[ad_1]

In the early 19th century, a series of original murals were found in the former home of famed Spanish artist Francisco de Goya. The artworks, dubbed his Dark (or Black) Paintings, were painted almost entirely with dark and black pigments and portrayed bizarre and frightening themes to match. Each one strayed far beyond his typical Romantic art style and the explorations in socio-political challenges that had earned him a reputation as “the last of the Old masters and the first of the Moderns.”

The unique series was discovered years after Goya’s death, with no title, date, signature, or description, leaving art scholars scrambling to interpret the grotesque and twisted imagery for centuries. Though the Dark Paintings have come to be regarded as some of the most famous artworks of all time, many cannot bear to look at the gruesome images.

Gather your courage to take a closer look at the series and the artist who created them with 10 facts about some of the most disturbing artworks ever made: Goya’s Dark Paintings.

Related: 10 Darkest Fairy Tales

10 A Successful Artist Turned Recluse

Francisco José de Goya y Lucientes, more commonly referred to as Francisco de Goya, was born on March 30, 1746, in a small town called Fuendetodos. He passed away on April 16, 1828, at 82 years old. Starting out as a boy of 14, Goya studied art in Spain and Italy before becoming a public painter in the city of Zaragoza.

Goya later started working for the Royal Court, where he painted figures of Spanish nobility. He was greatly affected by the famine, poverty, and cruelty he witnessed during the war between France and Spain, inspiring some of his most famous—and somewhat controversial—paintings. These included some nudes and artworks which offered dark critiques of the bloody Peninsula war.

Despite his early success, Goya’s life and career took an unfortunate turn in his final years when he grew disillusioned by the restoration of the Spanish monarchy under King Ferdinand III. He became almost a total recluse from 1820 to 1823, living in isolation as he suffered from failing health and deafness that resulted from an illness decades prior. During this time, he created fourteen murals that would later become known as his Dark Paintings.[1]

9 A House with Dark Walls

Goya created his enigmatic Dark Paintings inside his villa, Quinta del Sordo (translated as House of the Deaf Man), just outside Madrid. Surprisingly, the home was not named after him. Its previous owner was also deaf. Goya painted each of the murals directly onto the walls of his two-story villa, with some on the ground floor and others on the second (or upper) floor.

The Baron Èmiole d’Erlanger, who purchased Goya’s home in 1873, removed the murals from the villa and had them placed on a canvas for display. He then donated the paintings to the state. Unfortunately, the artworks suffered enormous damage in the removal process and required extensive restoration.

Goya’s murals were not commissioned or sponsored, leading many to believe they were part of his personal commentary. Each artwork’s exploration into different religious and mythological narratives with themes like death, aging, conflict, and evil seems to support this theory.[2]

8 Two Old Men (or Two Monks)

One of Goya’s Dark Paintings, Two Old Men (or Two Monks), depicts a hideous figure with an animal-like head that appears to be shouting into the ear of a bearded old man. The man is leaning on a shepherd’s crook and has a surprisingly even, meditative expression. He is strikingly similar to a subject in a previous painting which was thought to be a self-portrait, leading many to believe that he represents Goya himself.

In the painting, the man’s dress is said to be religious in nature. On the other hand, the wide-mouthed creature carries hallmarks of how Goya depicted demonic creatures in other artworks, according to respected art critic and writer Robert Hughes. Despite the suggestion of both titles that the two subjects are alike, it is clear that something unsettling is happening between them. Though what that is exactly is still up for interpretation.[3]

7 Atropos (The Fates)

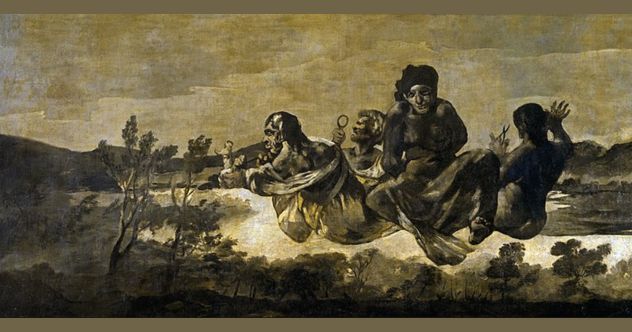

Atropos (or The Fates) is most likely based on the three Moirai in Greek mythology charged with deciding the fate of every human living on Earth: sisters Atropos, Clotho, and Lachesis. As the story goes, Atropos holds the shears to cut the thread of life and determines how each human dies. Clotho spins the thread, and Lachesis measures its length.

Goya’s versions of the Fates appear much harsher and more unnerving than they were typically pictured. Many attribute their monstrous appearance in the artwork to his feelings towards his own cruel fate. The theory seems to be supported by a fourth figure, pictured at the center, who looks out at the viewer and appears tied up with the thread.

Rumor has it that this subject represents human life as a helpless victim of fate and, ultimately, Goya’s feelings of being trapped by ill-health and old age.[4]

6 The Dog (or The Drowning Dog)

Deemed “the world’s most beautiful picture” by artist and writer Antonio Saura, The Dog (or The Drowning Dog), has one of the more lightly colored palettes of Goya’s Dark Paintings. Only a portion of the work’s sole subject is visible, a small head of a dog. The rest of its body remains hidden behind a large area of color that was not defined.

The dog is positioned in front of negative space and appears as though looking off toward something or someone just beyond the composition. In his book Goya: The Origins of the Modern Temper in Art, Fred Licht notes how the viewer is left to choose whether the dog is sinking in quicksand or if its body is cut off from the viewer’s perspective by a smaller peak in the foreground.

Symbolism often ties dogs to faithfulness, a connection Licht says tempts viewers to interpret the dog’s patient gaze as devotion. The fact that Goya was a known dog lover may add some extra credibility to this theory. Some have concluded that The Dog is a criticism of humanity’s hopelessness in the absence of God. Others claim it represents the inevitability of death. The meaning of this work, more than any of the others in the series, relies heavily upon the viewer’s mood as they experience it.[5]

5 Witches’ Sabbath (or The Great He-Goat)

In The Witches’ Sabbath (or The Great He-Goat), a large figure of a black-cloaked goat sits in the foreground, bleating something unknown to a sabbath of witches. The billy goat is thought to represent Satan himself. A small figure in white sits apart from the rest, leading many to consider the scene as the initiation of a new witch to the coven.

Some viewers are surprised to learn that The Witches’ Sabbath is not meant to be taken literally. Instead, the sinister supernatural scene serves as “a satirical criticism of what Goya saw as the ugly and dark side of the human condition and the depravity of post-Napoleonic war society that surrounded him.” Others say it is a critique of the church, whose control was steadily increasing in the years that Goya lived at Quinta del Sordo.[6]

4 Two Old Ones Eating Soup

Two Old Ones Eating Soup, also known as Two Witches, The Witchy Brew, or even Two Old Men Eating, is the smallest of the paintings and was the most well-preserved. It reportedly resided on the ground floor of Goya’s villa.

In the artwork, Goya sat two gruesome-looking figures at a table, eating. The subject on the right appears to have a skull for a head, which has led many viewers to associate the scene with death. Despite his current state of decomposition, the skeleton figure is still “eating like crazy, trying to get all he can.” Some scholars believe that the imagery translates as a kind of joke about greed or glutton.

“Look at the expressions on the faces in these paintings,” urges Manuela Mena, the former deputy director for conservation and research at the Prado Museum, “how each is a different personality. They’re not real, they’re caricatures, but they show Goya’s deep interest in human beings, in what we do and why. He was almost like a writer in a way, learning the worst about people and laughing about it in his work.”[7]

3 Saturn Devouring One of his Sons (or Saturn Devouring His Son)

Goya’s Saturn Devouring His Son (or Saturn Devouring One of His Sons) depicts the Roman god Saturn cannibalizing his son. Saturn, the god of agriculture, time, and other traits, was originally the Greek Titan Cronos. As the myth goes, Cronus feared a prophecy that he would be overthrown by his own son. So he swallowed each of his children as they were born. His wife, Rhea, managed to save the youngest, Zeus, by hiding him away on the island of Crete and fed Kronos a stone wrapped in swaddling clothes.

In the artwork, Saturn sits on one knee while tightly clasping onto the dead body of one of his children with both hands. With his mouth wide open, he readies to chew off the next part of the child’s arm. Saturn’s eyes are bulging and wild in their gaze, a detail that some have taken to represent “shock at his own monstrousness.” Scholars have often wondered if the harrowing scene is a metaphor for “the devouring nature of life in all its facets and death in all its gore.”

Other interpretations suggest that Saturn Devouring His Son is a possible symbol of the darkness Goya witnessed and experienced in his life. Jay Scott Morgan’s article “The Mystery of Goya’s Saturn” in the New England Review attributed the scene to the traumatic loss of his own children.

Goya and his wife, Josefa Bayeu, had eight children but tragically lost seven either in their early childhood or through miscarriage. A sketch of a similar scene created in 1797 suggests Goya was already considering the idea for a few years before bringing it to life in the Dark Painting.[8]

2 Conflicting Theories Regarding the Dark Paintings

Goya’s mysterious and symbolically-charged Dark Paintings have been studied so much since their discovery that they almost reached a point of overanalysis. Many believe the works speak to the artist’s mindset, claiming he was “crazy, melancholic, pessimistic when he made them.” Others argue that he was an optimist with a great sense of humor and a rational and clear thinker up until the end of his life.

Some even claim that the Dark Paintings were not actually painted by Goya at all, suggesting that they were created by his son, Javier, or grandson, Mariano, to make extra money off the sale of the villa. It has also been said that they might be the work of another artist, namely Juan José Junquera or Nigel Glendinning. However, most experts have disputed the possibility that someone else painted the Dark Paintings, asserting that “Goya’s hand is there.”[9]

1 Other Works and Further Discussion

Other works in Goya’s Dark Paintings include Asmodea (or a Fantastic Vision), Fight with Cudgels (or The Strangers), Judith and Holofernes, La Leocadia, Men Reading, the Procession of the Holy Office, a Pilgrimage to San Isidro, and Women Laughing.

The series offers a full range of “heightened emotional states like anguish, loneliness, gloom, and some smiles and laughter here and there, but even these appear hair-raising at times.” All fourteen paintings are on display in the Museo Nacional del Prado in Madrid, along with some of the artist’s other works, as part of a permanent collection. The paintings are also available for viewing on the museum’s website. More information on Goya’s Dark Paintings can be found on YouTube, with recommended videos posted by Can Özgar and Blind Dweller.[10]

[ad_2]

Source link