[ad_1]

Disclo CEO and co-founder Hannah Olson was diagnosed with Lyme disease when she was in college. At the time, she didn’t really see herself as someone with a disability, even though it meant spending hours each day hooked up to an IV.

When she entered the workforce, she soon was confronted with the difficulties of navigating, disclosing and asking for support around her condition. “I had no clue about this process, but I saw first-hand just how uncomfortable it was.” That lack of knowledge is what would kickstart her entire entrepreneurial journey – from spending time as a disability employment advisor, to building her first company, Chronically Capable, with a former boss, Kai Keane.

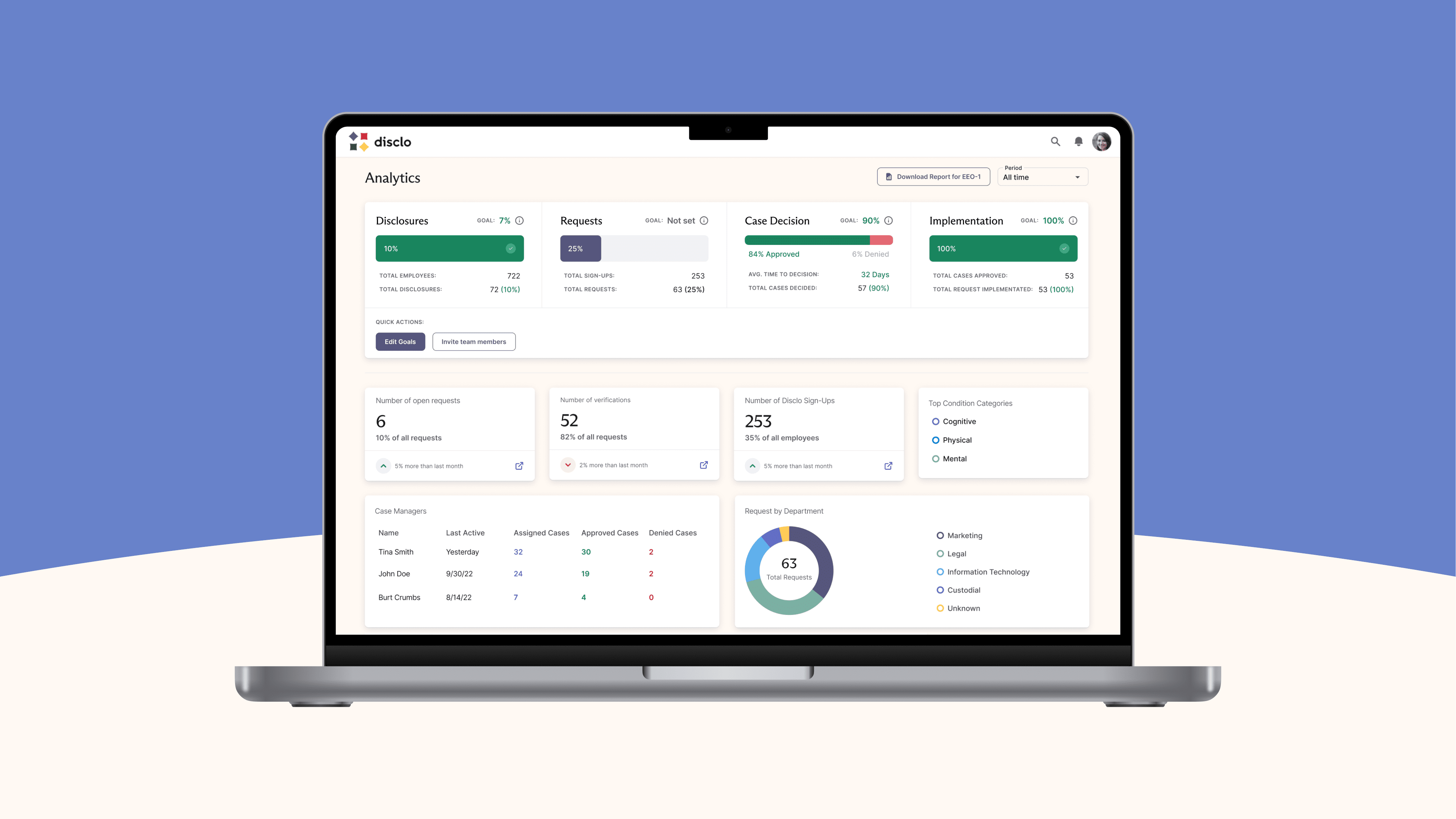

Chronically Capable helps people with disabilities and chronic illnesses find flexible jobs, and now, after scaling it for nearly five years, the founding duo has built another company that takes an earlier step in a similar world. Disclo, an Atlanta-based startup, is building software that helps employees ask for accommodation requests at work, and it empowers employers to collect, verify, and manage health disclosures and employee accommodation requests in a HIPAA and SOC2 compliant way.

Image Credits: Disclo

Investors think it is addressing a real need in the market, with General Catlyst leading a $5 million seed round in Disclo, joined by Y Combinator, Bain Capital Ventures and Lerer Hippeau. With $6.5 million in known funding altogether so far, Disclo has also tucked in Chronically Capable underneath its umbrella given the synergies between the two. While Chronically Capable is all about recruiting talent with diverse needs, Disclo helps startups to ensure they offer proper accommodations process in place first to support their hiring.

It’s not a matter of startups being thoughtful, says Keane, who is the chief product officer (Olson is CEO). It’s about following established regulations.

“We don’t think about this as going the extra mile – it’s a compliance issue,” he says. “You are following the law, and a lot of companies right now don’t know how to or they just aren’t,” he says.

At the same time, Disclo hopes its mere existence raises awareness about these regulations, for the benefit of everyone involved. “There’s some stigma and hush hush about asking for things at work, and [employers] don’t advertise how to ask for accommodations at work.” Disclo’s job, from Keane’s perspective, is to help employees understand what their rights are and to protect the employer by documenting and standardizing an often unstructured conversation.

Adoption is particularly important in times such as these, argues Olson, who notes that based on data from the last recession, tech outfits are more likely to see employees sue more often and for higher amounts because they are more motivated financially to do so.

Even if the economy recovers quickly, remote work has also created pressure around employers finding better tech to support a distributed team. Olson said that there has been a 61% increase in accommodation requests from employees – a stat that she thinks shows the need for employers to take disability requests more seriously.

A key aspect of Disclo’s software is that it anonymizes what an employee’s disability is, instead telling the employer that the individual has filed a disability notice and could use the following accommodations to feel more supported at work. This could help given that not all disabilities are visible, and not every person with a disability feels comfortable declaring that they have one.

Olson’s personal experience underscored how it was both hard to navigate the process of disclosing and find a company that “embraced” what she needed. Disclo doesn’t force startups to provide certain accommodations, but puts a framework in place for a company to be more aware and able to support their employees.

Speaking of the disorganization that rules many startups, one may ask why the large slew of HR tech startups haven’t sought to disrupt the disability accommodation side of operations. Some startups are forced to use sticky notes and box drives because restrictive laws don’t allow information to be stored inside of human resource platforms, Olsen says, while large companies use disability insurance companies.

“A lot of companies think about accommodations from the perspective of insurance claims but accommodations encompass way more than things within the realm of insurance,” she said, such as rescheduling work, bringing in your pet or asking for closed-captioning tools. “These requests often require a conversation with a manager and we’re here to help facilitate.”

In that case, maybe tech is just late to the game. Steve O’Hear, a former TechCrunch reporter, wrote about tech companies’ lack of disability reporting in 2016.

“At its best, technology acts as an enabler for PWDs, helping to level the playing field, and therefore can be a genuine force for social mobility,” O’Hear wrote at the time. “However, since disability isn’t included in most technology companies’ public diversity reporting, what we don’t know is how well the technology industry itself is doing with regards to the number of PWDs it employs and how this compares company to company.” Noting the challenges with underreporting and a lack of general transparency around companies, He urged the tech industry to “find a way to be more accountable. “

Disclo is convinced it is the first software company working on this specific niche. Let’s see if tech is ready to be an early adopter.

[ad_2]

Source link