[ad_1]

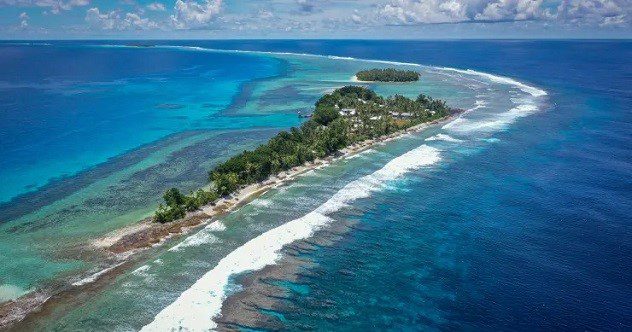

Tuvalu is the world’s second-smallest country. Only Vatican City has fewer citizens. However, the Vatican sits smack-dab in the middle of Rome. Its urban location gives its people access to a much larger community. Tuvalu doesn’t have that luxury. The nine-island chain is completely alone in the South Pacific Ocean. It sits 1,000 miles (1,609 kilometers) east of Papua New Guinea and far southwest of Hawaii. As of 2022, less than 12,000 people live in Tuvalu. Its capital city, Funafuti, is home to about half.

As you might expect, the island chain is extremely isolated. The beaches may be beautiful, but life on the islands isn’t exactly paradise. Based on per capita income, Tuvalu is one of the world’s poorest countries. Rising seas are making life in Tuvalu precarious and uncertain. Officials are scrambling, but solutions are uncertain. But through it all, Tuvaluan traditions have held strong. These ten facts show what it’s really like to live in the world’s tiniest island nation.

Related: 10 Forbidden Destinations That You’re Not Allowed To Visit

10 Tuvalu Is Tiny—Really, Really Tiny

Did we mention Tuvalu is a tiny place? If you’ve ever traveled from Hawaii to Australia, you’ve gone high above it at about the halfway point of your flight. You surely didn’t see it down below, though. That’s because Tuvalu’s nine islands make up a landmass of just 10 square miles (26 square kilometers)—combined. That’s an area about one-tenth the size of Washington, D.C.

By land mass, Tuvalu is the world’s fourth-smallest country. And that’s across nine atolls! Not one of those sites is more than a spit of land in the open ocean. Plus, the islands are spread far apart from each other. The furthest points stretch nearly 500 miles (804 kilometers) across the Pacific. Taken together, that’s thousands of square miles of open water. Seaplanes often make the trek, but it’s far more common for the local government to shuttle passengers by boat.

As we explained above, about half of Tuvalu’s population lives on Funafuti. It’s not like most world capitals, though. With just 6,000 people in town, it’s far from a bustling metropolis. Local economic services dominate. And tourism in Funafuti isn’t a major player like in many island communities. Plus, the highest elevation on the island is about 30 feet (9.1 meters) above sea level. There are no hills, no mountains, and no rivers. Just an endless ocean as far as the eye can see!

With such little land area on hand, major problems come up. Agriculture is nearly non-existent (more on that in a minute). Fresh water is supplied through catchment systems. Residents use desalination processes, too, but those are fraught due to the local landscape (more on that in a minute too). Right from the very first observation, it’s clear Tuvalu is not like anywhere else in the world.[1]

9 Ancient Migration Patterns Produced Today’s Tuvaluans

How did people get to Tuvalu, anyways? With tiny atolls so far out of the way, it’s not exactly a migration must. But the story of the ancient sailors who settled the islands is a fascinating one. Tuvalu was first populated about 800 years ago. Samoans sailed northwest and landed on many of the islands. Other people from Tonga and Micronesia settled the other atolls in the following decades. For several centuries, they lived in peace and isolation.

In the mid-16th century, Europeans arrived. First, it was Spanish explorer Álvaro de Mendaña de Neira. Like everyone else, he was thrown by Tuvalu’s isolation, and he didn’t stay for long. The Spanish mapped the atolls but never moved to colonize the place. Thus, locals lived far from European influence for another few centuries. But by the mid-1800s, Westerners often came.

In the 19th century, Tuvalu became an important stop in the “blackbirding” trade. In this disturbing business, European merchant ships would sail to the islands and dangle the promise of paid labor and attract Tuvaluan men. Once on board, the men were shipped off to plantations and farms as far away as Australia and South America. Most never returned. The kidnappings decimated the islands. In 1863, one Peruvian slave boat seized nearly 400 Tuvaluans on a single voyage. Today, some historians estimate the islands’ populations dropped from 20,000 people to less than 3,000 during blackbirding.

By the late 1800s, the slave trade had slowed. In 1892, the British decreed it to be a protectorate. They called the place the Ellice Islands. To make their work simple, the British government combined Tuvalu and the nearby Gilbert Islands into one administrative group. That pairing created tension, as the ni-Kiribati who lived in the Gilberts were ethnically Micronesian and thus culturally different from the Polynesian Tuvaluan people. Regardless, the British oversaw the area for decades. By the 1960s, calls for independence came. In 1978, Tuvalu broke off from UK rule and became independent. The next year, the Gilbert Islands did the same and became Kiribati.[2]

8 Tuvalu’s Economy Is Entirely Local… Except For WHAT?

There aren’t many ways to make money in Tuvalu. Most locals are subsistence farmers who tend to private gardens year-round. Many go out on the ocean to catch fish to eat too. But without much land, farming isn’t a big business. Plus, the lack of irrigation makes it even tougher. Thus, about a tenth of Tuvalu’s population works overseas. Many join up with merchant ships to sail for a salary. Others go to Nauru, another island in the South Pacific, to work in phosphate mines.

Meanwhile, Tuvalu must import nearly everything. Food, dry goods, and fuel are all purchased abroad from Australia, New Zealand, Fiji, and Japan. That makes the island nation very dependent on these countries. Economists are concerned about that. But without natural resources, there’s nowhere else for Tuvalu to go.

Except for the internet. When the world wide web started up, Tuvalu was given the .tv domain suffix. That makes sense considering the country’s name. But now, it’s inadvertently become an amazing source of revenue for the cash-strapped place! In recent years, English-language websites have sought .tv domain addresses for their brands. Today, the streaming site Twitch is one of the best-known, but countless companies pay top dollar for the .tv domain.

For Tuvaluans, that means an influx of much-needed cash. “It enables the government to provide essential services to its people through providing schooling and education for the kids and providing medical services to our people,” Minister of Finance Seve Paeniu told The Washington Post back in 2019. “And also in terms of improving the basic economic infrastructure and service delivery to our communities.” It may not be a traditional economic model, but it’s working for Tuvalu![3]

7 Money Matters Aren’t Simple, but They Could Be Soon

Speaking of money, that’s always an issue in Tuvalu. The far-flung nation doesn’t have access to most modern banking systems. In fact, there is no central bank that oversees monetary policy on the islands. Its residents are served by just one outfit—the National Bank of Tuvalu. The government owns about half of that firm. Still, the bank works as little more than a deposit center. That’s because Tuvalu doesn’t even have its own currency! It used to mint coins abroad, but that was costly and inefficient. In recent years, Tuvalu has replaced its currency with the Australian dollar.

Using foreign currency provides stability, but there are other issues to consider too. For one, Tuvalu doesn’t have any ATMs. Digital banking is non-existent on the islands. Locals carry cash everywhere. Remember how we noted about 10% of Tuvaluans work abroad? When they go abroad, they take their money with them. Thus, cash shortages on the atolls are not uncommon.

Thus, Tuvalu has been forced to think about its financial future. For one, leaders understand they must bring the island nation into the modern era. And that means joining the digital economy. While the .tv domain boom has been great, Tuvalu needs more. The nation is now looking into whether cryptocurrency could play a part in that role. Moving to a digital currency would be a major risk, but officials hope it could stabilize Tuvalu’s cash stores. In a best-case scenario, it could even help the atolls lessen their dependence on foreign aid.[4]

6 Tuvaluans Play Their Own Version of Handball

Like everywhere else in the world, sports are popular in Tuvalu. After the British made the islands part of its protectorate in 1892, cricket took hold. Tuvaluans learned the proper English version of the game and loved it. They also created their own spin on it called kilikiti. For decades, kilikiti was the country’s most popular sport.

In recent years, though, soccer has surpassed it. Just like in most other places on earth, soccer captivates Tuvaluan youth. The country fields a national team that competes in worldwide events too. But Tuvaluans also play another game unlike anything else on earth: Te Ano. This unique game has managed to combine some traits of volleyball with others from cricket and even baseball in a way unseen elsewhere.

To play Te Ano, two teams meet across a field. Each team has a captain and a catcher. The rest of the team, called the “vaka,” stands behind their captain. Play starts when the captain takes a ball covered with pandanus leaves called the “ano” and throws it to the opposing team. They bat the ball back to the vaka, who must hit it to each other by hand. Their goal is to return the ball to their catcher without it ever hitting the ground. If it falls, the batting team gets a point. If the ball makes it back to the catcher and his captain, the fielding team earns the nod. The first team to ten points wins.

The game is hugely popular among Tuvaluans. It’s even seen time on the world stage. They taught it to Prince William when he came to Funafuti on a royal visit in 2012![5]

5 Agriculture Is Very Limited & That’s an Issue

As we noted previously, food sources in Tuvalu are hard to come by. The ocean can certainly be plentiful, but fishing takes manpower and time. It can be dangerous too. And there are no guarantees on catches—especially with the throngs of commercial fishermen across the Pacific and the seasonal migration patterns of fish. Sadly, land-grown food doesn’t fare much better.

Top soils in Tuvalu are sandy, salty, and shallow. That makes them inconsistent for growing. Some things do grow well on the islands, like coconut, breadfruit, taro, and bananas. The local root crop, pulaka, is similar to taro and prized by the people. Pandanus trees thrive there too. Their leaves are used to build structures and domestic items. As far as animals go, local farmers in Tuvalu have some success raising pigs and chickens. But again, without much land, these plots are about as far from large-scale farming as one can get.

Rising seas have radically altered Tuvalu’s growing habits. In fact, pulaka has been most affected by it all. Sandy soils and unpredictable weather are putting the nation’s root crop at risk. For years, agricultural officials have advised Tuvaluans to keep planting it for the future. More recently, another problem has swept across Tuvalu: obesity. For decades, Western diets have altered how (and what) Tuvaluans eat. Agricultural challenges force the country to import most of its food. Much of that shipped sustenance is packaged and processed. Consequently, it isn’t very healthy. But it is plentiful.

Today, more than half of Tuvaluan adults are overweight. Most of the population is at risk for diabetes. The imported food combined with sedentary lifestyles is wreaking public health havoc. That problem is popping up all over Polynesia. Tuvaluan officials and others in Fiji, Kiribati, Nauru, Vanuatu, and Tonga are desperately seeking solutions.[6]

4 Music Takes Center Stage on the Islands

Along with their unique sporting history, Tuvaluans love music. Most traditional songs in Tuvalu are similar to music elsewhere on earth. Topics about love, historical events, and nature all feature prominently. Interestingly, death is specifically avoided in these traditional songs. Still, singers are held in high regard. Locals in Tuvalu greatly admire their peers who can belt it out.

That makes a lot of sense because music in Tuvalu has been heavily influenced by other cultures who also prize performance. Ancient Polynesian migrants and more modern Christian missionaries all understood the power of song. When their influences came together in Tuvalu, the result was a serious respect for the vocal arts. Today, that tradition continues.

In addition to music, Tuvaluans also love to dance. Their long-practiced two-step is called the “fatele.” Interestingly, it is unlike most dances worldwide. That’s because its participants traditionally perform the dance in a sitting or kneeling position. The moves consist of highly-specific sweeps of the dancer’s arms and hands. As the chorus chants, sings, and praises, dancers coordinate in a simple but stunning show.

Today, the tradition of the fatele continues. However, modern Tuvaluans have gotten up off their knees to move to the beat. Footwork has been added to what’s become an intricate ritual. When Prince William and his wife, Princess Catherine, came to Tuvalu on their 2012 tour, they were taught the fatele first-hand. That’s not a bad way to learn about a culture![7]

3 Family Truly Comes First in Tuvalu

Because Tuvalu is such a small place, it feels like everyone knows everyone else. That’s not really true, of course. Not all 6,000 people in Funafuti are acquainted! But the island’s small-town atmosphere makes the family the focus. In Tuvalu, households are extended clans. Usually, three generations live together: parents, children, and grandchildren.

Grandparents spend their time caring for babies and kids. Parents work, clean, farm, and fish. And Tuvaluans prize their elders’ experiences. Family decisions are only made after final consultation with the oldest members of the clan. Meanwhile, gender roles are pretty traditional. Women tend to stay home and helm domestic duties. Men fish and farm, providing for the family outside their four walls.

Speaking of those walls, homes in Tuvalu are built a bit differently. The mild weather allows for more open space in a family’s compound. Traditionally, Tuvaluan families live in an open-sided structure called a “fale.” Stumps from coconut trees support walls on three sides. The fale’s thatched roof is made from pandanus leaves. Crushed coral is typically mixed into a foundation to support the walls of the structure. Meanwhile, coconut mats cover the ground and provide simple flooring.

With one side open, families come and go at ease. The good weather makes it easy (and quite literally breezy!) to live like that. In modern times, though, that tradition is changing. Especially in Funafuti, Tuvaluans now live in structures more similar to our homes. With the fale sometimes susceptible to high winds during cyclone season, these Western-style homes are growing in popularity.[8]

2 The Threat Gripping the Islands

Tuvalu’s location makes it susceptible to the slightest climactic changes. While environmental issues may be a political football in other places, the nine-island chain suffers the effects of sea level rise in real time. Locals often comment to each other about how “Tuvalu is sinking.” Sadly, there aren’t easy solutions. Sandy beaches are overcome more each year by relentless waves. And with such little land area, there isn’t anywhere to go. These changes cause other issues too.

Freshwater resources on the islands have been contaminated by rising salt water. Crop yields are down, and small farm plots have been destroyed. Even fishing grounds have changed radically compared to historical times. With local resources depleted, Tuvalu relies heavily on foreign aid. And permanent solutions are under consideration. Evacuation is a possibility, but it’s one locals don’t want. Leaving their historic homelands is a last resort. The neighboring nation of Fiji has graciously offered land for relocation, but Tuvaluan leaders have held off on taking them up.

For now, Tuvalu’s people are committed to green energy. The country’s state-owned electric company is working on converting all its power sources to renewables. In 2019, the Asian Development Bank even approved a $6 million grant for installing solar panels and rechargeable batteries across Funafuti. The island nation isn’t in an entirely renewable position yet, but they’re getting closer.

Meanwhile, officials across the Pacific are taking notice. In 2019, Tuvalu’s then-Prime Minister Enele Sopoaga spoke to the press about his nation’s next steps. “Our emissions can be tiny, but our effort to go 100% renewable energy by 2025 is a symbol of global leadership on our fight against climate change,” Sopoaga said. “Our Energy targets and our NDC targets are a symbol of our push to global leaders to reduce their emissions.”[9]

1 At Least Tuvaluans Don’t Fight over Political Parties!

Clearly, Tuvalu faces many challenges. But to their credit, they do one thing right: no political parties! Instead of endless verbal sparring over party problems, Tuvaluans have a unicameral government with no political parties. Their 15-person parliament is re-elected every four years by the nation’s citizens. Then, that group elects a Prime Minister and a Cabinet. But there are no parties to cling to in Tuvalu. The country outlaws formal political factions.

Instead, politics there are based on an individual leader’s perspective and personality. Of course, politicians do come together for informal alliances while governing. But these groups are malleable based on each issue. Political scientists have found many different variables that affect how the government gets things done on the islands.

Consensus is emphasized among Tuvalu’s political leaders. Historically, compromise has proven critical to community success. And with a tight-knit group governing such a small population, it makes sense that decorum and cooperation matter. That’s not to say there aren’t issues, though. Traditional gender roles in Tuvaluan culture have left women far underrepresented in politics. Observers hope that will change as Tuvaluan society continues to embrace modernity. For now, politicians of all stripes grapple with serious challenges ahead for this beautiful but isolated island nation.[10]

[ad_2]

Source link