[ad_1]

This article was adapted from the MidRange newsletter, which is publishing tips on the Mastodon social media network in a pop-up newsletter format called How-To Mastodon.

There is a clear need right now for focused, simple information on Mastodon, a long-running decentralized open-source application that ties into the ActivityPub protocol that suddenly is looking very attractive thanks to the wild shifts happening at Twitter.

It is exciting that this application has finally found a mainstream audience. But its creators and fans were not expecting the influx to the level it has emerged, and you can tell this just from the crunch on some of the servers. (On Saturday night, I was getting notifications about replies that were sent six hours prior.)

People are trying to figure out this new, slowly emerging network in real time, and while I can’t say that I know everything about it, I did sign up for it almost at the beginning and have been trying to keep an eye on its evolution in the more than half-decade since. So with the Fediverse scaling up in real time, here are some lessons and starting points that could help you understand how this crazy machine works.

So, let’s get started.

Thoughts on self-serve ownership, onboarding, and how it shaped the list of Mastodon servers

Everyone who has turned the switch on a Mastodon server made a choice. They decided to run a server, and running a server is generally considered a complex thing to do. But the nice thing about a decision like this is that anyone can make it for themselves.

The problem is, the types of people who run servers generally have different interests from the broader public. As a result, when a mass of new users began to sign up for a Mastodon account, they ran directly into a swarm of servers that seemed poorly optimized for personal interests. Prestige TV fans, hiking enthusiasts, and Swifties found no communities focused on their interests, but if you’re into Ruby or FOSS or STEM or retro tech, server owners on Mastodon already had you covered. When people who know how to run a server self-select, this is what happens.

This has had an effect on the onboarding experience, and led to some dissenting feedback on its uptake. While I can’t predict the future, I have a feeling that the developers of the open-source Mastodon application might see this moment as an opportunity to broaden its approach.

Mastodon, which is based on the open protocol ActivityPub, will likely see effort being put into simplifying the onboarding experience and figuring out ways to simply offer some of the most common community types itself. Word is that version 4 of the service, which is in release candidate mode, will help with this.

But I think some clever positioning of the servers could help, too. If everyone was given six narrow-but-general communities to join on top of the user-generated ones—say music, movies, technology, politics, business, and sports—most of the complaints about onboarding would be nullified. Heck, even calling them something other than instances or servers would be a huge kick in the pants.(Compare this to how early online communities like GeoCities worked and you can see the parallels.)

I think that as Mastodon gets a more mainstream audience, we’ll see the process of spinning up a Mastodon server get easier. The third-party hosting service Masto.host was flooded with demand over the weekend, clearly showing that people want to take part. If it keeps up, general-interest cloud hosting companies like Vultr and DigitalOcean will probably start promoting one-click Mastodon installs, for example, as they do for Ghost, Minecraft, and WordPress.

But for folks who find this state of affairs confusing, yes, it is. But historically, social communities have looked much more like Mastodon than they have Twitter. Usenet was built in exactly the same way. So was Yahoo! Chat, ICQ, and IRC. Twitter’s main innovation, in many ways, is that it combines all of these people into one giant public feed and lets users find their people, building interesting conversations from the collisions that this unusual state of affairs created. Eventually algorithms helped with this, but they also made people more comfortable with those contours, and Twitter was only taking steps to resolve this with groups.

The reason Mastodon is great is because it makes room for both experiences—the narrow community and the outside world—in one platform. The local timeline is the narrow community; the federated timeline is the outside world. You can choose which one to focus on. (Of course, some Twitter expats have made pretty fair arguments about the fact that we have wide interests that may not fit one server. Hashtags, which are even more valuable on Mastodon than Twitter, are one way to get around this.)

Will that be enough to convince some folks that Mastodon is not, in fact, hopelessly complex? Probably not. But I do think Mastodon users should be open with feedback right now—because developers and server admins will hear it. Already we’re seeing high-profile figures like Taylor Lorenz offering reasonable cases for search capabilities and quote tweets to be expanded that have been put to the side in the past—and odds are, we may see some changes as the community grows and interest in alternative options appears.

After all, the project is built for the users, not the bottom line.

A few server-choosing suggestions

- Understand the balance between small and large servers. Small servers tend to be more narrowly focused from a subject matter standpoint but can access much of what’s happening throughout the network; large servers tend to be more general, and more congested. It might feel a little like Twitter in 2009 or IRC in 1997.

- Have a large fanbase? Be careful where you land. A single user with thousands of followers can have an outsize effect on a server’s load, so consider giving a shout before you move onto a given server. And consider chipping in for the hosting bill if the owner has a Patreon or similar link up for it.

- Consider trust and safety. You may or may not know the person operating the server, and that can lead to concerns about trust. As Eugen Rochko recommended all the way back in 2017, do some research into the rules of any server you join before making an account, and consider what you say publicly or privately on the service. And don’t forget about two-factor authentication; security matters more than ever.

The power of alt text, something that matters a lot on Mastodon

A few weeks ago, a Twitter user called me out on a mistake that a lot of users make. That is, they forget the alt-text on images and videos they upload.

It is an easy thing to miss, but too many don’t take the step to do it because they favor immediacy over accessibility.

I had been getting better at doing it, but once I got the nudge and explainer, I got with the program and have been alt-texting all the things.

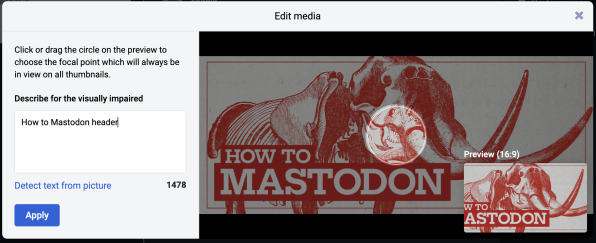

Mastodon, which has built a reputation for putting accessibility first, makes this a lot easier than other platforms, in part because of a tool that Twitter’s default applications do not offer: the ability to detect text in an image and use that as the alt text. Given that screenshots are a hugely popular way for people to share longer thoughts on social media, this tool is a huge help.

But if you need a nudge, there’s a bot on Mastodon that can lightly scold you if you fail to add alt text to your images. And if you need some tips on how to write accessible text, this guide from WebAIM offers an excellent starting point.

Links and stuff

» Hoping to crosspost between Twitter and Mastodon? There are a couple of great options out there, including the Mastodon Twitter Crossposter, and Moa Bridge. Both of these tools work roughly the same, and allow you to post things only when certain parameters are set—and in the case of Mastodon Twitter Crossposter, you can filter out specific words, in case your Twitter followers are sick of hearing you talk about Mastodon.

» If you’re a newshound looking for reporters to follow, there are a few vetted lists going around, including this Google doc with more than 550 entries as of this writing, and this Github doc should scratch a similar itch. An instance to watch is Journa.Host, run by Adam Davidson, formerly of The New Yorker.

» In case you want an alternate, simplified version of the Mastodon user interface, a good option is Pinafore.

[ad_2]

Source link