[ad_1]

The discounts on cars and trucks that US dealerships traditionally offer over holiday weekends have vanished as tight supply has turbocharged pricing enough to help fuel inflation.

Eric Frehsee, president of family-owned Tamaroff Jeffrey Automotive Group in suburban Detroit, remembers how as a teenager, Labor Day at the dealership meant balloons, barbecue and discounts designed to clear the lot before the next year’s models began arriving in October.

But the business of selling cars has changed so much since the pandemic’s start that Frehsee, now 37, is closing the dealership for the weekend. If a customer wants to buy, the finance manager is watching his iPad.

“We’d always have a three-day blitz, with additional incentives and rebates and special financing,” he said. But now, as manufacturers struggle to produce enough vehicles to feed consumer demand, “incentives have kind of gone away, so there’s no need for that blitz”.

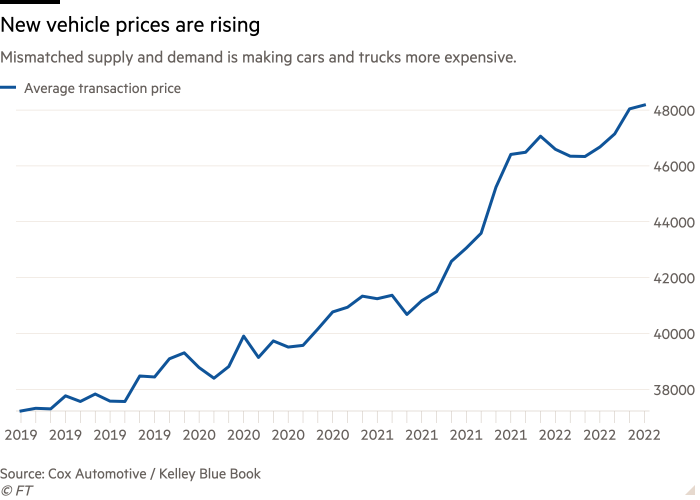

The price of a new vehicle has climbed steadily over the past two and a half years. The average transaction price reached a record-setting $48,182 in July, an increase of 24 per cent since March 2020, according to data from Kelley Blue Book, a brand owned by Cox Automotive.

New and used vehicle prices have helped to drive inflation upward over the past year. The consumer price index in July rose 8.5 per cent over the previous 12 months. The price for new vehicles rose 10.4 per cent in July, while used cars and trucks climbed 6.6 per cent. Together the two categories contributed 0.7 percentage points to the overall increase.

Price growth has been fuelled by what EY-Parthenon chief economist Gregory Daco called a “significant mismatch” between vehicle supply and demand.

Consumer demand for new cars and trucks rebounded more quickly than carmakers expected after Covid-19 forced plants to suspend production for months. The supply of new vehicles tightened further last year when carmakers worldwide confronted a shortage of semiconductors, a key component in systems ranging from power steering to anti-lock brakes.

Inventories at dealerships around the US sit at near-record lows. In July, dealers reported they had between 30 and 40 days of inventory on hand, according to Kelley Blue Book. Inventory has increased 27 per cent from a year earlier, when days’ supply dipped into the 20s.

At Frehsee’s business, inventory has dipped from a 120-day supply three years ago, to 10. His lots used to have about 1,000 vehicles parked on them. Now it is fewer than 100, and cars and trucks are parked horizontally to make the lots appear fuller. Half the 200 vehicles he has arriving this month are already sold.

While the current level of about 1.1mn new vehicles for sale is too lean for the industry, it is unlikely to ever rebound to pre-pandemic levels, when it was more than three times higher, said executive analyst Michelle Krebs at Cox Automotive.

“Automakers and dealers have learned that demand outstripping supply means bigger profit margins and less discounting,” she said.

Incentives in August decreased 51 per cent compared to a year ago, to an average of $877 per vehicle, Deutsche Bank analyst Emmanuel Rosner wrote in a note.

Tamaroff Jeffrey is selling most cars and trucks these days at the manufacturer’s suggested retail price, Frehsee said. The dealership has had record profits. But he worries that sales could decline if changing economic conditions make the vehicles less affordable. For now, many of his customers are trading-in leased vehicles with substantial equity, and those trade-in values work to keep their new vehicle payments in the range they are used to paying.

“Rising gas prices, rising interest rates and the decrease of incentives are leading to much higher car payments, and with the economy being so volatile right now there are definitely concerns about people . . . being able to absorb all these increases,” he said.

The median period a US consumer owns a vehicle is six years. JD Power analyst Tyson Jominy said that means there are still Americans who have not shopped for a car or truck since before the pandemic “and are completely unaware of the conditions at a dealership: All you basically see are asphalt or used cars.”

But even if a recession looms on the horizon, he said, low inventory levels, high pricing and limited discounts mean the industry will be well prepared. The large, eye-catching props that car dealers have traditionally used to capture consumers attention will not be necessary.

“Do not expect any great deals, do not expect the inflatable gorilla to be out there,” Jominy said. “It’s not the same sales environment this Labor Day.”

[ad_2]

Source link