[ad_1]

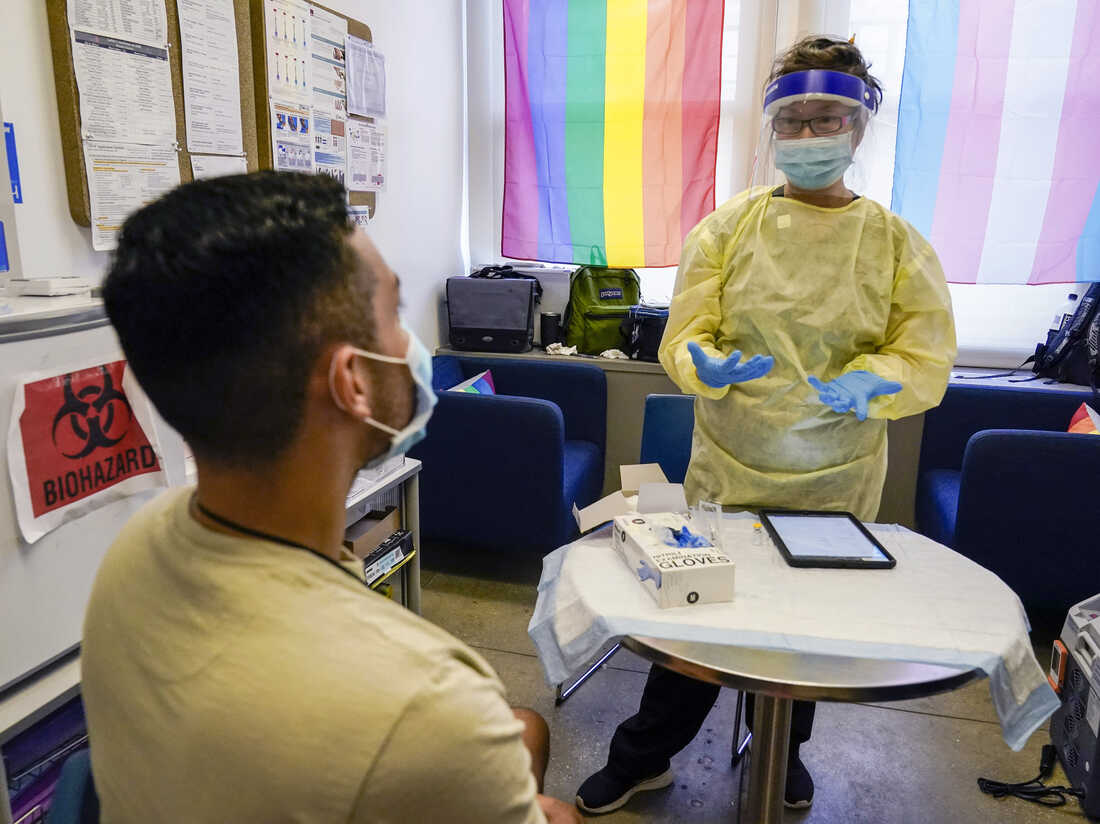

Physician Assistant Susan Eng-Na, right, administers a monkeypox vaccine during a vaccination clinic in New York. New cases are starting to decline in New York and some other U.S. cities.

Mary Altaffer/AP

hide caption

toggle caption

Mary Altaffer/AP

Physician Assistant Susan Eng-Na, right, administers a monkeypox vaccine during a vaccination clinic in New York. New cases are starting to decline in New York and some other U.S. cities.

Mary Altaffer/AP

More than three months into the U.S. monkeypox outbreak, there’s a new – and welcome – phrase coming from the lips of health officials who are steering the country’s response: cautious optimism.

The change in tone reflects early signs that rates of new infections are slowing in some of the major cities where the virus arrived early and spread quickly, in particular New York City, Chicago, and San Francisco.

Federal officials warn it’s still too soon to make pronouncements about the country turning a corner. Still the slowdown in some parts of the U.S. – coupled with data about how those at highest risk are protecting themselves and getting vaccinated – are promising signs.

“Our numbers are still increasing, [but] the rate of rise is lower,” Dr. Rochelle Walensky, director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, told reporters on Friday. “We’re really hopeful that many of our harm reduction messages and our vaccines are getting out there and working.”

Reported case numbers have been trending down since mid August, based on an NPR analysis of data the CDC released Wednesday. Overall, there’s been around a 25% drop in the 7-day average of new cases over the past two weeks.

However, health officials caution that lags in data reporting can offer an incomplete picture of the outbreak in recent weeks, making it hard to know if cases have truly peaked.

The decline in parts of the U.S. mirrors what’s already being seen in some European countries, where the virus was detected a few weeks earlier. In both the U.K. and Germany, daily case counts have steadily dropped since late July. In several other countries, including the Netherlands and Italy, the number of new cases have plateaued.

Cases slow down in big cities

In New York City – one of the epicenters of the outbreak – the number of new people being infected has dropped 40% over the past month. San Francisco health officials are also seeing a decline in the rate of new cases.

“I’m cautiously optimistic,” says Dr. Susan Philip, health officer for the city and county of San Francisco. “We know, though, it’s going to take a lot of work and effort to sustain that downward curve and to make sure that cases continue to go down.”

The picture is also improving in other cities like Los Angeles, Houston and Chicago where local health leaders say there are indications that infections are leveling off.

Key metrics – such as the average number of cases and the time it takes for cases to double – have decreased over the past couple of weeks, says Janna Kerins, medical director at the Chicago Department of Public Health. “I’m not sure we’re ready to say this outbreak is truly ending,” Kerins says, “But all of those things are encouraging.”

The changes also track with modeling released this week that suggests the national outbreak is on the decline.

“We are seeing signs of a substantial slowdown and the forecasts suggest that this is going to go in the right direction,” at least over the next four weeks, says Gerardo Chowell-Puente, professor of epidemiology and biostatistics at the Georgia State University, who’s modeling the monkeypox outbreak

Changes in behavior drive the decline

Given the size and diversity of the U.S., there’s still considerable uncertainty on how the outbreak will play out in different parts of the country, but infectious disease experts largely attribute the slowdown to efforts to change behavior among gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men – a group that accounts for the vast majority of cases.

“Most of us in public health who work on this disease are quite confident that the majority of the reduction is due to change in behavior,” says Dr. Jay Varma, director of the Cornell Center for Pandemic Prevention and Response at Weill Cornell Medicine.

More than 94% of monkeypox cases in the U.S. are associated with sexual activity. And on Friday, CDC officials highlighted new data showing that gay and queer communities are modifying their sexual behaviors in response to messaging around monkeypox.

In one online survey, about 50% of respondents said they had reduced “their number of sexual partners, one-time sexual encounters [or] use of dating apps because of the monkeypox outbreak.” An accompanying modeling study released by the CDC showed that a “40% reduction in one-time sexual partnership might delay the spread of monkeypox and reduce the percentage of people infected” by up to about 30%.

“What this means is that the LGBTQIA+ people are doing things that are actually reducing their risk, and it’s working,” said Dr. Demetre Daskalakis, White House monkeypox response deputy coordinator, at a press briefing Friday.

It’s not entirely surprising that the virus appears to be slowing down in the U.S. as it has in Europe, says Dr. Jeffrey Klausner, a professor of medicine and infectious diseases, population and public health sciences at the Keck School of Medicine at the University of Southern California.

“Most of the cities will see a decline in cases – that decline may not be as fast or as steep as the ascent,” says Klausner.

Klausner notes that monkeypox has stayed mostly within certain relatively small sexual networks – that makes it harder for the virus to maintain momentum as vaccination increases, people build up immunity from infection and those at highest risk change their behavior.

“People who raised concerns about the spread of infection on college campuses and daycares and other kinds of settings where there’s close personal contact, at this point, that hasn’t occurred,” he says.

Uncertainty remains

But other experts are not as sanguine about the trajectory of the outbreak – at least not yet.

“It’s great to see some declines,” says Anne Rimoin, an epidemiologist at UCLA who has studied monkeypox for years. “But if the downward trend is due to changes in behavior and vaccinations, it’s not clear how long behavioral changes can be sustained, and how well the vaccinations actually work to prevent infections.”

Health officials are urging members of affected communities to keep taking precautions to slow the spread of monkeypox.

“Let me be clear,” Daskalakis said Friday. “The advice about how to reduce risk for monkeypox exposure is for now, not forever, and is an important part of our public health and community response as we urgently surge vaccinations to control this outbreak.”

Still, there isn’t robust real world data on how well the monkeypox vaccine – approved by the Food and Drug Administration in 2019 – protects against infection and transmission. Further complicating the picture is that a shortage of vaccine has led the Biden administration to pursue a new strategy of offering the shots intradermally in order to stretch the supply.

“The laboratory data that we have on the vaccine suggests that it’s going to be very effective in humans,” says Varma. “But what we know in medicine is that until we see what happens in the real world, we never know for sure.”

NPR’s Michaeleen Doucleff contributed to this report.

[ad_2]

Source link