[ad_1]

Eurozone inflation almost certainly fell back into single digits for the first time in three months in December, with data published earlier this week showing price pressures eased by more than expected in Germany, France and Spain towards the end of 2022.

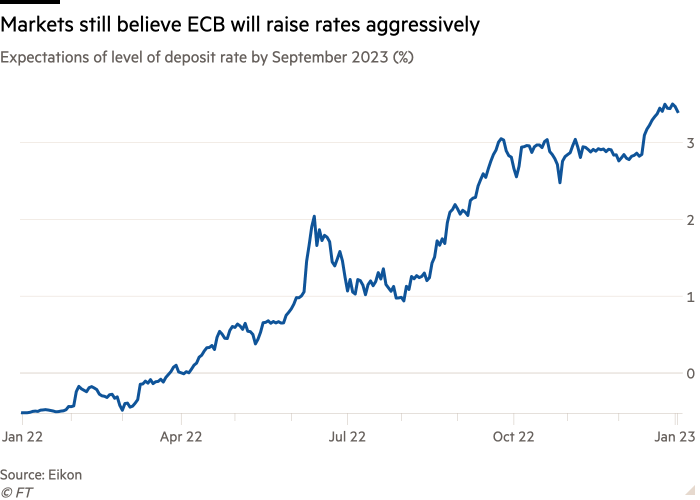

Yet the slowdown is unlikely to be enough to convince the European Central Bank to stop raising interest rates just yet, with markets still pricing in a series of increases by officials in Frankfurt over the course of 2023.

Franziska Palmas, senior Europe economist at research group Capital Economics, said: “The ECB is likely to stick to its hawkish rhetoric in the near term despite the big falls — and likelihood of further sharp declines this year.”

Why are the falls not enough to convince the ECB to change tack?

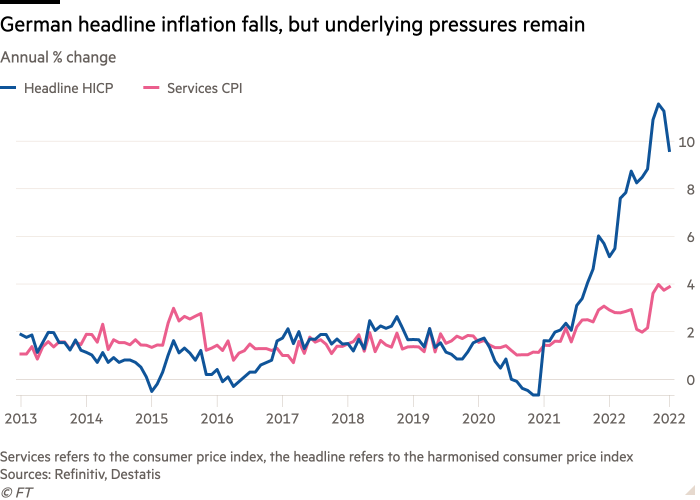

While falls in fuel prices and government subsidies to help businesses and households out with higher power bills have cut headline inflation rates, underlying price pressures remain strong.

Berlin paid most households’ gas bills for December, which Commerzbank economists estimated knocked 1.2 percentage points off the harmonised rate of headline inflation. The rate fell to 9.6 per cent, down from 11.3 per cent the previous month. But growth in the cost of services, an indicator of how long price pressures are likely to endure, accelerated in December.

In Spain, core CPI inflation — which excludes movements in the price of food and energy — rose in the year to December, despite a sharper than expected fall in the harmonised headline rate to 5.6 per cent.

Although headline inflation in the eurozone fell from the 10.6 per cent record hit in October to 10.1 per cent in November, core inflation — at 5 per cent — remained at an all-time high. It is expected to stay there in December.

“This year will be mostly about getting under the hood of inflation and seeing exactly what is driving it,” said Paul Hollingsworth, chief European economist at French bank BNP Paribas.

For the ECB to change tack, rate-setters will want to see a substantial fall in the core rate and other measures of longer-term inflationary pressures, such as wage growth. They will also be on the lookout for signs that governments’ support for households and businesses struggling with high energy prices is boosting demand.

Christine Lagarde said in an interview with Croatian newspaper Jutarnji List: “We need to be careful that the domestic causes [of inflation] that we are seeing, which are mainly related to fiscal measures and wage dynamics, do not lead to inflation becoming entrenched.”

What’s next for inflation in Europe?

Economists polled by Bloomberg forecast a drop in eurozone inflation to 9.5 per cent in December, down from 10.1 per cent in November. The data, published by the European Commission’s statistics bureau Eurostat, are out at 10am UK time on Friday morning.

Further falls are expected in the coming months, following the slump in energy prices since the start of the year. The impact of last year’s surge in power costs following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine will also soon fall out of the index, lowering the headline figure substantially.

Carsten Brzeski, head of macro research at Dutch bank ING, predicted that euro area inflation could even drop back to the ECB’s 2 per cent target by the end of 2023.

If the recent falls in gas prices continue, the ECB will almost certainly have to downgrade its inflation projections for this year. The central bank said in December that prices would rise 6.3 per cent over the course of 2023, based on assumption for natural gas prices to average €124 per megawatt hour over the whole of this year.

But the price of the Dutch TTF benchmark European gas contract has fallen about 10 per cent this week to just €69.70/MWh as of Thursday afternoon — a level 80 per cent below the August high of €340/MWh.

“The ECB’s own inflation projections are currently too high, just judging from the technical assumptions for gas and oil prices and where these prices are currently,” said Brzeski.

What does this outlook mean for interest rates?

Last year, the ECB responded to soaring inflation by raising interest rates at an unprecedented pace, lifting its deposit rate from minus 0.5 per cent in July to 2 per cent by the end of the year.

ECB president Christine Lagarde said in December that markets were underestimating how much higher borrowing costs would go, adding: “We should expect to raise interest rates at a 50-basis-point pace for a period of time.”

Since then, investors have been pricing in about 1.5 percentage points of rate rises over the opening three quarters of 2023.

Two half-point rate rises at officials’ next two policy meetings in February and March and a few smaller moves later in the year remain the expectation, despite the sharper than expected falls in inflation this week.

Without sharper falls in measures of underlying price pressures, markets’ and economists’ expectations for eurozone interest rates are unlikely to shift by much.

“It is all very well getting back to 3 or 4 per cent inflation,” Hollingsworth said. “But it could be harder to get down to 2 per cent, particularly if there is a milder than expected recession.”

He added: “We really need to see services prices and wage growth cooling to convince the ECB it has done enough.”

Additional reporting by Valentina Romei

[ad_2]

Source link