[ad_1]

Mohammad Hashim, a former officer in the Afghan National Army, now picks apples for a living.

Claire Harbage/NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Claire Harbage/NPR

Mohammad Hashim, a former officer in the Afghan National Army, now picks apples for a living.

Claire Harbage/NPR

MAIDAN SHAHR, Afghanistan — When Mohammad Hashim enlisted in the Afghan National Army, he never imagined his career would land him in an apple orchard.

Just a couple of years ago, the former army officer was in charge of setting up military checkpoints in Helmand Province, where some of the fiercest fighting between Taliban insurgents and Afghan forces took place. Now, he picks apples for a living.

“There’s no work for those of us who served in the military,” says Hashim as he carefully unwraps a black-and-white checkered scarf revealing a pile of military training certificates. “As you can see, I’m educated and experienced, but this is the best I can find to support my family.”

When the Afghan republic collapsed last year, so too did its U.S.-backed military. Mohammad Hashim, like tens of thousands of Afghan soldiers, lost his job.

Claire Harbage/NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Claire Harbage/NPR

When the Afghan republic collapsed last year, so too did its U.S.-backed military. Mohammad Hashim, like tens of thousands of Afghan soldiers, lost his job.

Claire Harbage/NPR

When the Afghan republic collapsed last year, so too did its U.S.-backed military. Overnight, tens of thousands of Afghan soldiers lost their jobs and suddenly found themselves living under the thumb of those they spent two decades fighting.

Ever since, life has radically changed for them. Those who once drove tanks now drive taxis. The soldiers who once stood in formation now stand in line for food aid. Some former soldiers who served during the old republic tell NPR they live in fear of being detained and disappeared.

Near the orchard, Mohammad Hashim walks past buildings that show signs of damage from the war.

Claire Harbage/NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Claire Harbage/NPR

Near the orchard, Mohammad Hashim walks past buildings that show signs of damage from the war.

Claire Harbage/NPR

That fear, and the heckling from Taliban who learned of Hashim’s military service, are what led him to pay smugglers to get his younger brother — also a former military officer — across the border to neighboring Iran.

Four days after his brother left in October, Hashim was still not sure of his whereabouts. “We don’t know if he’s still on his way, if he got there, no idea,” says Hashim, who can’t yet afford the same escape with his wife and three young daughters.

And so he works, from dawn until dusk, a prisoner of his past.

“I don’t have one good memory of the war,” says the 29-year-old. “I want to forget everything.”

Mohammad Hashim stands under a tree at the apple orchard where he works.

Claire Harbage/NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Claire Harbage/NPR

Mohammad Hashim stands under a tree at the apple orchard where he works.

Claire Harbage/NPR

But the memories are impossible to escape. Just beyond the apple grove, crooked sticks poke out of the earth carrying tattered white flags, marking the graves of fallen Taliban insurgents. Hashim’s boss’ mud brick home, long caught in the crossfire, has fallen into disrepair. Massive potholes from roadside bombs dot the main highway leading to this orchard. The war still casts a dark shadow over Hashim’s life.

An ex-commando goes into hiding

Soon after the Taliban raised their flag over Kabul in August 2021, the movement’s leaders declared a general amnesty for all citizens, including those who served the previous government. “We are assuring the safety of all those who have worked with the United States and allied forces,” said Taliban spokesman Zabihullah Mujahid two days after the capital fell.

A fallen apple sits in the shadow of a tree at the orchard where Hashim works, not far from the graves of Taliban insurgents.

Claire Harbage/NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Claire Harbage/NPR

A fallen apple sits in the shadow of a tree at the orchard where Hashim works, not far from the graves of Taliban insurgents.

Claire Harbage/NPR

After allegations of revenge killings emerged, the country’s acting Defense Minister Mullah Mohammad Yaqoob reinforced Mujahid’s message, ordering members of the Taliban not to seek revenge on any citizen. Still, the United Nations Mission in Afghanistan has alleged more than 400 cases of extrajudicial killings or detentions of former Afghan National Defense and Security Forces in the first six months of Taliban rule.

Watchdog groups and analysts say the leadership’s directives are either not reaching Taliban rank and file, particularly in more remote villages — or worse yet, are ignored altogether.

“What we’re seeing is that while they’re making these proclamations from the central government, they’re not really enforced at any meaningful level outside the central rings of power,” says Chris Purdy, a director at Human Rights First. “They pretty much leave the actual decision-making up to their local commanders.”

What’s also clear is that setting up a system of governance after 20 years of war hasn’t come easily for the new government.

“For the 20 years the Taliban were engaged in war, there was not much difference between top commanders and foot soldiers,” says Nasratullah Haqpal, a Kabul-based political analyst. “They were sitting at the same tables, sleeping in the same rooms, and seen as equals and there wasn’t really a hierarchy. So now, when the top leadership says something, lower rank and file don’t always follow them or care.”

The fear of getting caught up in this discrepancy has sent many former members of the elite Afghan special forces into hiding.

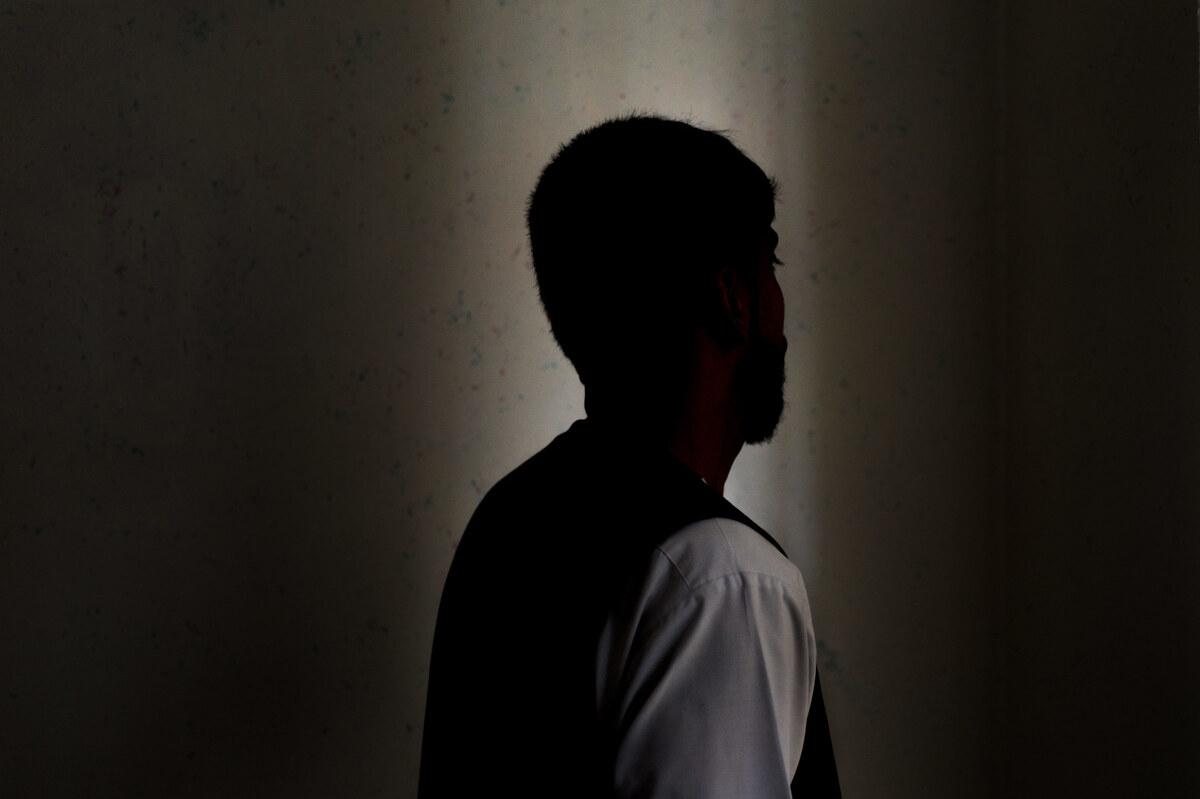

One former commando who asks not to be identified because he still fears for his own safety, and his family’s, tells NPR he never lingers in any one location for more than a day, afraid he’ll be tracked down and detained. He suspects this is what has happened to several others with whom he served but can no longer reach.

One former commando who asks not to be identified because he still fears for his own safety, set his uniforms and documents on fire last year as the Taliban closed in on Kabul and has been in hiding ever since.

Claire Harbage/NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Claire Harbage/NPR

One former commando who asks not to be identified because he still fears for his own safety, set his uniforms and documents on fire last year as the Taliban closed in on Kabul and has been in hiding ever since.

Claire Harbage/NPR

He says he received a phone call seven months ago from a man who identified himself as a Taliban commander asking him to join their ranks. He hung up and immediately changed his number.

“I can’t believe them,” says the 27-year-old, skeptical that followers of this new government would be willing to “forget the many high-ranking Taliban insurgents Afghan special forces eliminated over the years.”

Few ways out

Like many Afghan veterans of the 20-year war, the commando is desperate to find a way out of the country but has few options.

Despite spending years working shoulder-to-shoulder with U.S. forces, he can’t qualify for a special immigrant visa.

“I was paid by the old Afghan government and I don’t have the HR letter I need to get the special immigrant visa,” he says.

He feels frustrated that the State Department will only accept a U.S.-issued human resources letter. “That’s the problem many of my friends and soldiers face,” he says.

A prayer rug sits on a window sill in a location where the ex-commando sometimes stays.

Claire Harbage/NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Claire Harbage/NPR

A prayer rug sits on a window sill in a location where the ex-commando sometimes stays.

Claire Harbage/NPR

They all have recommendation letters from supervisors and American counterparts, he says, but the salaries they earned from the previous Afghan government are costing them a pathway out.

Refugee and immigrant advocates are urging the State Department to broaden its qualifications and expedite its approval process, arguing that even when the application process works as intended, it can take years for an approval.

“The requirements of the program are very rigid and Afghans have been killed while waiting for visas to be issued,” says Adam Bates, supervisory policy counsel at the International Refugee Assistance Project, who notes his organization would not exist “if the SIV program functioned efficiently and if not for just the sheer amount of erroneous denials of people and documents being submitted.”

Getting to a neighboring country to obtain refugee status is also fraught with risks.

“If they did not have passports before the government fell, getting one now is very dangerous and sometimes deadly if you or anyone in your family was ever associated with Americans,” says Kendyl Noah, a former U.S. Army medic who worked with the commando during her deployment. “Nearby countries either stopped accepting Afghans or are blatantly hostile to Afghans, arresting them, beating them, throwing them back over the border or sometimes handing them to the Taliban directly.”

The State Department doesn’t dispute the hazards.

“We recognize that it is currently extremely difficult for Afghans to obtain a visa to a third country or find a way to enter a third country and may face significant challenges to fleeing to safety,” a State Department spokesman said in an email to NPR, adding that the department has increased resources to process visas more expeditiously. “We also particularly urge states to uphold their respective obligations to not return Afghan refugees or asylum seekers to persecution or torture.”

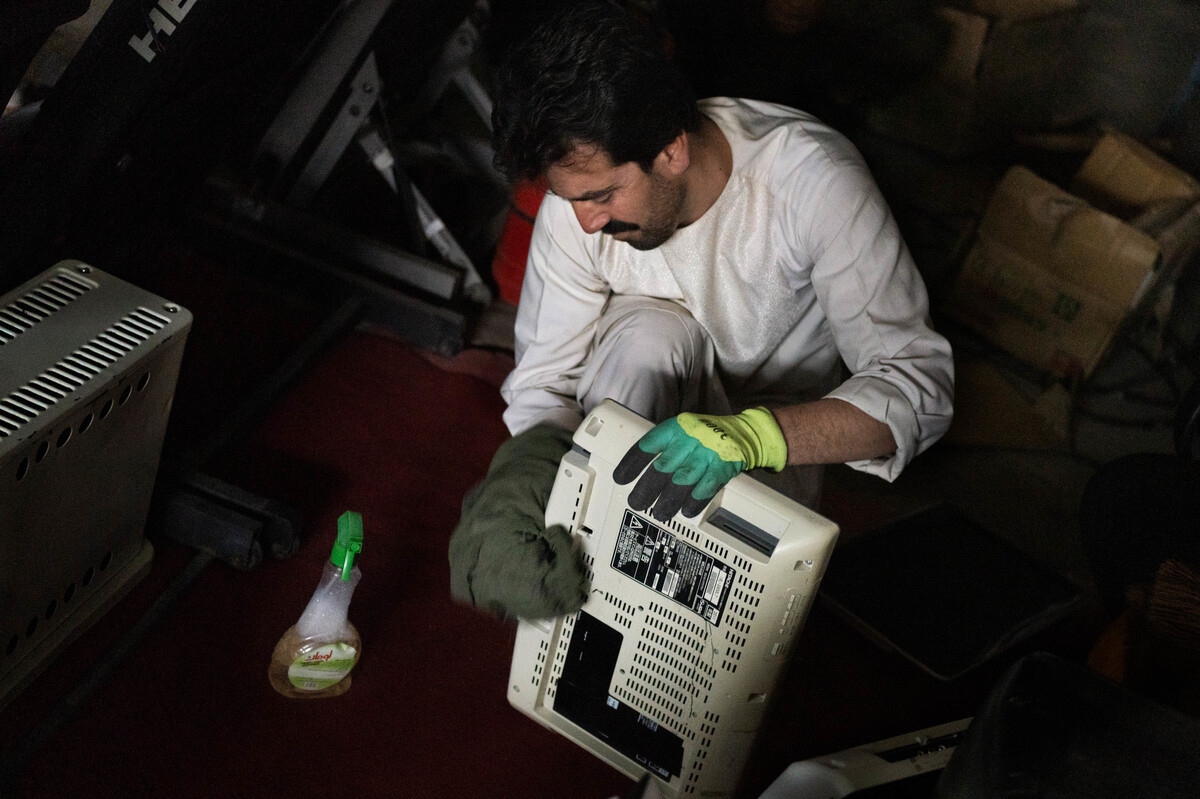

Siraj Zamanzai cleans used electronics at a shop. He was unemployed for a year before finding this job.

Claire Harbage/NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Claire Harbage/NPR

Siraj Zamanzai cleans used electronics at a shop. He was unemployed for a year before finding this job.

Claire Harbage/NPR

With few ways out, advocates and analysts worry about where former members of this former fighting force may turn if they are indefinitely unemployed and ostracized.

The commando says other Afghan military veterans have contacted him with information on how to join Russia’s military. They escaped to Iran and were recruited there, but he says it’s out of the question for him.

“I will never join a force that’s working against America,” he says, acknowledging that others who have families to support may not be in a position to turn down the proposition.

“That Afghans would find themselves taking salaries to work on the side of a country that invaded them in the ’80s and committed terrible atrocities — the working calculus is going to be ‘How do I feed my family and how do I survive,'” says Douglas London, ex-CIA chief of counter-terrorism for South and Southwest Asia. “It is in the interest of our national security to try to mitigate against the risk of these folks working for adversaries.“

Some in menial jobs consider themselves lucky

On the outskirts of Kabul, 36-year-old Siraj Zamanzai is trying to make the best of his new life.

Siraj Zamanzai says he considers himself among the lucky ones, as his income allows him to help his family.

Claire Harbage/NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Claire Harbage/NPR

Siraj Zamanzai says he considers himself among the lucky ones, as his income allows him to help his family.

Claire Harbage/NPR

After a year of unemployment, the former army captain recently found a job as a shopkeeper’s assistant at a secondhand store, where he earns $3 a day unboxing used appliances imported from Japan.

Even though Afghan troops were often not paid on time and the size and strength of the fighting force was frequently overstated by U.S. and Afghan officials, it was work that Zamanzai took great pride in for the 12 years he served.

“We were valuable people who made a lot of sacrifices to serve our country, and now look at us — look at me,” he says.

But that’s as far as his criticisms go.

He treads carefully talking about the Taliban, focusing on how “both sides lost too many martyrs in the war.” He casts doubt on allegations of Taliban mistreatment that he says he “must see for himself to believe.”

Zamanzai considers himself among the lucky ones.

“At least I’m in a position to help my family survive,” he says at the start of his 12-hour work day. “So many other families lost their fathers or husbands in the war and are out there begging on the streets.”

[ad_2]

Source link