[ad_1]

Afghan Special Immigrant Visa applicants crowd into the Herat Kabul Internet cafe, seeking help applying for the SIV program on Aug. 8, 2021, in Kabul, Afghanistan. The Taliban took over Afghanistan a week later. More than 74,000 applicants remain in the backlog of the SIV program, designed to help those who served the U.S. overseas.

Paula Bronstein/Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

Paula Bronstein/Getty Images

Afghan Special Immigrant Visa applicants crowd into the Herat Kabul Internet cafe, seeking help applying for the SIV program on Aug. 8, 2021, in Kabul, Afghanistan. The Taliban took over Afghanistan a week later. More than 74,000 applicants remain in the backlog of the SIV program, designed to help those who served the U.S. overseas.

Paula Bronstein/Getty Images

Sanaullah worked for two years as a combat interpreter for the U.S. military in Afghanistan — which, even on quiet days, meant risking his life. Almost as soon as he started the job in 2018, Sanaullah says he was watched and followed by the Taliban, and even heard of a plan that same year to kidnap and possibly kill him.

“But by the time they wanted to [carry out the plan] one of the guys who was living in the same building with me informed me,” he says. He escaped by climbing through his apartment window, he says. NPR is only using his first name for security reasons.

Last year, President Biden vowed that Afghans who helped the U.S. military “are not going to be left behind.” But since the U.S. left Afghanistan in August 2021, Sanaullah says he has been living on nothing but “broken promises.”

“I know other people — just business owners — who got evacuated, but … I am still waiting. I can’t understand why, I don’t understand this disconnected process,” he says. “I’m so frustrated and so disappointed. I never thought that something like that could happen.”

He is in hiding after his house was raided by the Taliban four times over the past year.

Thousands of Afghan applicants for Special Immigrant Visas are still awaiting decisions

In the year following the Taliban takeover, tens of thousands of Afghans hoping — and in many cases, needing — to leave for the U.S. have been left in a bureaucratic limbo. Their future is uncertain.

Sanaullah, 23, is one of more than 74,000 applicants stuck in the backlog of the Special Immigrant Visa program, which was designed to help those who served the U.S. overseas. A State Department spokesperson tells NPR that between July 2021 and July 2022, 15,000 SIVs have been issued to principal applicants and eligible family members.

It is not just former military interpreters like Sanaullah who are at risk — activists, journalists, former employees of the previous government and armed forces are all subject to being jailed, beaten and disappeared.

“I wish I could leave. The longer it takes, my life is at higher risk,” says Sanaullah. He’s not hiding in his own hometown because too many people there know that he worked with U.S. troops.

Former Afghan interpreters hold banners during a protest against the U.S. government and NATO in Kabul on April 30, 2021.

Mariam Zuhaib/AP

hide caption

toggle caption

Mariam Zuhaib/AP

Former Afghan interpreters hold banners during a protest against the U.S. government and NATO in Kabul on April 30, 2021.

Mariam Zuhaib/AP

According to the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services agency, over 88,500 Afghans have been resettled in the U.S. since the Taliban returned to power last year, 20 years after their overthrow in 2001. That number represents a combination of different types of visas.

Sanaullah’s SIV application was completed — meaning all the documents were accepted and his application was approved — three months ago. He says his U.S. visa interview has been scheduled for next month at the U.S. Embassy in Islamabad. Visa interviews take place in neighboring Pakistan because the U.S. shut its embassy in Kabul last year.

Now Sanaullah is is trying to secure a visa to Pakistan. He has been scraping money together to pay a $600 agency fee, and hopes he can get to Islamabad in time — and before the Taliban close in on him.

For all the difficulties Sanaullah is facing, he does at least have an Afghan passport — an obstacle that many other Afghans are struggling to overcome. Sanaullah and others say that the only way to get the document in Afghanistan now is by paying bribes to Taliban officials. (NPR was unable to independently confirm reports that bribes can reach up to $2,000. Taliban officials have acknowledged corruption in some passport offices).

And even then, the Afghan passport is considered the worst in the world — making it a struggle to obtain even tourist visas to most countries.

Afghan women are finding it especially hard to leave the country — no matter where their destination is

One female Afghan student, who does not want NPR to use her name because she fears for her safety, has been accepted to study architecture at a university in Malaysia.

Before the Taliban takeover, she was studying journalism. But, she says, she had to let go of her dream of becoming a journalist in her own country because of the Taliban’s de-facto ban on women studying in most universities. So she has shifted her focus to architecture because she thinks she’ll have a better chance of working as an architect in Afghanistan.

“This is the best chance I have,” she says, referring to her latest study plans. “I don’t have another plan B.”

But in September, she suffered another setback. She was told by the Malaysian agency processing her paperwork that her passport, which was valid for another 13 months, needed to be valid for over 18 months in order to receive her study visa.

Afghan women listen to a lesson in an education center in a refugee camp at Holloman Air Force Base in New Mexico on Nov. 4, 2021. The Department of Defense and Department of Homeland Security’s Operation Allies Welcome initiative aims to support and house Afghan refugees as they transition into more permanent housing in the U.S.

Jon Cherry/Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

Jon Cherry/Getty Images

Afghan women listen to a lesson in an education center in a refugee camp at Holloman Air Force Base in New Mexico on Nov. 4, 2021. The Department of Defense and Department of Homeland Security’s Operation Allies Welcome initiative aims to support and house Afghan refugees as they transition into more permanent housing in the U.S.

Jon Cherry/Getty Images

“There’s always, always problems for Afghans,” she says.

She was able to extend the passport she had after asking a family friend to use his connections to help. Now she’s waiting, hoping for her Malaysian visa to be approved. She has already delayed her studies by two years. If she can’t sort out her visa situation, she will lose a third year.

But even with all the correct documentation, some women seeking to leave Afghanistan are being stopped.

In August, some 120 students were in Kabul International Airport about to board a flight to Doha, Qatar. But only the male students were allowed to travel. Taliban authorities held back 60 female students and instructed them to go home.

Among those denied boarding was a 19-year-old student, who does not want to be named because of her history of activism and because she fears her scholarship to study in Doha, Qatar, may be revoked.

“We went to the airport, everything was going normal, and then suddenly, the Taliban came and took our tickets and our passports and they said, ‘You don’t have a male guardian. What are you studying, where are you going?'” she says.

The Taliban photographed the women’s passports and visas. She says that the students were also photographed and filmed.

“They really insulted us. They said, ‘You don’t have any dignity. You are spies for Americans,'” she says.

Backlogs and changing policies

Afghans hoping to reach the U.S. have been able to apply for a variety of visas. The humanitarian parole process also temporarily allows individuals into the U.S. for urgent humanitarian reasons — for Afghans who are overseas or already in the U.S.

But the whole system was put under pressure because of the U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan, with U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, the Department of Homeland Security and the State Department all scrambling to catch up.

Before last summer, USCIS received fewer than 2,000 requests for humanitarian parole visas annually from all nationalities. But between July 1, 2021, and Sept. 1 of this year, the number of applications jumped to more than 49,500 from Afghan nationals alone — 70% of those applications came from people still in Afghanistan. Roughly 9,800 of total applicants have been denied, and 410 Afghan nationals outside the U.S. have been conditionally approved.

Another spokesperson for the State Department tells NPR that staff has been added to U.S. embassies in Qatar, Pakistan and the United Arab Emirates. But the visa pipelines for Afghans remain clogged.

Many immigrant advocacy groups fear the situation could get even tougher for Afghans now.

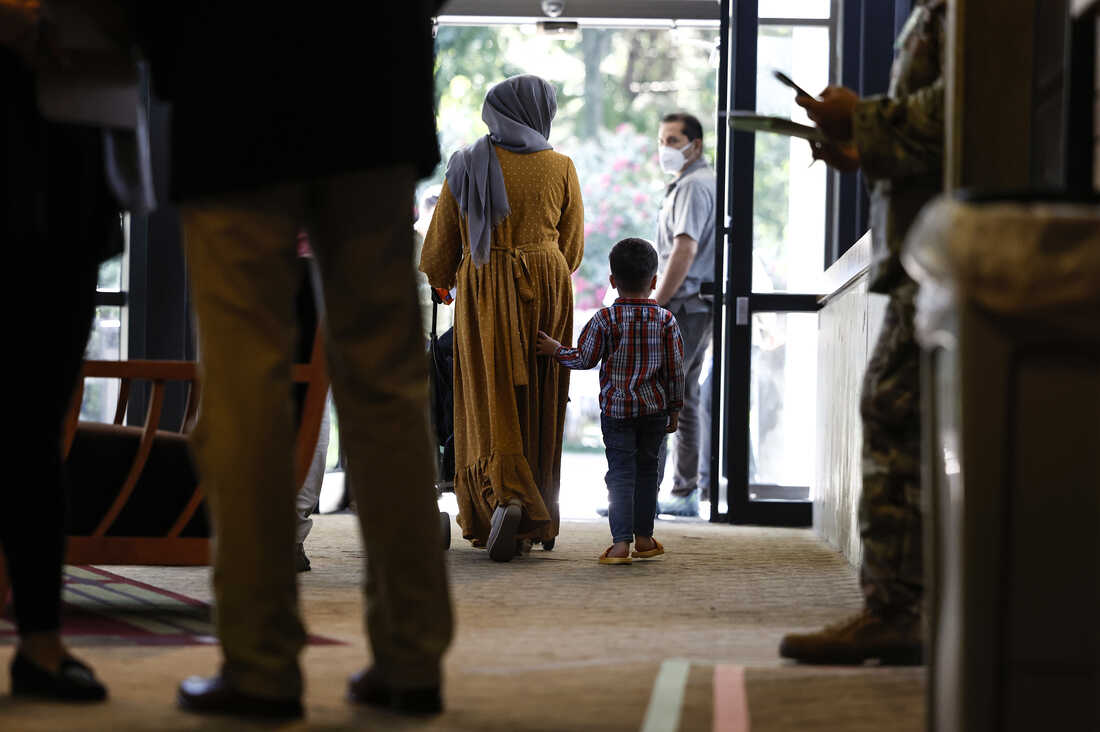

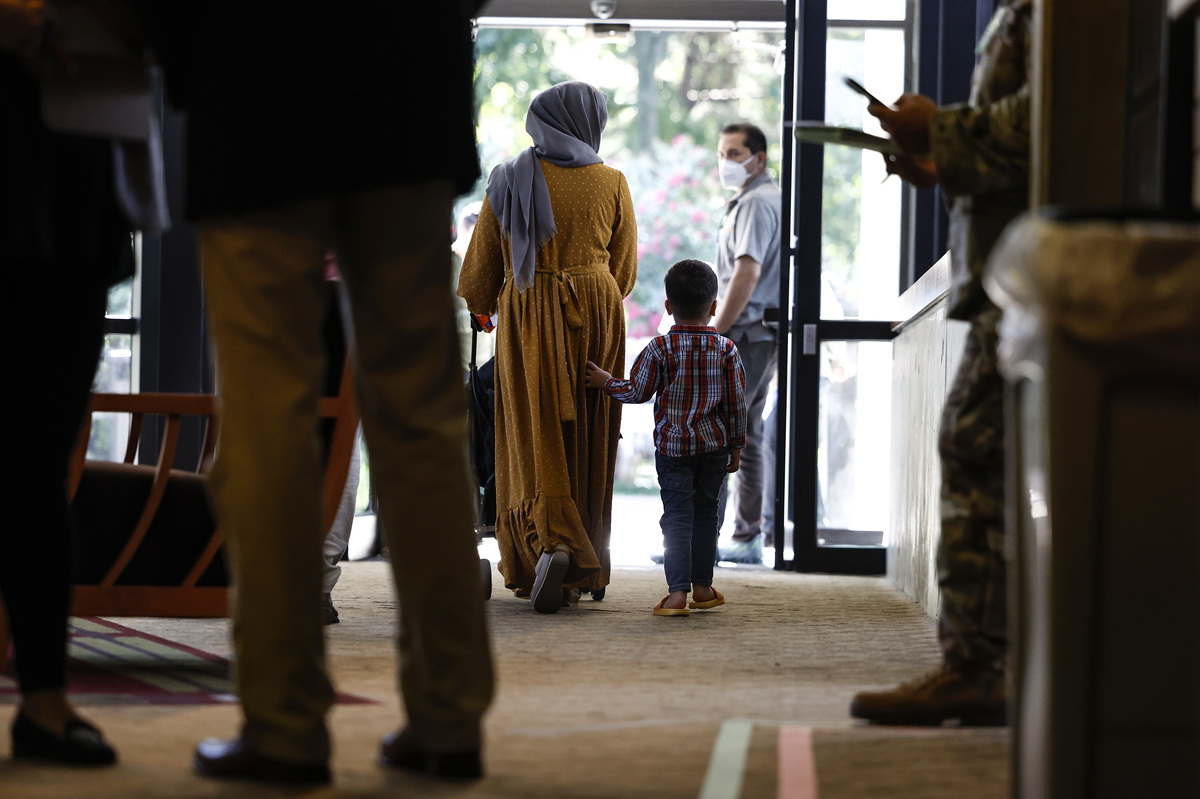

An Afghan woman and her son walk through the National Conference Center, redesigned to temporarily house Afghan nationals, on Aug. 11 in Leesburg, Virginia. Operation Allies Welcome recently turned the NCC into a hotel-like location where Afghan nationals who recently left Afghanistan can begin the process of resettling in the United States.

Anna Moneymaker/Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

Anna Moneymaker/Getty Images

An Afghan woman and her son walk through the National Conference Center, redesigned to temporarily house Afghan nationals, on Aug. 11 in Leesburg, Virginia. Operation Allies Welcome recently turned the NCC into a hotel-like location where Afghan nationals who recently left Afghanistan can begin the process of resettling in the United States.

Anna Moneymaker/Getty Images

Operation Allies Welcome, established to coordinate U.S. government efforts to resettle at-risk Afghan nationals, is ending, and being replaced. “Operation Allies Welcome has been a historic whole-of-society effort to resettle our Afghan allies, in communities across our country. This Operation is made possible by partnerships across numerous federal agencies; state and local governments; non-profit organizations, including faith-based and veterans’ groups; the private sector; and local communities,” a Department of Homeland Security spokesperson said in a statement responding to NPR’s questions about what this change might mean for Afghans who are in the pipeline.

The White House has announced the start of Operation Enduring Welcome, which will support the resettlement of Afghans in the U.S. starting this month, with the new fiscal year. The aim, according to DHS, is to encourage resettlement that is long-term rather than the temporary humanitarian parole.

Up until now, Afghans could be granted humanitarian parole at the port of entry by Homeland Security. Of the 88,500 Afghan nationals who have been resettled in the U.S. over the past year, most of the 77,000 who were granted humanitarian parole entered this way. That will no longer be allowed.

Afghans outside the U.S. — like people from other countries — can still apply to USCIS for humanitarian parole.

Meanwhile, funding for the Afghan Adjustment Act, a bill intended to cut some of the red tape out of the immigration process and ease the way to permanent residency for Afghan evacuees who are already in the U.S., was cut out of the government spending bill that passed on Friday. However, the bill did include $3 billion in aid for Afghan resettlement efforts.

Many Afghans are reaching out to advocacy organizations for advice on how to leave their country. Among those responding to desperate emails and calls is Arash Azizzada, co-director of Afghans for a Better Tomorrow, a diaspora group.

“I try to figure out how to deliver the worst news in the world,” says Azizzada. “That there are 75,000 principal applicants ahead of you. And good luck waiting through years and years of bureaucratic backlog that the American government doesn’t seem interested in fixing.”

Like many others, he has called on the White House to cut red tape, and if the U.S. is not going to reopen the embassy in Kabul, to at least allow consular interviews to happen online — but for now, in-person interviews continue for humanitarian parole applications and SIVs, allowing for the collection of biometric data and fingerprints.

“These barriers have been put up very much on purpose,” says Azizzada. “They aren’t being dismantled or adjusted for Afghans.”

He says he tells Afghans who ask about U.S. promises to stand by them that they have been abandoned.

“I tell them, ‘America lied to you,'” he says. “America is breaking its promise.”

[ad_2]

Source link