[ad_1]

This article will contain spoilers for the ending(s) of the 2018 film “Black Mirror: Bandersnatch.”

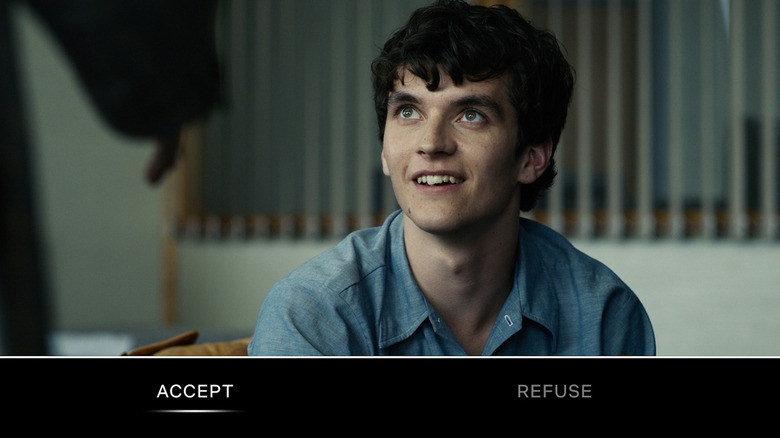

In 2018, director David Slade (Aphex Twin’s “Donkey Rhubarb” music video, “Hard Candy”) and screenwriter Charlie Brooker (co-showrunner of “Black Mirror”) teamed up with Netflix to try out something that hadn’t been attempted too many times in the past. Using a kind of basic “branching video” technology, their “Black Mirror” feature film “Bandersnatch” could be watched as a Choose-Your-Own-Adventure-style interactive experience, letting a viewer decide how the story would progress. About ten minutes of the film would elapse before the main character Stefan (Fionn Whitehead) was faced with a decision, major or minor. On the bottom of the screen, two buttons would appear, and the viewer could dictate Stefan’s choice using their remote control. Fittingly, the plot of the movie involved 1984-era computer programmers attempting to build their very own Choose-Your-Own-Adventure-style video game, based on his late mother’s fictional novel “Bandersnatch.”

Patient viewers who watched through “Bandersnatch” several times, being careful to explore each branch of the narrative, will have been treated to one of multiple endings. Some of the endings are quite grim, with Stefan murdering his own father and disposing of the body in various ways. Burial, for instance, warranted a different ending than dismemberment. Another ending had Stefan magically shunting his consciousness back into his 5-year-old self when his mother was still alive.

One’s overall impression of the film, of course, would largely be dictated by the ending they saw first. If the ending was bad, then “Bandersnatch” would be an unsuccessful experiment. If the ending was interesting, then “Bandersnatch” would be brilliant. Perhaps ironically, Brooker feels that one of the film’s more inspired endings wasn’t exactly what he wanted. He said as much in a 2019 interview with the Independent.

The metaphysical ending

The ending in question involved Stefan “chatting” on a 1984-era computer with a mysterious artificial intelligence of some kind. He is baffled by the voice on the other end of the computer. The viewer gets to decide what information Stefan is allowed to have. Is he a computer programmer … or is he a fictional character in a movie? A viewer would be allowed to reveal to Stefan that he is in a Netflix special, having to explain to him what Netflix is and how modern TV works. The camera will pull back, the characters revert to being the actors they are in real life, and the artificiality of the experiment will be laid bare. This is notably clever as a viewer will likely be unable to stop thinking about the experimental nature of “Bandersnatch” while watching. With the metaphysical ending, the artificiality of the thing is lampshaded.

Brooker didn’t like that lampshading, feeling that viewers who saw that ending first were getting the wrong message from his experiment. While the ending was going to be dictated by the viewer, Brooker hoped that the meta ending would be saved for later. Sadly, he couldn’t control that. He said:

“We always knew it was experimental. You’re relinquishing a lot of control and you don’t know which ending the viewer is going to get to first. Are there endings I would change? Probably. For instance, there’s one part which is quite meta, fourth-wall breaking, when you tell Stefan he’s a character on Netflix. Originally, that was held back. But we thought it was so different, so we opened it up early on. What that meant was that some people went down the meta path first and that colors their experience.”

The other Netflix experiments

As someone who did see the meta ending of “Bandersnatch” before seeing any others, I can say that it is the smartest ending. The branching, video-game-like narrative experiment makes more sense if the very nature of its medium is addressed directly. Brooker may have felt it was a little too Marshall McLuhan, but this viewer enjoyed it. The other endings would place “Bandersnatch” in the realm of other more typical thrillers. It’s shocking and well-assembled, but a mere thriller nonetheless.

“Bandersnatch” was not the last time Netflix would try the branching narrative movies, having since produced numerous other such TV specials and movies. There was an irreverent Tex Avery-style cartoon called “Cat Burglar” which was a slapstick museum heist movie wherein the viewer dictated the choices of the cat protagonist. The success of the character depended on one’s speed and accuracy in miniature trivia questions. There was an interactive spin-off of “The Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt,” called “Kimmy vs. The Reverend,” a few survival-based nature documentaries, as well as animated specials connected to “Carmen Sandiego,” “Captain Underpants,” “Puss in Boots,” “Stretch Armstrong,” “The Boss Baby” and “Johnny Test.” If one has a whole afternoon to blow with the kids, then one will find a rather elaborate film in “Minecraft: Story Mode.”

Interactive feature films have always led to a few interesting discussions as to the division between cinema and video games, and whether or not interactivity bolsters or is anathema to art. Regardless of how one feels, these kinds of experiments are always going to result in fascinating views of the two respective media and speculations as to a future where they may find themselves increasingly chummy.

[ad_2]

Source link