[ad_1]

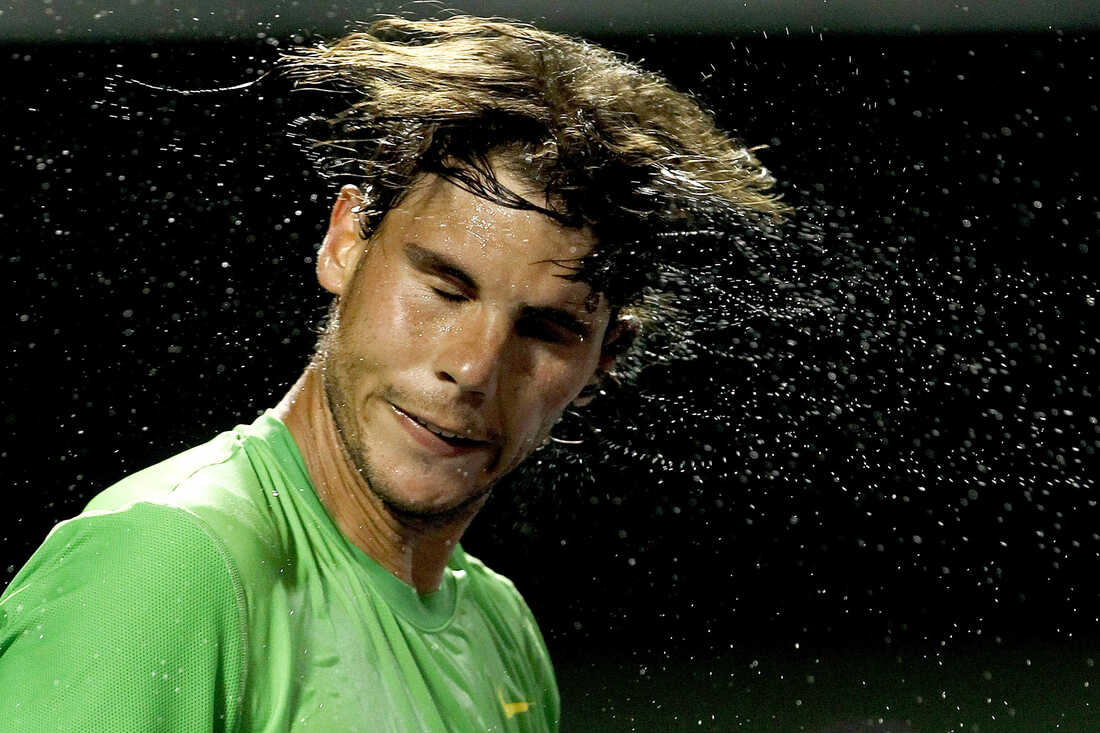

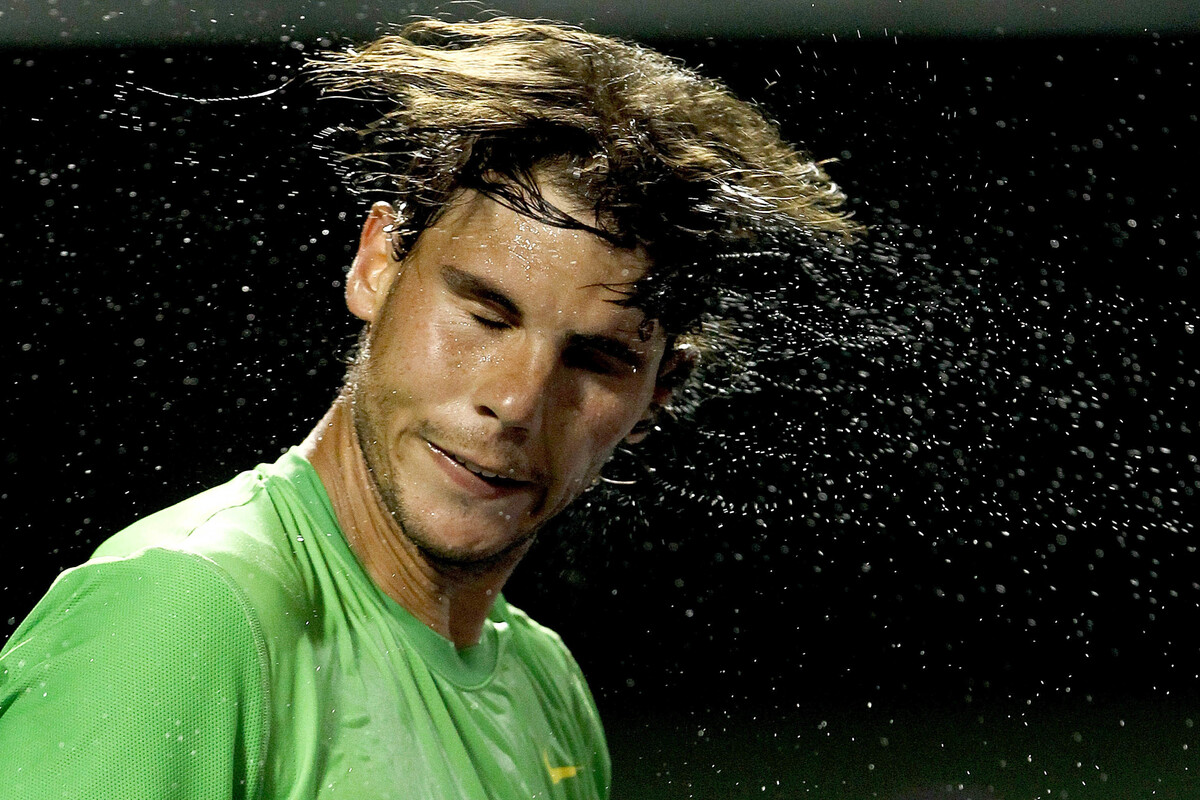

Tennis great Rafael Nadal of Spain might think twice about shaking off his beads of perspiration. It turns out that sweat leads to a surprising health benefit.

Matthew Stockman/Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

Matthew Stockman/Getty Images

Tennis great Rafael Nadal of Spain might think twice about shaking off his beads of perspiration. It turns out that sweat leads to a surprising health benefit.

Matthew Stockman/Getty Images

Back in college, I had an embarrassing moment that’s forever etched into my memory. A girlfriend borrowed my backpack for a weekend trip. And when she came back, she handed me the backpack and said something I’ll never forget:

“Michaeleen, you must sweat a lot because your backpack stinks. The armstraps smell like onions. Ew.”

I stood there in silence, feeling totally ashamed. I’m not sure how I responded. But I remember thinking to myself, “I don’t eat many onions. Does my sweat really smell that bad?”

Now 25 years later, I’ve come to find out that my stinky sweat was actually a signal of something good on my skin – something that prevents skin problems, like eczema, and protects me from dangerous infections such as MRSA,, which is found in hospitals around the world and is the leading cause of skin infections in the U.S.

What creates your body’s unique bouquet?

To figure out what I’m talking about, we need to step back and look at what actually creates body odor. It’s not the sweat itself.

“No, I don’t think your sweat by itself smells,” says microbiologist Gavin Thomas at York University. “It certainly doesn’t have these really stinky, odorous molecules.”

Thomas studies how – and why– humans have a particular bouquet of scents. He says that sweat, immediately after it comes out of your pores, is essentially odorless.

“So most sweat is salty water,” he says. That’s the sweat that’s secreted pretty much all over your body and cools you down when you’re hot.

“But that’s not what we’re interested in,” he explains. “We’re interested in this other type of sweat, which is produced in our underarms and around the genitals.”

This other type of sweat isn’t just salty water but also contains a cornucopia of compounds, including oils, fats and proteins.

No one knows exactly why humans have this second type of sweat. But, Thomas says, one purpose likely has to do with the odors that it ends up emitting.

On its own, this second type of sweat isn’t smelly. But something living on our skin – tiny creatures – takes that sweat and makes it stinky.

Yes, I’m talking about the bacteria on your skin.

Warning: This illustration “grossed out” our visuals editor! It depicts bacteria around a sweat gland pore on the surface of human skin. Sweat pores bring sweat from a sweat gland to the skin’s surface. Some of these bacteria enjoy eating the molecules in our sweat. Then they spit out new molecular compounds, some of which can be quite stinky.

Juan Gaertner/Science Source

hide caption

toggle caption

“The human skin has almost 200 different species of bacteria living on it,” says biologist Teruaki Nakatsuji at the University of California, San Diego. “And each person has different strains of these bacteria. So the skin microbiota is so diverse.”

These bacteria are hungry. And some of them really enjoy eating the molecules in our sweat. They munch off a piece of the molecule and then spit out new molecular compounds, some of which are quite aromatic. For example, they can smell like cumin or goats, the American Society for Microbiology asserts.

And some of these molecules are downright stinky.

Back in 2020, Thomas and his colleagues found that one critter on the skin, called Staphylococcus hominis, produces an especially pungent odor: “We’ve had people describe it as kind of an onion smell or a cheesy onion smell,” he says. “These types of compounds do smell pretty bad.”

But wait! This critter – and your stinky sweat – is actually beneficial and even necessary.

So back in college, when my backpack smelled a bit stinky, it wasn’t so much my sweat to blame but rather a little microbe called Staphylococcus hominins.

Which may make you want to go take shower stat. But wait! Before you go grab the antibacterial soap, there’s something about this bacteria you need to know. Something that I didn’t realize until recently: These bacteria – and their relatives – actually do something really good for you and your skin. In fact, you need these bacteria.

“Without S. hominins, you’re in trouble,” says dermatologist Richard Gallo at the University of California, San Diego.

Over the past five years, Gallo, Teruaki Nakatsuji and their colleagues have published a series of studies showing how S. hominins actually protects our skin from inflammatory problems, such as eczema, and dangerous infections, including Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, or MRSA.

The team has even developed a cream, made with the bacteria and tested in preliminary trials, as a treatment for eczema.

“S. hominins basically make a type of antibiotic, which specifically targets the bacteria that causes MRSA,” Gallo says. “And it kills this bacteria by punching holes in its cell membrane.”

But, Gallo says, this critter isn’t the only part of your skin that produces antimicrobial agents. Twenty years ago, he and his colleagues found that your body itself also makes antimicrobial molecules and puts them inside your sweat.

“So sweat is almost like an antibiotic juice,” Gallo says. “And as the water evaporates, those antibiotics actually increase in concentration. So it kind of leaves a little coating on your skin. So that’s one of the ways our skin tries to fight the bad bacteria.”

So the next time you’re hot, sticky and maybe a bit stinky, before you hit the shower, take a moment to thank your sweat – and the bacteria that eat it – for helping to keep your skin healthy and safe.

Because even after you do take a shower, the protective critters will still be there to help you, Gallo says — even if you use antibacterial soap.

“When you wash your skin, you get rid of the material on its surface,” he says. But these bacteria live deep inside your skin’s pores, where detergents and antibiotics can’t reach. “So within 10 minutes after washing, the bacteria grow back and populate your skin’s surface.

“So in a way, your skin is smarter than you,” he adds. It knows what it needs better than you do.

[ad_2]

Source link