[ad_1]

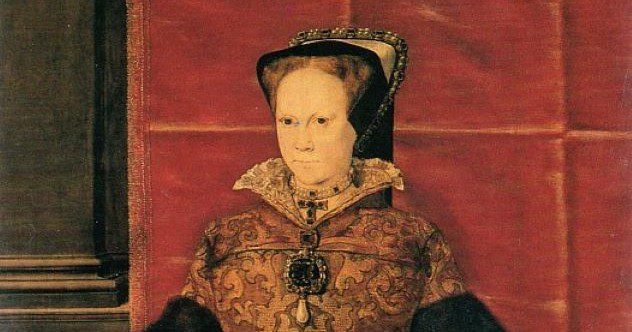

Mary I of England was the only surviving child of King Henry VIII and his first wife, Catherine. As the Catholic queen of a country that had fallen into religious conflict and established a breakaway church, she saw it as her duty to bring her subjects back under the “true” religion. This led her to persecute hundreds of Protestants after she came to power.

Overshadowed by her sister and successor, the Protestant Elizabeth I, Mary has largely been pushed aside in the public’s imagination. Today, most people associate her reign only with the Marian persecutions, and her chilling moniker, “Bloody Mary,” is probably more famous than she is. But as with most historical figures, there’s more to her story.

Here are ten reasons Mary wasn’t as evil as we’ve been taught.

Related: 10 Intriguing Spies From The Tudor Era

10 Born into a Divided Family

Mary’s mother was Catherine of Aragon, a Spanish princess who’d been betrothed from a young age to Prince Albert of the House of Tudor, then heir to the English throne. Shortly after the marriage, Albert, in typical medieval fashion, succumbed to an untimely death, leaving the teenaged Catherine a widow in a foreign land. Albert’s father, Henry VII, was also widowed and considered marrying Catherine himself but eventually proposed she wed his younger son and new heir, the future Henry VIII.

Negotiations over the marriage took so long that by the time it happened, Henry had already succeeded his father, and Catherine was in her twenties. It was into this tangled mess that Mary arrived in 1516 after several failed pregnancies. Her birth came at a time when royal parents were not exactly on the up and up regarding daughters being equal to sons. Altogether, Catherine gave birth to six children, including three sons, but none survived except Mary. The absence of a male heir eventually completely pulled Henry VIII away from his family.[1]

9 Traumatized as a Teenager by Her Father

With no male heir, Henry VIII grew increasingly obsessed with the topic, seeking desperately to find an explanation for his lack of sons. Renaissance enlightenment principles aside, he concluded that by taking his brother’s widow as his wife, he’d broken the laws of God and been cursed with no heirs, even though the marriage had been sanctioned by the Vatican. Whether he legitimately believed this or simply found it a convenient pretext to remarry, only he knew.

Although Mary was already being educated as heiress presumptive, Henry remained vehemently opposed to a female successor. First, he appealed to the Pope to dissolve his marriage to Catherine. When that failed, he enlisted allies to continue with annulment proceedings domestically, undertook a secret marriage to his mistress, Anne Boleyn, and appointed himself Supreme Head of the Church in England. To uphold the claim that his marriage to Catherine had never been valid to begin with, he delegitimized the teenage Mary and removed her from the line of succession, all before Anne’s first child had even been born.[2]

8 Humiliated and Forced to Wait on Her Baby Sister

In 1533, Anne gave birth to Elizabeth, her first and only child with Henry. Having been stripped of her royal titles, Mary was further humiliated by being made an attendant to her infant sister, who had replaced her in the line of succession. To make matters worse, Mary’s mother, Catherine, by this point, had been banished from court, and mother and daughter were officially forbidden from communicating.

For years, Mary refused to cave to pressure to accept her illegitimacy and recognize her father as head of the church, a testament to her strength of character in the face of what must have seemed insurmountable odds. Eventually, she did make those pronouncements but sent a secret message to the Pope explaining she’d done so under duress. Despite what Elizabeth’s birth and position represented for her, Mary loved her sister and was influential in getting her back on good terms with their father after he executed Elizabeth’s mother, Anne, for treason.[3]

7 Spared the Life of Her Usurper

After Henry VIII’s third wife, Jane Seymour, gave birth to a son named Edward, Mary assumed she’d never be queen. If all went according to Henry’s plan, Edward would succeed him and have sons of his own. And Mary would live the life of any ordinary princess. Edward did become king but lived only a few years after that, dying in his teens of a respiratory illness, having neither married nor had children. Although their father had reinstated Mary to the line of succession, Edward again removed her as he lay dying, not because he didn’t want a female heir but because he didn’t want her to undo the work of the Reformation, in which he’d been brought up.

Edward and Mary’s sister Elizabeth had also been raised Protestant, like Edward, but legally it would’ve been inadvisable to exclude only Mary, who held the stronger claim as the eldest. To this end, he also bypassed Elizabeth and instead designated his Protestant cousin, Jane Grey, as heir. After Edward’s death, Jane’s reign lasted a matter of days, with Mary rallying supporters and marching on London. Knowing Jane had only followed orders, Mary spared her life. Tragically, Jane remained a pawn in the conspirators’ dealings and eventually was put to death to thwart further attempts to unseat Mary.[4]

6 Courageous and Trailblazing for the Time

Although feminism wasn’t exactly a hot topic in Mary’s time, her life was as close an example to it as we might expect for a sixteenth-century queen. In one of her most daring moments, Mary fled to a loyalist outpost as soon as she heard that her brother, Edward VI, was near death. If she’d remained nearby, she’d have been imprisoned and prevented from ascending the throne by Edward’s supporters, spelling the end of the Tudor dynasty. She was bold, decisive, and politically astute in an era when women were chiefly praised for modesty and obedience.

As Henry VIII’s eldest surviving heir, Mary based her claim to the throne on legitimacy, sidelining the topic of religion. This gained her support from both Catholics and Protestants. Both the common people and gentry came to her side, and Jane Grey’s government fell apart within days. Not long after Mary’s proclamation, Parliament passed an act enshrining the full and absolute power of the crown irrespective of gender, establishing equal rights between kings and queens regnant.[5]

5 Guided by the Religious Conventions of Her Time

Today, we’d be horrified at the idea of burning someone at the stake for any reason, let alone their religious beliefs. But Mary grew up in a time when the importance of practicing the true religion was a matter of salvation. She believed her brother’s death proved God wanted a Catholic on the throne. Seeing the Pope as God’s representative on earth, she rejected the title of Supreme Head of the Church.

For Mary, finding herself on a throne she thought she’d never ascend was a vindication of her beliefs. To allow England to continue its course of separation from the Vatican would’ve been an affront to her duties as sovereign. Protestants who refused to convert back to Catholicism paid with their lives in a gruesome manner, but everything Mary had been taught told her it was her obligation to root out heresy in her dominions.[6]

4 No Different from Other Monarchs of the Age

Giving someone the title “Bloody Mary” conjures up images of a cold, ruthless killer. And though you might argue the shoe fits, the truth is Mary was no different from other monarchs of the time when it came to eliminating disobedient subjects. In pursuit of his ambition to leave his marriage and father sons with other women, Henry VIII, who never quite reconciled his Catholic upbringing with his zeal for reform, put both Catholics and reformers to death, including death by burning.

Mary’s successor, Elizabeth I, not only executed many of her own subjects but even put to death a fellow queen. While it’s true that Mary’s infamous burnings reached almost 300 in a short period, Elizabeth once ordered over twice as many executions after quashing a Catholic rebellion early on in her rule. Of course, neither sister ever reached the dizzying heights of their father. By the end of his 36-year reign, Henry VIII had executed an estimated 57,000 people, a bone-chilling average of 1,500 death sentences a year. Among the victims were two of his own wives. And these numbers leave out what was happening in other parts of the world whose leaders were often even more brutal.[7]

3 Counter-Reformation Was Popular During Her Reign

Since it was ultimately unsuccessful, it’s easy to imagine Mary’s attempt to re-Catholicize England as unpopular, but the truth is it wasn’t. Of course, those who subscribed to the principles of the Reformation were opposed, but Mary came to the throne less than a quarter-century after her father’s break with Rome. At that time, the question of religion in England was far from resolved, with Catholics still outnumbering Protestants.

Before Mary even set out her religious policy, news of her accession brought the revival of Catholic Mass in churches across the realm. She was no tyrant either—Parliament largely supported Mary’s policies and repealed most of her brother’s and father’s reforms. Eighteen months into her reign, England was fully realigned with the Catholic Church. Had Mary produced an heir, the child would’ve been raised Catholic, the Reformation may have fizzled out, and the restoration would’ve gone down in history as a cornerstone of her reign.[8]

2 Laid the Groundwork for Some of Her Successor’s Achievements

Mary’s reign has largely been characterized by historians as ineffective and backward-looking, but these are oversimplifications. The two biggest “failures” of Mary’s reign—attempting to re-Catholicize England and the loss of the historically English territory of Calais in France—are often judged out of context (as we’ve already seen concerning the restoration). Future English monarchs presided over the loss of territories much more extensive than Calais, but it didn’t define their reigns, nor was it seen as evidence of their unsuitability.

In fact, Mary was a conscientious monarch who worked tremendously hard. Although her marriage to a foreigner was initially unpopular, she ensured her rights as queen were not ceded to her husband. During her reign, she undertook reforms in the navy as well as in coinage and the militia, reendowed several hospitals, and established a groundbreaking trading company with Russia. A revised customs book increased crown revenue and remained in effect through the reign of her successor. She also had plans drawn up for currency reform, which were carried out after her death.[9]

1 Died Too Soon to Consolidate Her Policies

Despite having suffered from ailments of the reproductive system for years, Mary was eager to birth an heir and secure the succession. In 1554, she married the future Philip II of Spain, but the union produced no children. Although Mary was genuinely in love with her husband, by the time it was apparent she wouldn’t become pregnant, he’d retreated to his own dominions abroad. His absence affected her greatly, perhaps eliciting bitter memories of abandonment from her youth.

Only five years into her reign, Mary died during a flu epidemic at 42, having spent the last months of her life suffering from the same chronic disorders that had plagued her since adolescence. With no heir of her own, she had no one to carry on her legacy, and her reign proved much too short for her policies to take effect. Although considered illegitimate by Catholics, her sister Elizabeth was crowned in 1559 and soon reestablished the Protestant church. Her reign has largely gone down in history as a golden age, in sharp contrast with Mary’s.

It’s often said that history is written by the victors. Mary I of England, whose motto as queen was “Truth, the daughter of time,” would probably agree.[10]

[ad_2]

Source link