[ad_1]

The world used to be a very big place. Traveling long distances was a costly and dangerous task that might take months. Aside from a few traders seeking raw goods and armies following a general hungry for glory, not many people saw much of the globe in antiquity. What few facts they could gather from faraway places were often filtered through multiple re-tellings. And the stories about foreign people grew wilder with each recounting.

Here are ten tribes of humanoids that were once thought to live at the edge of the known world.

Related: Top 10 Cryptids Easily Explained By Real Animals

10 Headless Men

The Greek writer Herodotus wrote his history in the 5th century BC. He did not, however, constrain himself to pure history. His works are full of anthropological details about societies that the Greeks had heard of. Because he was not always accurate in what he wrote, Herodotus is not only known as the “Father of History,” but he is also called the “Father of Lies.” One of the peoples he wrote about he called the akephaloi—the headless people.

According to Herodotus, these people with their features in the middle of their chests lived on the edge of Libya. The Roman writer Pliny the Elder called these people Blemmyae. Interestingly, there were real people known as Blemmyes who lived to the south of Egypt. As far as we know, though, their heads were in the place you would normally expect.

In medieval texts and maps, the headless men were a popular motif. As trade with Africa, and knowledge of the people there, increased, the home of the headless men moved ever further east. When Sir Walter Raleigh wrote about the discovery of Guiana, he reported rumors of a tribe of headless people called the Ewaipanoma living beside a river there.[1]

9 Androphagi

Not all the strange human tribes that lived beyond the known world looked weird; sometimes, it was their habits and customs that shocked the Greeks. The Greek world was split into many different types of societies ranging from democracies to monarchies to oligarchies to monarchies. They loved to investigate the ways other cultures lived. One that fascinated them was the idea of cannibal groups.

Herodotus mentioned a group that ate human flesh. He called the group the Androphagi—from the Greek word meaning man-eating. He says, “their manners are more savage than those of any other race.” Pliny the Elder also lists the man-eaters among “the Agriophagi, who live principally on the flesh of panthers and lions, the Pamphagi, who will eat anything, [and] the Anthropophagi, who live on human flesh.”[2]

8 Gorgades

Pliny the Elder, writing a comprehensive text of all knowledge in the 1st century AD, included tales from places few or no Romans would have visited. In his text, he described a set of islands off the Atlantic coast of Africa that he called the Gorgades. Pliny reports that the women of the people who lived there were covered head to toe in thick fur.

But Pliny’s is not the only account we have of these people. Writing a century earlier, Pomponius Mela said that the islands were populated purely by these hairy women—and that they reproduced without the need for men. These wild women were savage and strong. They could only be held still by the use of chains.

Pliny records that it was the Carthaginian explorer Hanno who visited the Gorgades. To prove that he had seen such people, he apparently brought back two skins of these women and hung them up in a temple in Carthage. Were these skins real? Did they represent a species of ape that explorers had encountered?[3]

7 Astomi

The eating habits of other cultures can be shocking to some. Pliny the Elder was particularly fascinated by the things people put into their bodies. That was why the Astomi interested him so much.

According to Pliny, this tribe lived near the source of the Ganges in India. These people not only did not eat food familiar to Greeks and Romans, but they also did not feed on food at all. This is perhaps explained by the fact they had no mouths. Instead, the Astomi survived by sniffing the scents of flowers and fruit. To travel on long journeys, they would carry perfumed items with them as a source of energy.

There was a downside to their diet, however. Apparently, strong odors of the wrong sort could prove deadly.[4]

6 Panotti

Some people might get surgery if they think their ears are too prominent, but they should be thankful that they were not members of the Panotti. Their very name means “all-ears.” Their ears were so large that they were used instead of clothing, and they would drape their ears over themselves on chilly nights.

Pliny, again, mentions the Panotti, but they are not his only large-eared people. He describes Indians who are entirely covered by their huge ears. Pliny also quotes an author called Ctesias, who wrote about an Indian tribe called the Pandai. The Pandai were covered entirely in white fur that turned black as they got older. They also only had eight fingers and eight toes. But it is their ears that interest us—they hung down to the elbow.

Pomponius Mela places the home of the Panotti on an island in the far north of Europe.[5]

5 Pygmies

For the Greeks and Romans, pygmies were a range of diminutive tribes that could be found in various places around the world. According to Homer, in The Iliad, the pygmies were locked in constant combat with cranes—Aristotle believed this story to be true. According to him, the pygmies lived underground and rode little horses appropriate to their small stature.

Pliny the Elder records pygmies living everywhere, from Africa to India. The Indian pygmies stood only 27 inches (68.5 centimeters) tall. The pygmies there fought with cranes because they ate the eggs of the birds. They went into battle riding on the backs of rams. By eating the eggs of the cranes, they stopped the cranes from growing up and fighting back.

A historian of the 6th century, an explorer called Nonossus, visited an island in the Red Sea by the coast of Ethiopia where the Pygmies lived. They went about without any clothes on, and their bodies were entirely covered in hair. Given their small size, the pygmies were very timid and fled from taller visitors.[6]

4 Abarimon

After conquering the Persian Empire, Alexander the Great launched a campaign into India. Among the thousands of soldiers that Alexander took was a group of scholars, geographers, and philosophers. They were tasked with recording the new lands that the Greeks were exploring. They brought back much knowledge, but not all of it seems to be entirely accurate.

Apparently, one of Alexander’s men, Baeton, was charged with exploring the passes into India. In one valley, he found a race of people with their feet backward compared to most people. Despite this seeming setback, Pliny tells us that Baeton found they could move with amazing speed.

It turned out to be impossible for Baeton to present any of these Abarimon to Alexander because they were unable to breathe any air except that found in their own valley.[7]

3 Arimaspi

At the edge of the known world, there were not only humans but weird beasts too. Herodotus wrote about ants the size of dogs that would dig up gold in India. These ants were not the only creatures associated with gold, according to the “Father of History.”

He claims that griffins (half-eagle, half-lion) would collect it too. Herodotus says that northern Europe has the most gold of any place, but he does not know how it is mined there. All he knows is that the griffins guard it there. When one being has gold, there is always another that wants it. The griffins had to fight to keep their gold from the Arimaspoi who wanted it.

The Arimaspi were humans with just a single eye in the middle of their forehead. The Arimaspi were related to the Scythians, and when Greek vase painters wanted to show a battle between the Arimaspi and the griffins, they showed them in Scythian garb.[8]

2 Cynocephali

When people think of Egyptian gods, they tend to picture a human being with the head of an animal, be it a cat or crocodile or dung-beetle. Those images were more about suggesting the power of the god than a realistic representation. There were those, however, who believed that similar mixes of animal and human really existed. The Cynocephali were a tribe of humans who were supposed to have the heads of dogs.

Ctesias was a Greek author who had been to Persia. He wrote works about India and Persia based on the royal archives of the Persian empire. Many at the time and since have doubted whether much of his work can be trusted. Among the people he described were the Cynocephali of India. They lived in the mountains and howled and barked like dogs, though they were as intelligent and reasonable as humans. Other authors placed the home of the Cynocephali in Africa.

In the Middle Ages, some icons of Saint Christopher show him with the head of a dog. This may be the result of misreading the word Cananeus (“From Canaan”) for Caninus (“like a dog”).[9]

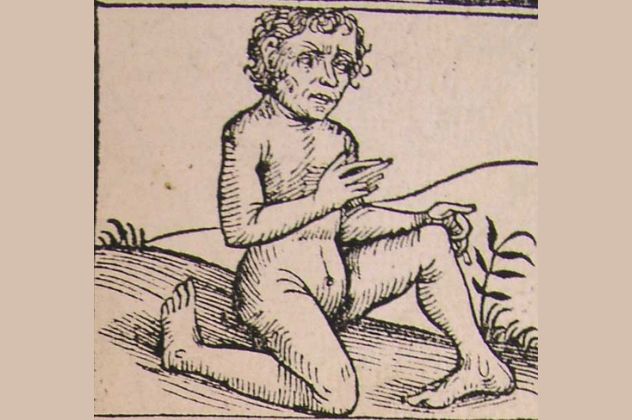

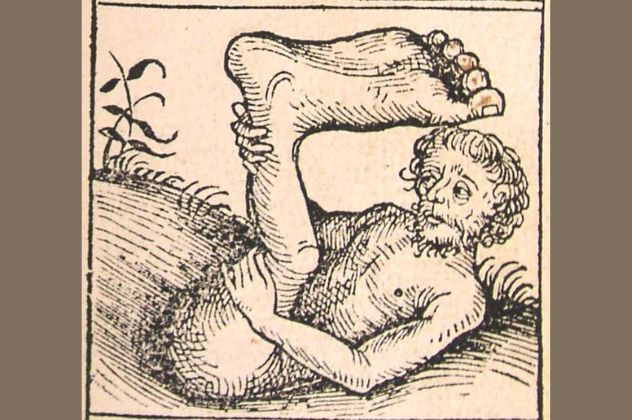

1 Monopods

You would think that having only one foot might be a disadvantage, but for one tribe of people, it was a huge benefit—almost as large as their singular foot. The Monopods, also called Sciapods, with their one big foot, became a favorite image for those who wanted to show how strange things were toward the end of the map.

In Pliny’s account, which he says draws from that of Ctesias, the monopods were able to leap about with surprising ease. They were also very quick. The land they lived in was apparently very hot and very sunny. When the weather got too much, the monopods would lay on their backs and use their feet as parasols so that they could rest in the shade.

The Christian writer St. Augustine wondered whether humanoids like the Monopods and others were descended from Adam. He came to the conclusion that if they exist, and if they have human reason, then they must be creatures with souls and therefore descended from Adam.[10]

[ad_2]

Source link