[ad_1]

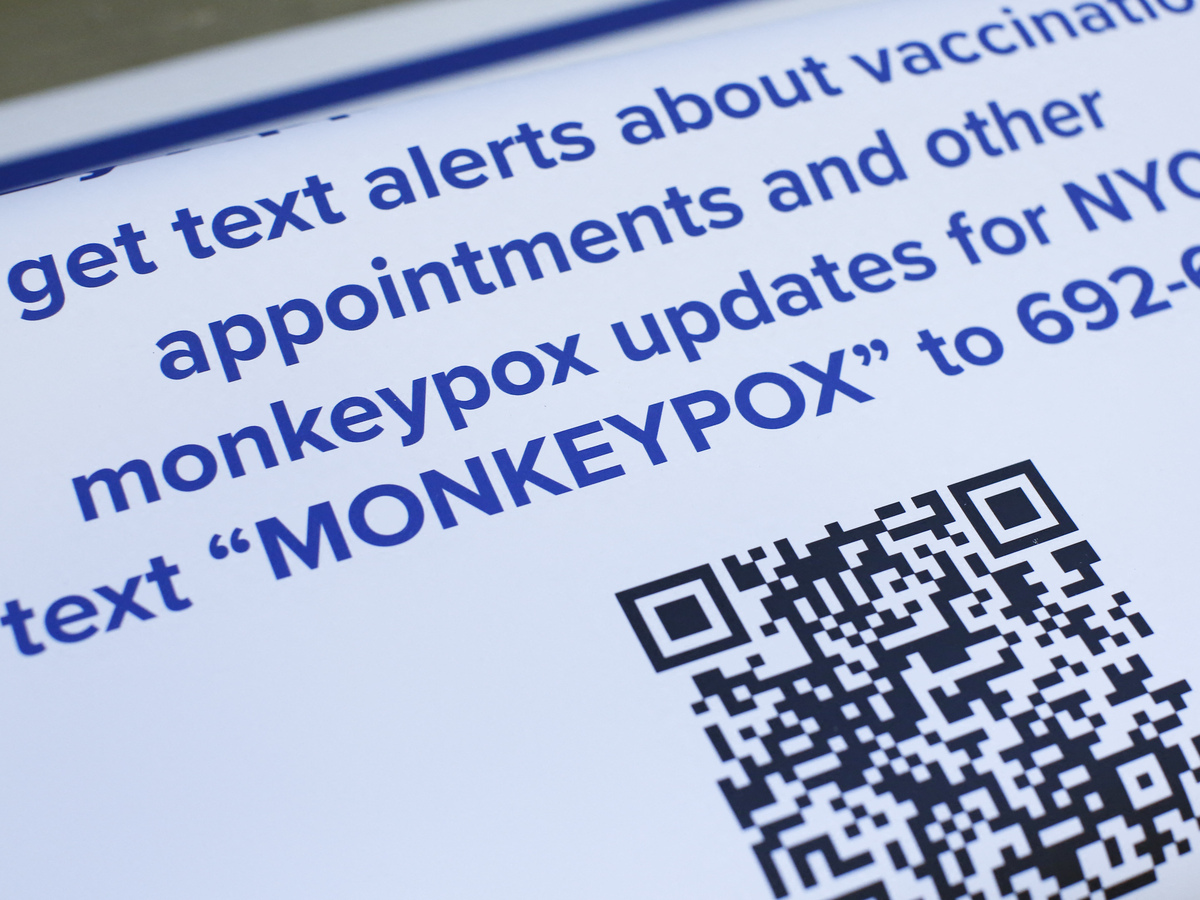

Informational posters are displayed at a monkeypox mass vaccination site at the Bushwick Educational Campus in Brooklyn on July 17.

Kena Betancur/AFP via Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

Kena Betancur/AFP via Getty Images

Informational posters are displayed at a monkeypox mass vaccination site at the Bushwick Educational Campus in Brooklyn on July 17.

Kena Betancur/AFP via Getty Images

As places like San Francisco and New York state declare the monkeypox outbreak a public health emergency, there’s a major question: how to talk about the virus in the first place.

Monkeypox, also known as hMPXV, has been spreading across the U.S. since May. As of Friday, there have been over 5,100 confirmed cases in the U.S., according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The virus causes similar symptoms to smallpox, like a rash, fever and headache. It’s transmitted through close physical contact and it’s rarely fatal.

Although anyone can get infected, the outbreak appears to have largely affected men who have sex with other men. That’s led some public health officials to question how to raise awareness about the spread without making the early public health mistakes of the HIV/AIDS crisis when gay and bisexual men were stigmatized and discriminated against.

It’s a tricky conversation but it matters, said Dr. Joseph Lee, a professor of health education and promotion at East Carolina University who has studied public health messaging.

“We need to make sure we’re getting the right people involved in reaching the right communities and saying things in a way that resonates,” Lee told NPR. “Because the harm of getting it wrong is real and hard to repair.”

Be honest but avoid overemphasizing one group’s risk over another, experts say

Fixating on how the virus impacts different populations can be unproductive and unhelpful, Lee says.

On one end, it tends to make people who are disproportionately impacted feel fatalistic and less likely to seek help, he added. On the other end, it makes those who have been less impacted inaccurately believe they are less vulnerable.

“You can recognize that there are differences and that’s important to do, but it doesn’t mean it has to be the emphasis or message of the campaign. It just tells you who the messaging needs to go to,” Lee said.

Overemphasis can also lead to assumptions about why the disparity exists and activate harmful stereotypes.

With that, don’t overemphasize sex either

Monkeypox isn’t a sexually transmitted disease and sex is only one way that the virus can spread. Still, local public health officials have debated whether to advise gay and bisexual men in particular to abstain from sex during the current outbreak.

Joaquín Carcaño, the director of community organizing at the Latino Commission on AIDS, said that guidance is not only ineffective but can pose more risk.

“We know abstinence-only education doesn’t work for pregnancy, so why would we use it for this?” he told NPR. “When you say no sex, you’re mischaracterizing that MPV, also known as monkeypox, is a sex-associated transmission, which it can be, but it’s not the end all be all.”

Carcaño, who has been working to debunk misinformation around the virus, also worries that overstressing sex can likely make people dismiss public health guidance altogether. Instead, he recommends phrasing like, “limit physical encounters” and “limit intimate, long-session, encounters.”

Tailor your messaging for different audiences

The broader the messaging, the less likely it will resonate with all audiences, said Dr. Tyler TerMeer, the chief executive officer of the San Francisco AIDS Foundation.

“It is really important to know who your audience is and to create a set of messaging that will be relatable and that’s going to resonate,” TerMeer said.

The foundation published an online health guide in advance of this weekend’s Up Your Alley festival, which is a leather and fetish street fair. The leaflet offers specific advice on how to safely participate in the event, including whether to wear latex, attend bondage performances and social distance at parties.

TerMeer added that it was important to make sure the pamphlet was approachable, sex-positive and realistic to people’s responses while still based in facts. He plans to continue to create tailored messaging for events in the future if needed.

Remind people that there are proactive steps to take

Experts caution against fear-based messaging, especially when it targets communities that have historically been discriminated against.

Although it’s important to stress the seriousness of the virus, it’s equally crucial to underscore that testing and vaccines exist. In that vein, the outbreak is a lot more preventable and manageable than the HIV/AIDS crisis back in the 1980s.

TerMeer told NPR he hopes that once public health officials grapple with how to effectively talk about the virus, they can focus on even more urgent issues like reducing the bureaucratic barriers to access to testing and treatment.

“The fact that we are continuing to have to ring the alarm to get the resources we need is unacceptable,” he said. “It does make many of us wonder if it would have had any more urgency if it wasn’t impacting a community that has for so long been marginalized.”

[ad_2]

Source link