[ad_1]

US jobs growth slowed for a fifth consecutive month in December after the Federal Reserve’s aggressive interest rate rises squeezed economic activity even as the US labour market remained historically tight.

The world’s largest economy added 223,000 jobs in the final month of 2022, lower than the downwardly-revised 256,000 increase registered in November and well below last year’s peak of 714,000 in February. Most economists had expected a 200,000 increase.

Following December’s increase, monthly jobs growth averaged 375,000 in 2022. The number of jobs added has fallen every month since August.

Despite the slowing of the pace of jobs growth, the labour market still shows a resilience that will probably compel the Fed to continue raising interest rates this year.

The unemployment rate unexpectedly fell to 3.5 per cent, reverting to a historic low, data released by the Bureau of Labor Statistics showed.

“This is still a very tight labour market,” said Veronica Clark, an economist at Citigroup. “For an economist, a low unemployment rate [is] future upside risks for wages.”

However slowing wage growth in December helped to ignite a stock market rally as investors bet the Fed would not need to be as aggressive with its policy tightening in the end. Stocks were further buoyed by a sharp drop in services activity, according to ISM data released on Friday. The S&P 500 was up 1.6 per cent in late-morning trading in New York, while the Nasdaq Composite was up 1.4 per cent.

The two-year Treasury yield, which is sensitive to changes in interest rate expectations, slid 0.19 percentage points to 4.26 per cent, marking a sharp rise in the price of the debt instrument. The yield on the benchmark 10-year Treasury note, seen as a proxy for borrowing costs worldwide, fell 0.14 percentage points to 3.58 per cent.

The US central bank is actively trying to cool down the labour market and curb demand for new hires as it seeks to alleviate price pressures that have pushed inflation to multi-decade highs. Since March, the Fed has raised its benchmark policy rate from near-zero to just below 4.5 per cent in one of the most aggressive campaigns in its history.

While the worst of the inflation shock appears to have passed, price pressures have taken hold in the services sector of the economy. In an interview with the Financial Times this week, Gita Gopinath, the first deputy managing director at the IMF, urged the Fed to “stay the course” in terms of tightening, arguing that inflation in the US has not “turned the corner yet”.

In remarks delivered on Friday, Lisa Cook, a Fed governor, cautioned against “putting too much weight” on recent inflation data she said looked “favourable”. She said she is “keeping close tabs” on labour costs, which she said are crucial to the future trajectory of inflation.

Amid a worker shortage that Fed officials warn will not be easily reversed, wage growth is still running at a pace far out of step with the Fed’s 2 per cent inflation target.

In December, average hourly earnings climbed another 0.3 per cent, less than expected and slower than the previous period, which was revised lower. On an annual basis, it is up 4.6 per cent. The labour force participation rate, which tracks the share of Americans either employed or looking for a job, was little changed at 62.3 per cent.

Peter Williams at Evercore said the wage data should give the Fed “comfort that inflationary pressures have peaked”.

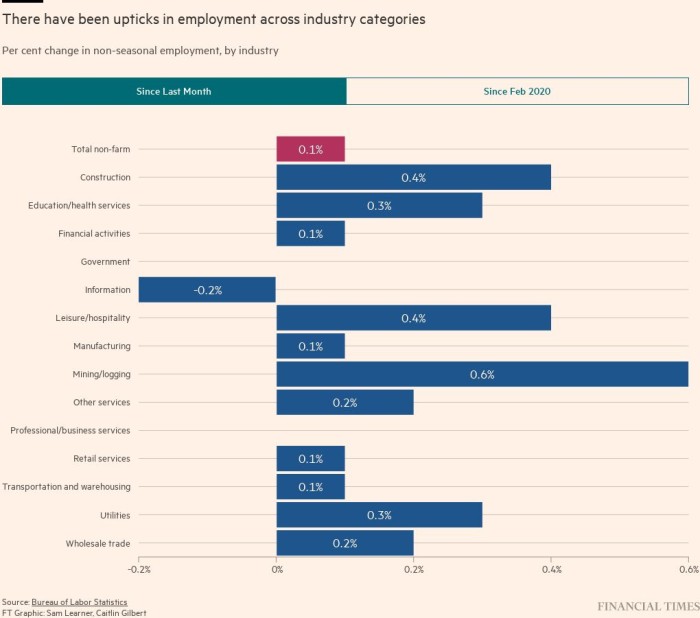

The largest job gains occurred in the leisure and hospitality sector, with 67,000 positions added in December. Healthcare employment rose by 55,000, while the construction industry gained 28,000 jobs.

Among the sectors with minimal employment gains were retail, manufacturing and transportation and warehousing.

In a statement released after the report, president Joe Biden said the latest jobs gains reflect “a transition to steady and stable growth”.

“These historic jobs and unemployment gains are giving workers more power and American families more breathing room,” the US president said, amid a “cost-of-living squeeze”.

Policymakers at the Fed have acknowledged that stamping out inflation will require job losses and in turn a higher unemployment rate. According to the latest individual projections published by the Fed, most officials see the unemployment rate rising as high as 4.6 per cent this year and next as the benchmark policy rate surpasses 5 per cent and is held there for an extended period.

“Holding [above 5 per cent] until we get evidence that inflation is actually coming down is really the message we’re trying to put out there,” Esther George, the outgoing president of the Kansas City Fed, said on Thursday.

Striking a similar tone this week, Neel Kashkari of the Minneapolis Fed said he expects the central bank to raise the federal funds rate by another percentage point over the coming months. He will be a voting member on the policy-setting Federal Open Market Committee this year.

Traders in federal funds futures broadly expect the Fed to advance towards that so-called “terminal” level in smaller increments than the half-point and 0.75 percentage point rises it has used throughout this tightening campaign. According to CME Group, the odds of a quarter-point rate rise at the February meeting currently stand at 65 per cent.

“Now, with forward-looking real rates positive across the curve and therefore our foot unequivocally on the brake, it makes sense to steer more deliberately as we work to bring inflation down,” Tom Barkin, president of the Richmond Fed, said in remarks on Friday.

Should the Fed follow through with its plans, economists warn more material job losses could be on the horizon. Those polled last month in a joint survey by the FT and the Initiative on Global Markets at the University of Chicago Booth School of Business forecast the unemployment rate reaching at least 5.5 per cent next year as the economy tips into a recession.

Additional reporting by Harriet Clarfelt in New York

[ad_2]

Source link