[ad_1]

The first lab-grown burger—grown from animal cells in petri dishes, without the animal—was unveiled in the Netherlands nearly a decade ago. Since then, it has helped spawn a growing number of startups racing to bring animal-free “real” meat to the market. But it still isn’t possible to buy so-called cultivated meat in a grocery store; if you want to try cultivated chicken, you have to go to Singapore or an experimental restaurant at a cultivated meat company in Israel. Now, though, if you live in the U.S., you’re one step closer to finding it on a local menu: Upside Foods, a Bay Area food tech company, just got a nod of approval for its chicken from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

On Wednesday, the FDA issued a “no questions” letter, meaning that it accepts the company’s conclusion that the food is safe to eat. “This is a big moment for the future of food,” says Upside COO Amy Chen. It’s a long time coming: The company started meeting with the agency four years ago and discussing how to evaluate a brand-new type of food before the FDA even looked at the company’s safety data. The U.S. doesn’t have a formal approval process for food, so the consultation was voluntary. Still, the food has to be safe under U.S. law and the company wanted to do everything possible to assure the public that it had been vetted. The process was detailed and time-consuming, as the agency reviewed reams of data about the company’s production processes, from how it makes cell lines to how it controls manufacturing.

Upside’s first production facility, a 53,000-square-foot space in Emeryville, CA, is already ready to begin churning out meat in large tanks that look like what you’d see at a brewery. But it will have to pass two more hurdles. Next, the USDA will have to inspect the factory, in the same way that it inspects slaughterhouses now. The USDA will also have to inspect the meat itself. While it’s not possible to predict exactly how long the process will take, it could be a matter of months. The FDA letter was the biggest step, Chen says.

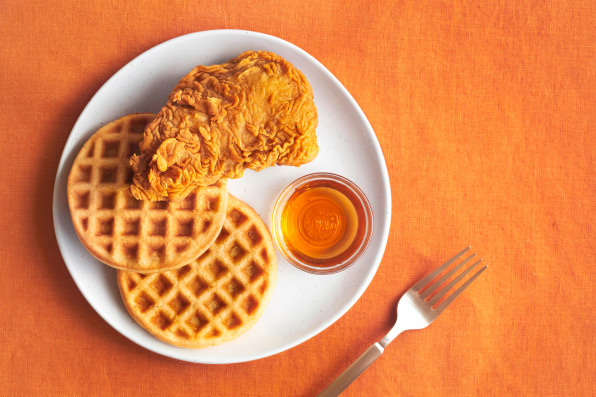

The company plans to launch its chicken first in restaurants, the same strategy taken by plant-based meat pioneers like Impossible Foods, partly so that it can control the experience for consumers trying it for the first time.

It’s also working on other products, from duck and beef to lobsters and scallops. “What’s unique about our approach is that we have designed it to be more universal from the start, thinking a bit more around what would it take to transfer across species,” says Chen. They plan to eventually make a full range of meat products.

The company hasn’t shared the cost of the chicken yet, but it will be sold at a premium, with the goal to eventually reach price parity. “Ultimately, to have the impact that we want to have in the world, we need to get to a level of scale and cost that is competitive with conventional meat,” she says.

The team is working on ways to bring down the cost now, including finding ways to making production more efficient and working closely with suppliers. “The supply chain components that we need right now—things like amino acids or vitamins—don’t exist at the scale that we need for the industry to be successful and have an impact on the world,” she says. “But that doesn’t mean that they can’t. There’s just a lot of infrastructure building work that is required.”

[ad_2]

Source link