[ad_1]

As a rather commercially successful author once wrote, “the night is dark and full of terrors, the day bright and beautiful and full of hope.” It’s fitting imagery for AI, which like all tech has its upsides and downsides.

Art-generating models like Stable Diffusion, for instance, have led to incredible outpourings of creativity, powering apps and even entirely new business models. On the other hand, its open source nature lets bad actors to use it to create deepfakes at scale — all while artists protest that it’s profiting off of their work.

What’s on deck for AI in 2023? Will regulation rein in the worst of what AI brings, or are the floodgates open? Will powerful, transformative new forms of AI emerge, a la ChatGPT, disrupt industries once thought safe from automation?

Expect more (problematic) art-generating AI apps

With the success of Lensa, the AI-powered selfie app from Prisma Labs that went viral, you can expect a lot of me-too apps along these lines. And expect them to also be capable of being tricked into creating NSFW images, and to disproportionately sexualize and alter the appearance of women.

Maximilian Gahntz, a senior policy researcher at the Mozilla Foundation, said he expected integration of generative AI into consumer tech will amplify the effects of such systems, both the good and the bad.

Stable Diffusion, for example, was fed billions of images from the internet until it “learned” to associate certain words and concepts with certain imagery. Text-generating models have routinely been easily tricked into espousing offensive views or producing misleading content.

Mike Cook, a member of the Knives and Paintbrushes open research group, agrees with Gahntz that generative AI will continue to prove a major — and problematic — force for change. But he thinks that 2023 has to be the year that generative AI “finally puts its money where its mouth is.”

Prompt by TechCrunch, model by Stability AI, generated in the free tool Dream Studio.

“It’s not enough to motivate a community of specialists [to create new tech] — for technology to become a long-term part of our lives, it has to either make someone a lot of money, or have a meaningful impact on the daily lives of the general public,” Cook said. “So I predict we’ll see a serious push to make generative AI actually achieve one of these two things, with mixed success.”

Artists lead the effort to opt out of data sets

DeviantArt released an AI art generator built on Stable Diffusion and fine-tuned on artwork from the DeviantArt community. The art generator was met with loud disapproval from DeviantArt’s longtime denizens, who criticized the platform’s lack of transparency in using their uploaded art to train the system.

The creators of the most popular systems — OpenAI and Stability AI — say that they’ve taken steps to limit the amount of harmful content their systems produce. But judging by many of the generations on social media, it’s clear that there’s work to be done.

“The data sets require active curation to address these problems and should be subjected to significant scrutiny, including from communities that tend to get the short end of the stick,” Gahntz said, comparing the process to ongoing controversies over content moderation in social media.

Stability AI, which is largely funding the development of Stable Diffusion, recently bowed to public pressure, signaling that it would allow artists to opt out of the data set used to train the next-generation Stable Diffusion model. Through the website HaveIBeenTrained.com, rightsholders will be able to request opt-outs before training begins in a few weeks’ time.

OpenAI offers no such opt-out mechanism, instead preferring to partner with organizations like Shutterstock to license portions of their image galleries. But given the legal and sheer publicity headwinds it faces alongside Stability AI, it’s likely only a matter of time before it follows suit.

The courts may ultimately force its hand. In the U.S. Microsoft, GitHub and OpenAI are being sued in a class action lawsuit that accuses them of violating copyright law by letting Copilot, GitHub’s service that intelligently suggests lines of code, regurgitate sections of licensed code without providing credit.

Perhaps anticipating the legal challenge, GitHub recently added settings to prevent public code from showing up in Copilot’s suggestions and plans to introduce a feature that will reference the source of code suggestions. But they’re imperfect measures. In at least one instance, the filter setting caused Copilot to emit large chunks of copyrighted code including all attribution and license text.

Expect to see criticism ramp up in the coming year, particularly as the U.K. mulls over rules that would that would remove the requirement that systems trained through public data be used strictly non-commercially.

Open source and decentralized efforts will continue to grow

2022 saw a handful of AI companies dominate the stage, primarily OpenAI and Stability AI. But the pendulum may swing back towards open source in 2023 as the ability to build new systems moves beyond “resource-rich and powerful AI labs,” as Gahntz put it.

A community approach may lead to more scrutiny of systems as they are being built and deployed, he said: “If models are open and if data sets are open, that’ll enable much more of the critical research that has pointed to a lot of the flaws and harms linked to generative AI and that’s often been far too difficult to conduct.”

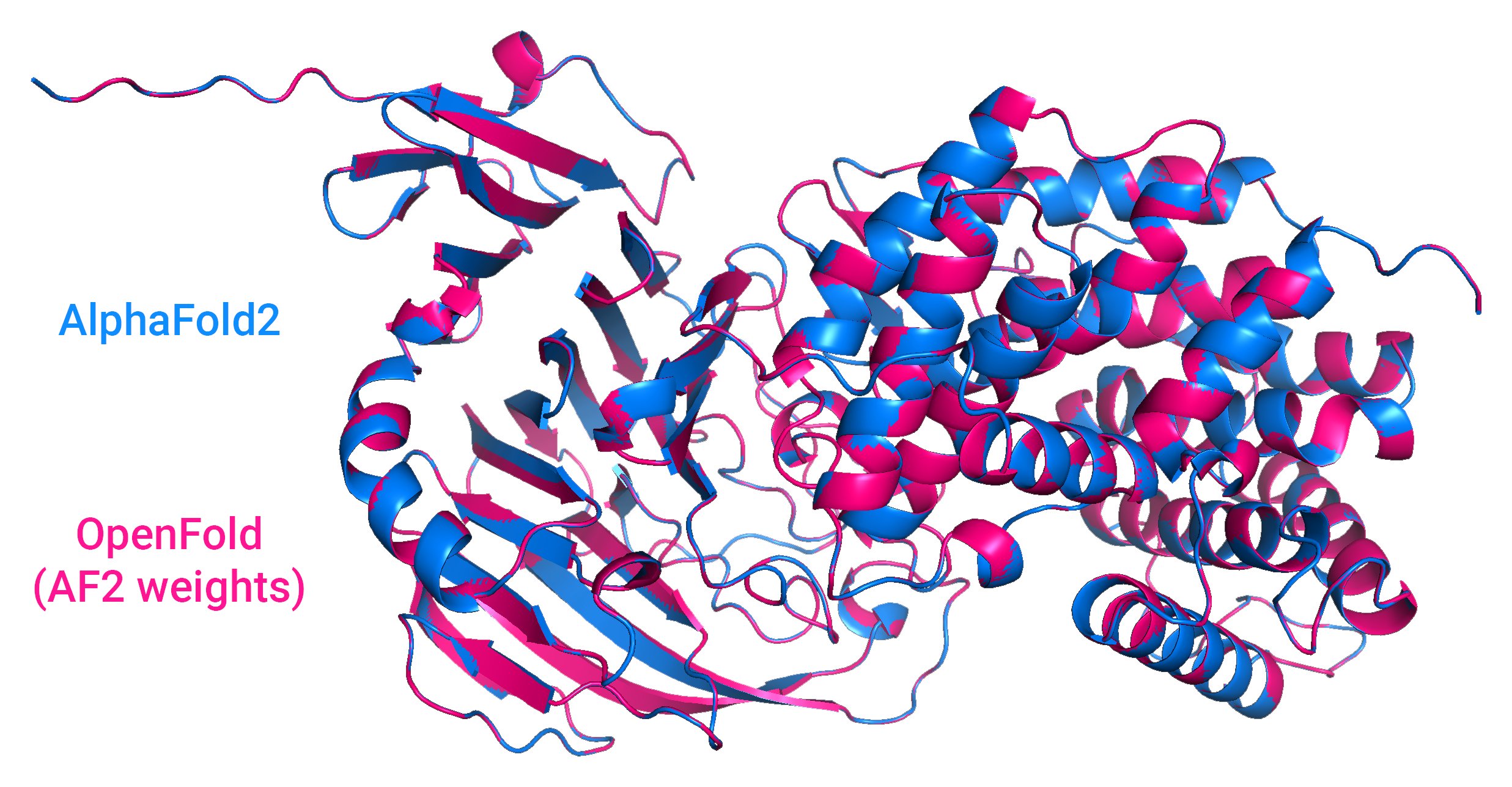

Image Credits: Results from OpenFold, an open source AI system that predicts the shapes of proteins, compared to DeepMind’s AlphaFold2.

Examples of such community-focused efforts include large language models from EleutherAI and BigScience, an effort backed by AI startup Hugging Face. Stability AI is funding a number of communities itself, like the music-generation-focused Harmonai and OpenBioML, a loose collection of biotech experiments.

Money and expertise are still required to train and run sophisticated AI models, but decentralized computing may challenge traditional data centers as open source efforts mature.

BigScience took a step toward enabling decentralized development with the recent release of the open source Petals project. Petals lets people contribute their compute power, similar to Folding@home, to run large AI language models that would normally require an high-end GPU or server.

“Modern generative models are computationally expensive to train and run. Some back-of-the-envelope estimates put daily ChatGPT expenditure to around $3 million,” Chandra Bhagavatula, a senior research scientist at the Allen Institute for AI, said via email. “To make this commercially viable and accessible more widely, it will be important to address this.”

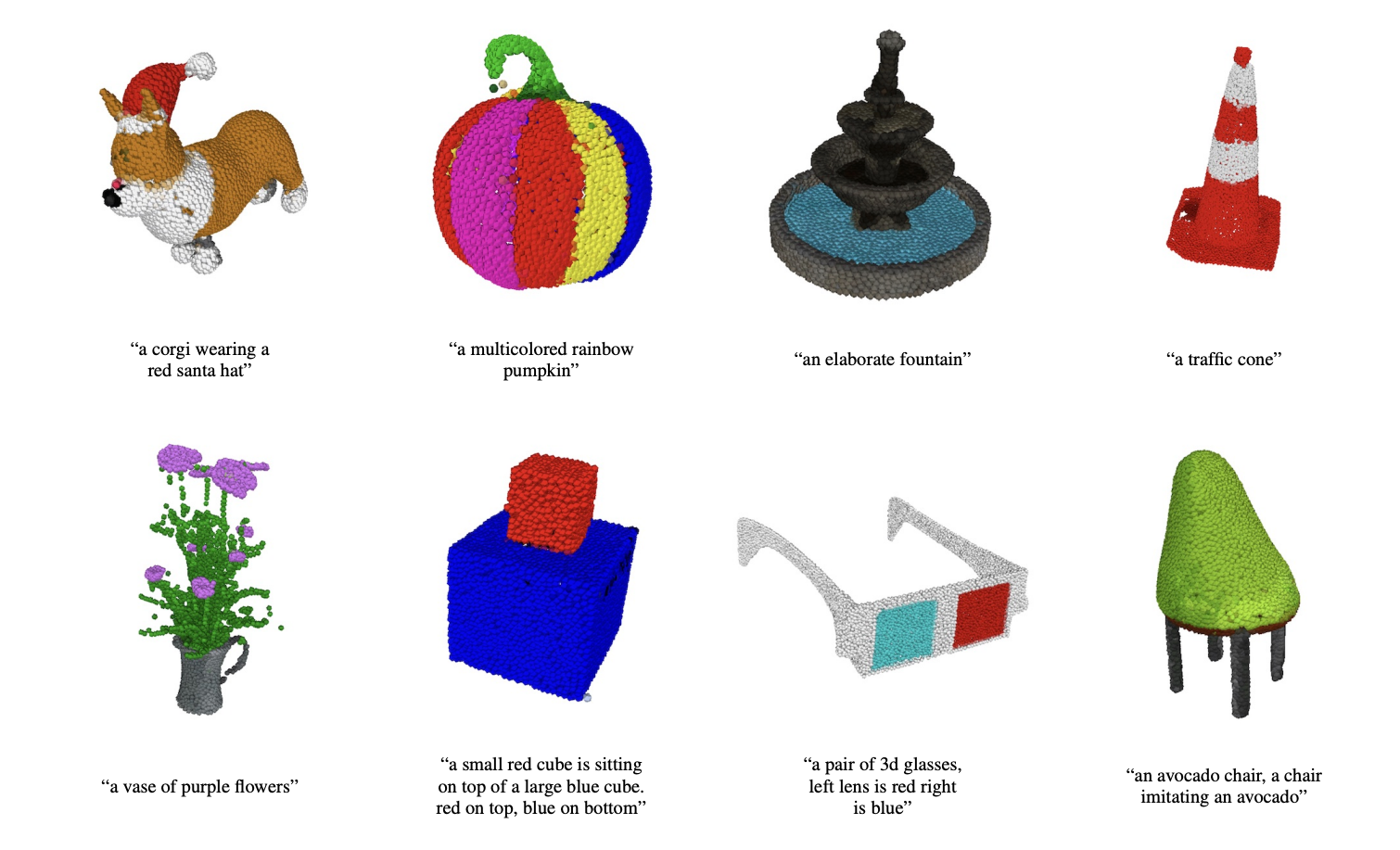

Chandra points out, however, that that large labs will continue to have competitive advantages as long as the methods and data remain proprietary. In a recent example, OpenAI released Point-E, a model that can generate 3D objects given a text prompt. But while OpenAI open sourced the model, it didn’t disclose the sources of Point-E’s training data or release that data.

Point-E generates point clouds.

“I do think the open source efforts and decentralization efforts are absolutely worthwhile and are to the benefit of a larger number of researchers, practitioners and users,” Chandra said. “However, despite being open-sourced, the best models are still inaccessible to a large number of researchers and practitioners due to their resource constraints.”

AI companies buckle down for incoming regulations

Regulation like the EU’s AI Act may change how companies develop and deploy AI systems moving forward. So could more local efforts like New York City’s AI hiring statute, which requires that AI and algorithm-based tech for recruiting, hiring or promotion be audited for bias before being used.

Chandra sees these regulations as necessary especially in light of generative AI’s increasingly apparent technical flaws, like its tendency to spout factually wrong info.

“This makes generative AI difficult to apply for many areas where mistakes can have very high costs — e.g. healthcare. In addition, the ease of generating incorrect information creates challenges surrounding misinformation and disinformation,” she said. “[And yet] AI systems are already making decisions loaded with moral and ethical implications.”

Next year will only bring the threat of regulation, though — expect much more quibbling over rules and court cases before anyone gets fined or charged. But companies may still jockey for position in the most advantageous categories of upcoming laws, like the AI Act’s risk categories.

The rule as currently written divides AI systems into one of four risk categories, each with varying requirements and levels of scrutiny. Systems in the highest risk category, “high-risk” AI (e.g. credit scoring algorithms, robotic surgery apps), have to meet certain legal, ethical and technical standards before they’re allowed to enter the European market. The lowest risk category, “minimal or no risk” AI (e.g. spam filters, AI-enabled video games), imposes only transparency obligations like making users aware that they’re interacting with an AI system.

Os Keyes, a Ph.D. Candidate at the University of Washington, expressed worry that companies will aim for the lowest risk level in order to minimize their own responsibilities and visibility to regulators.

“That concern aside, [the AI Act] really the most positive thing I see on the table,” they said. “I haven’t seen much of anything out of Congress.”

But investments aren’t a sure thing

Gahntz argues that, even if an AI system works well enough for most people but is deeply harmful to some, there’s “still a lot of homework left” before a company should make it widely available. “There’s also a business case for all this. If your model generates a lot of messed up stuff, consumers aren’t going to like it,” he added. “But obviously this is also about fairness.”

It’s unclear whether companies will be persuaded by that argument going into next year, particularly as investors seem eager to put their money beyond any promising generative AI.

In the midst of the Stable Diffusion controversies, Stability AI raised $101 million at an over-$1 billion valuation from prominent backers including Coatue and Lightspeed Venture Partners. OpenAI is said to be valued at $20 billion as it enters advanced talks to raise more funding from Microsoft. (Microsoft previously invested $1 billion in OpenAI in 2019.)

Of course, those could be exceptions to the rule.

Image Credits: Jasper

Outside of self-driving companies Cruise, Wayve and WeRide and robotics firm MegaRobo, the top-performing AI firms in terms of money raised this year were software-based, according to Crunchbase. Contentsquare, which sells a service that provides AI-driven recommendations for web content, closed a $600 million round in July. Uniphore, which sells software for “conversational analytics” (think call center metrics) and conversational assistants, landed $400 million in February. Meanwhile, Highspot, whose AI-powered platform provides sales reps and marketers with real-time and data-driven recommendations, nabbed $248 million in January.

Investors may well chase safer bets like automating analysis of customer complaints or generating sales leads, even if these aren’t as “sexy” as generative AI. That’s not to suggest there won’t be big attention-grabbing investments, but they’ll be reserved for players with clout.

[ad_2]

Source link