who lost their lives were between 8 and 13 years old and were in grades second thru sixth. One student, 10-year-old Beatrice Gibbs, passed away three weeks after the attack due to injuries, while another was killed when Kehoe caused his truck to explode. But the rest were killed by the initial explosion or buried in the rubble of the building.

Also killed in the disaster were two teachers, a retired farmer, a postmaster, the superintendent, Kehoe’s wife, Nellie, and Kehoe himself. There is a plaque in Bath that lists all 45 victims killed in the Bath School massacre, apart from Andrew Kehoe.[6]

4 Kehoe Left Chilling Words on a Sign at His Farm

Kehoe took the time to destroy his farm and house, which had been his wife’s childhood home, before the attack on the school. The couple purchased the property in 1919 after the death of Nellie’s uncle, and it was considered one of the nicest homes in the area. They were paying off a $6,000 mortgage to the uncle’s estate. When Kehoe stopped making his payments, it created a lot of tension among the relatives.

It was also discovered that he had girdled the shade trees to kill them and cut through his grape vines only to return them to their place so they looked untouched. Kehoe had let all his animals loose except for two horses in the barn, tied up, with their feet bound together with wire so they couldn’t escape. They were also found burned to death.

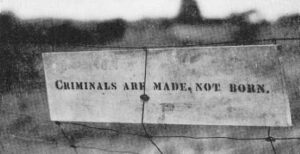

When police found Nellie’s body placed in a wheelbarrow inside the chicken coop, it was heavily charred from the explosions and fire. Around the cart, he had piled silverware and a metal cash box with money inside. At the far end of the farm, they found a wooden sign wired to a fence where Kehoe’s final message was written, “Criminals are made, not born.”[7]

3 Kehoe’s Stepmother Died Under Suspicious Circumstances

Andrew P. Kehoe was born on February 1, 1872, in Tecumseh, Michigan, and had 12 siblings. He graduated high school and began attending Michigan State College, where he studied electrical engineering. He later moved to St. Louis, where he worked as an electrician.

After the death of his mother, Kehoe’s father, Philip, married a widow much younger than him. Soon after, they had a daughter. It was said that Kehoe and his stepmother fought often.

On September 17, 1911, his stepmother was attempting to light the family’s oil stove when it exploded and set her on fire. Kehoe, who was 14 years old at the time, watched her burn for a few minutes before throwing a bucket of water on her. However, the fire was oil-based, which only made the flames spread faster. Her body was engulfed in flames when rescuers made it to the scene. The fire was put out, and she was taken to the hospital, where she died of her injuries a week later.

The stove’s malfunction was left unresolved, and Kehoe was never charged with wrongdoing. Still, many were suspicious and believed that he had caused the fire.[8]

2 Kehoe’s Body Was Buried in an Unmarked Grave

As hundreds of people worked at the wreckage site to find and rescue children pinned beneath the rubble, operations were set up at a local drugstore, Crum Drugstore, where aid and comfort were provided for victims and their families. Bodies of the deceased were taken to the town hall, which had temporarily been turned into a morgue.

The Red Cross managed donations sent to pay for medical expenses and the burial costs of the deceased. Multiple funerals were held throughout the next few days, with as many as 18 being held that Saturday, May 22. Most children were buried in the local cemetery and can still be found there today.

Family took Nellie Kehoe’s body, and she was buried in Mount Hope Cemetery in Lansing, Michigan, under her maiden name. Kehoe’s body was eventually claimed by his sister and buried in an unmarked grave and unnamed cemetery. It was later revealed that he was buried in the paupers’ section of Mt. Rest Cemetery in Clinton County, but his grave is still unmarked.[9]

1 A Historic Event Overshadowed the Disaster at Bath

The Bath School Disaster made national headlines but quickly disappeared. One reason media outlets stopped covering the story is that Kehoe did not fit most people’s ideas about terrorists. Also, because Kehoe had killed himself, the case was closed, and there would be no sensational trial or execution to draw the public back into the story.

In large part, the attack on the school was overshadowed in the media because American aviator Charles Lindbergh crossed the Atlantic on the first solo transatlantic flight just three days after the disaster. On May 20-12, 1927, Lindbergh made a nonstop flight from New York City to Paris, all 3,600 miles, and did so alone for 33.5 hours. Not only was it the first solo mission, but it was also the longest at the time by 2,000 miles. Lindbergh’s achievement spurred global interest as he won many awards, was promoted in the U.S. Army Air Corps Reserve, and even became Time magazine’s first man of the year.[10]

[ad_2]

Source link