[ad_1]

“This completes the transition to Apple silicon,” Senior Vice President of Hardware Engineering John Ternus noted during last week’s WWDC keynote. Apple never promised the process would happen overnight.

At the 2020 event, CEO Tim Cook promised a two-year transitionary period. The company missed the deadline by a year, but a lot has happened during that time, not the least of which was a global supply chain grounding to a halt. That’ll adjust a timeline or two.

Apple officially crossed the finish line with the arrival of the Mac Pro, which has long been something of an odd duck in the line. Issues with the “trash can” model caused a complete internal rethink. The lovingly designed “cheese grater” arrived at the end of 2019, with a starting price of $6,000. Halfway through the following year, however, everything changed.

The long-awaited arrival of Apple silicon represented a fundamental shift for the entire line. Suddenly the lowest-end Macs were putting up truly impressive numbers. In March of last year, a new contender emerged. The Mac Studio slotted at the top of the line, replacing the short-lived iMac Pro and, seemingly, the Mac Pro.

More than anything, the system resembles a grownup Mac Mini, ditching the iMac’s all-in-one design for a more classic PC/monitor setup. Apple also marked the occasion with the introduction of a Studio Display at $1,599. The model I tested last March featured an M2 Max chip. It blew the rest of our benchmarked Mac systems out of the water, and it wasn’t even top of the line.

As Matthew noted in his piece on the executive decision-making that led to the new desktop’s creation, “The Mac Studio as configured will set you back around $3,200. Only around $20,000 cheaper than the Mac Pro I used to perform this test back in 2020.” The system’s arrival felt like Apple rekindling its love for creative pros – a connection that had grown a bit shaky in previous years.

You’d be forgiven for assuming that was the nail in the Mac Pro’s coffin. Ultimately, however, the company has gone back to the well. As for the why, we can answer that in one word: workflows. As much as Apple would no doubt love the creative world to bend around it (who wouldn’t?), inviting yourself into a true professional workspace requires some concessions — namely modularity. That’s something you don’t really get with a compact enclosure.

While the company noted that the Studio was based on customer feedback, it no doubt became clear that a major segment of the market was still going unaddressed. Audio and video editors – among others – rely on cards and plug-ins that require expansion slots. The Pro’s significantly larger footprint allows for that. It also importantly provides a clearer path to upgradability than cracking open the studio.

Quoting the company:

The new Mac Pro brings PCIe expansion to Apple silicon for pros who want the performance of M2 Ultra and rely on internal expansion for their workflows. Mac Pro features seven PCle expansion slots, with six open expansion slots that support gen 4, which is 2x faster than before, so users can customize Mac Pro with essential cards. From audio pros who need digital signal processing (DSP) cards, to video pros who need serial digital interface (SDI) I/O cards for connecting to professional cameras and monitors, to users who need additional networking and storage, Mac Pro lets professionals customize and expand their systems, pushing the limits of their most demanding workflows.

Image Credits: Brian Heater

So where does all of this leave the Studio? It’s the far more compact option of the two. It also offers a significantly lower barrier of entry. The system starts at $1,999. The Mac Pro starts at $6,999. It’s not an entirely fair comparison, of course. For one thing, the Studio has an M2 Max option, and the Pro only does Ultra. The Pro also starts with higher specs like 64GB of RAM (to the Studio M2 Max’s 32GB) and 1TB of storage (vs. 512GB).

If we configure the Studio more comparably, it comes out to $3,999 – that’s two grand more than the entry level, but still well below the Pro. A fully maxed out Studio (M2 Ultra with a 76-core GPU, 192GB of memory and 8TB of storage) is $8,800. Top out the Mac Pro with comparable specs, and you’ve entered five-digit territory at $11,800. Barriers of entry are relative.

Apple sent a nearly specked out Studio. The model, as configured, runs $6,800. That includes the M2 Ultra (24Core CPU/76Core GPU), with 128GB of memory and 4TB of storage. It’s important to note that the Studio the company sent for testing last year had the M1 Max, rather than Ultra. While last week’s keynote was light on the chip talk (rumor has it due to supply chain issues), the M2 Ultra had its moment in the sun. After all, you can’t refresh the Mac Pro without another step up in processing power.

Image Credits: Apple

So, what could be better than one M2 Max, you ask? Simple. Two M2 Maxes. The Ultra truly is a pair of M2 Max chips, combined through a process the company calls – fittingly – UltraFusion (see the above gif). So, the 12-core CPU and 38-core GPU are now 24- and 76-cores, respectively (a 60-core GPU is also available).

Per Apple:

- M2 Ultra features a 32-core Neural Engine, delivering 31.6 trillion operations per second, which is 40 percent faster performance than M1 Ultra.

- The powerful media engine has twice the capabilities of M2 Max, further accelerating video processing. It has dedicated, hardware-enabled H.264, HEVC, and ProRes encode and decode, allowing M2 Ultra to play back up to 22 streams of 8K ProRes 422 video — far more than any PC chip can do.

- The display engine supports up to six Pro Display XDRs, driving more than 100 million pixels.

- The latest Secure Enclave, along with hardware-verified secure boot and runtime anti-exploitation technologies, provides best-in-class security.

Image Credits: Brian Heater

At $6,800, we’ve obviously gone well beyond what most people would reasonably pay for a desktop system. The good news for them is that the Mac Mini and iMac are far more accessible, and much like the MacBook Air, offer more than enough firepower for day-to-day tasks (gaming is the one major exception – though Apple still has a lot of work ahead of it in that world). My answer is effectively the same as it is with the Air vs. Pro conversation: If you don’t find yourself regularly performing resource-intensive tasks for work, you’re most likely going to be perfectly content with a more entry-level machine. Apple silicon has raised the performance floor a good deal across the line.

Physically, the new Studio is indistinguishable from last year’s model. It’s a hollowed-out chunk of machined metal brushed with the customary Mac gloss. Even the reflective Apple logo up top borrows directly from the MacBook line. At 3.7 inches, it’s a little under three times the height of the Mini (the Pro stands nearly two feet tall) and 0.2-inches longer and wider than the Mini’s 7.75 inches. In addition to components, the taller size adds in necessary airflow, but it’s still small enough to live under your Studio Display. It’s quite dense, weighing in at 5.9 pounds to the Mini’s 2.6. The Pro is in a weight class all its own at 37.2 pounds.

Holes are machined out of the front for two USB-C/Thunderbolt 4 ports and an SD slot. If you keep the system on your desk – as I suspect most will – that’s easy access for photographers. It’s a nice improvement over having to fumble around the back of the system, like on the iMac. The Mac Pro is more likely to end up on the floor, but it’s thankfully backward-compatible with the extremely Apple wheels.

On the right side of the Studio’s face is a small circular light that glows white when the power’s on. Around back, you’ll find four more USB-C ports, a pair of USB-As, an HDMI port, the power plug, headphone jack and Ethernet. There’s also a small power button that’s flush with the case. Moving that in front would have made things a bit easier, but I suspect the decision was – in part – an aesthetic choice. The computer sits atop a circular vent that draws cool air in and expels heated air through the large grille that runs the length of the rear. I moved out an old Studio to ready the desk for the newer model and found that a thick ring of dust had collected around the edge. If your place tends to get dusty (mine does, courtesy of a rabbit that seems to shed all year), you should clean the area semi-regularly. First, it gets kind of gross, and second, you don’t want to clog your computer’s fan.

The system features a single built-in speaker, versus the Studio Display’s six-speaker array. The sound is underwhelming, and it seems clear the company (very rightly) anticipates that most people who pick the system up will be relying on external speakers. If you edit audio or video professionally – or even as an amateur – I don’t need to tell you not to use this thing as an audio monitor.

Image Credits: Apple

The Studio Display itself didn’t get a refresh. That’s mostly fine. Displays generally have a significantly longer refresh cycle than computers, which get a new chip every year or so. The biggest issue with last year’s model was that terrible webcam quality. Apple improved it via a firmware upgrade, but I still rely on an external webcam. The camera on a $1,599, 27-inch, 5K display really ought to be better in this age of teleconferencing. If you really want to splurge, there’s the $4,999, 32-inch, 6K Pro Display XDR – though that one forgoes the camera altogether.

The M2 Max model is capable of supporting up to five displays at once, including four 6K through the Thunderbolt ports on the rear and one 4K display via HDMI. The Ultra bumps that up to eight displays total, including:

- Eight displays with up to 4K resolution at 60Hz

- Six displays with up to 6K resolution at 60Hz

- Three displays with up to 8K resolution at 60Hz

Image Credits: TechCrunch

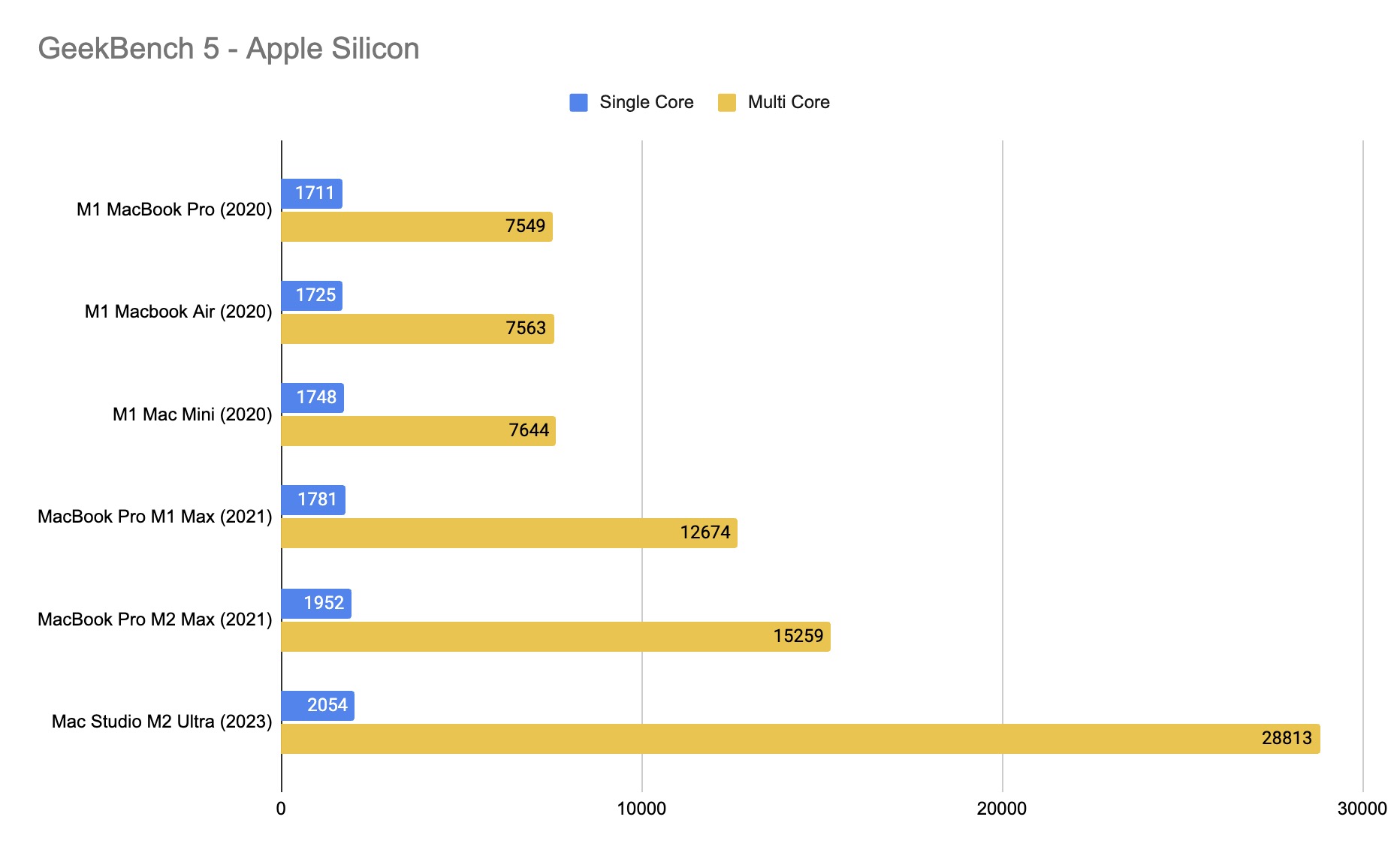

Performance numbers have been something to behold in my benchmarking thus far. The M2 Ultra Mac Studio scored an average of 2,054 on single-core and 28,813 on multi-core in Geekbench 5; compare that to the 1790 and 12,851 on our M1 Max Mac Studio tests last year.

Moving to GeekBench 6, we scored an average of 2,819 on single-core and 21,507 on multi-core. That smokes the average of 2,379 and 17,579 for the M1 Ultra system in the GeekBench archive. It’s also about in line with the 20% speed bump the company promised in its promotional material. It’s also right around double the score of the top Intel Macs. Notably, Apple largely compares its gains against its own machines. Presumably it will phase out the Intel comparisons eventually.

Image Credits: TechCrunch

As for that 76-core GPU, running the Metal test in GeekBench 6 gave us an average score of 221,340. That’s a significant increase over the M1 Ultra’s average 150,407. The figure places the M2 Ultra between NVIDIA RTX 4070 and 4080. Higher-end GPUs like the RTX 4090 continue to outpace the system graphically, but relative to its own performance, Apple’s come a long way in a short time. Given that these systems are built with creative workflows and power efficiency in mind, there’s an extent to which comparisons to the likes of NVIDIA and AMD aren’t exactly one-to-one.

Increasingly focusing on gaming is going to inevitably and understandably invite these comparisons, however. NVIDIA and AMD built intensely powerful graphics cards with numbers Apple won’t soon touch. But gaming also isn’t destined to become Apple’s driving force on the desktop, although it’s a nice and much-needed addition, as Apple ramps up its graphics game.

Gaming has been a decades-long white whale for the company. Steve Jobs was, infamously, not a fan of them – or, for that matter comics (“I hate them more than I hate video games”). Apple ceded the market to Windows long ago, in favor of a more simplistic approach to the market. In a world where gaming has eclipsed all other forms of media, however, supporting the industry is central to a full computer experience.

The company has done an excellent job taking on the mobile market, but desktop has proven an uphill battle. Taking the eye off that particular ball has allowed Windows what amounts to a decades-long head start. Gaming was largely allowed to languish, while Apple focused on other elements. But as with other key elements, in-house silicon offers a powerful foundation to begin building back.

“With Capcom bringing Resident Evil across, and other titles starting to come along, I think the AAA community is starting to wake up and understand the opportunity,” VP of Worldwide Product Marketing Bob Borchers told Matthew back in February. “Because what we have now, with our portfolio of M-series Macs, is a set of incredibly performant machines and a growing audience of people who have these incredibly performant systems that can all be addressed with a single code base that is developing over time.”

Image Credits: Brian Heater, No Man’s Sky by Hello Games

That, coupled with developer tools like Metal and the 2010 arrival of Steam have laid the groundwork for a comeback of sorts. But the results are no doubt coming slower than Apple would prefer. I played some No Man’s Sky this morning. The game just dropped on Steam and is set for the Mac App Store soon. Aside from a bit of stuttering on warm up, it was a smooth experience. With the M2 Ultra, you can push things to a 3840 x 2160 resolution (peep the new Metal Performance HUD in the above gif).

It runs smoothly, and the extraterrestrial fauna look brilliant on the display. The 76-core GPU handles the game brilliantly (the Studio gets warm – but not hot – to the touch). It’s a clear indication of where things are going, and in future generations, such performance will begin trickling down to lower-cost machines eventually (again, this setup is very cost-prohibitive for most).

But it was one of two recommended titles – the other being Resident Evil Village. There aren’t currently a lot of what you’d deem “bleeding edge” titles on Macs. No Man’s Sky arrived on Windows seven years ago. The Resident Evil title is far newer, having arrived on macOS and Switch a little over seven months after their Windows/Xbox/PlayStation debuts. Apple’s clear goal is simultaneous release dates. Making easy-to-use tools available to developers is a big piece of that, but so, too, is convincing studios and publishers that the audience is there.

Customization is also going to be a sticking point for gamers. A big piece of Apple’s approach to removing user friction is the “it just works” design philosophy. That means customization your system at check out using components made specifically for Apple systems. But many gamers love to build. They love the edge and experience that come with popping in a new graphics card. The Mac Pro offers more potential for customization, but again, it’s a machine built for creative professionals, first and foremost.

Last week’s WWDC keynote introduced us to three new Macs: the 15-inch Air, Mac Studio and Mac Pro. The trio present a fascinating little microcosm, as Apple finally gets across the prolonged transition to first-party silicon. The 15-inch Air (along with its 13-inch sibling) represents the raised floor for the line. These entry-level systems signify impressive processing gains at the low end for the company. They’re also the MacBooks I would recommend for most users.

Image Credits: Apple

The Mac Studio and Mac Pro, on the other hand, represent the current upper limits for the line. The M2 Ultra that powers the systems is – quite literally – two M2 Max chips fused together. The performance numbers are accordingly impressive, representing a company that has rekindled its love affair with creative pros after what felt like a few years in the wilderness. Given the company’s current cadence of chip updates, it’s exciting to imagine where things are going.

Graphical advancements are impressive, as well, but the company has a ways to go on the gaming front. That’s currently an issue with content as much as everything else. The transition to first-party silicon didn’t happen overnight, and that’s even more the case on the gaming side. Apple has never been known for its modesty, but I suspect even it would admit that there’s still a lot of work to be done on that front.

Image Credits: Brian Heater

As with the Air on the laptop front, the iMac or Mac Mini (depending on your monitor situation) are more than enough for most users doing most things. The Studio starts being a serious consideration when audio and video production or 3D rendering are your job. If you regularly find yourself having to work with 8K video or production music comprising hundreds of tracks, you need serious firepower.

The Mac Pro, meanwhile, is an interesting case study. It’s an artifact of understanding that truly appealing to industry professionals doesn’t happen in a vacuum. It’s a return to the modular desktop that is a tacit acknowledgement that cards and existing workflows mean a shiny new Mac Studio doesn’t always slot in as cleanly as hoped.

Those who need PCIe expansions slots, additional ports and upgradable storage will need to shell out a few extra thousand for the Pro. For a majority of those who need something more powerful than a Mini, the Studio is a significantly easier – and cheaper – bet.

[ad_2]

Source link