[ad_1]

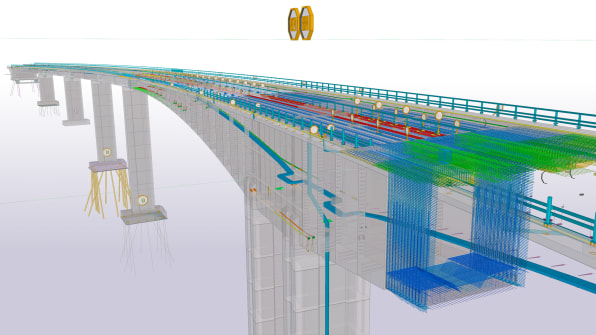

Soaring above a forest outside of Oslo, Randselva Bridge is remarkably unremarkable. A straightforward viaduct for cars and trucks, the gently curving bridge straddles a river, a valley, a rail line and foothills. The bridge stretches 634 meters, or 2,080 feet, and stands 180 feet above the ground at its highest point. Like many highway projects around the world, it has been engineered to span great distances and stand strong—feats that have become so normal they’re expected as the status quo. But unlike most large-scale building projects, this bridge has been designed and constructed without any drawings.

Construction blueprints, the two-dimensional drawings that detail how contractors turn designs into a finished project, were completely eliminated. When it opens to traffic next month near the city of Hønefoss, the bridge will be the longest ever constructed without 2D drawings.

This feat was made possible by a new approach to designing and constructing projects. Using one highly detailed digital three-dimensional model this approach is saving time and money on what can be expensive, slow and complex building projects.

Known as building information modeling, or BIM, this process removes what had become a problem-plagued step in construction. For the past decade or so, with the advancement of digital design software, most big construction projects have been designed digitally as 3D models. Once complete, these models would get turned into large sets of 2D drawings that contractors and suppliers used to plot out the step-by-step construction process. Any issue encountered during construction would require changes made to the digital model and the creation of new construction drawings—changes that are as common as they are expensive.

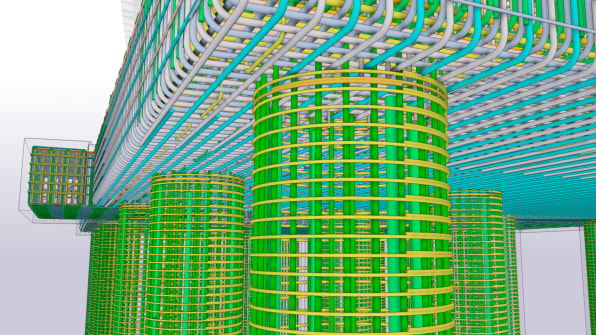

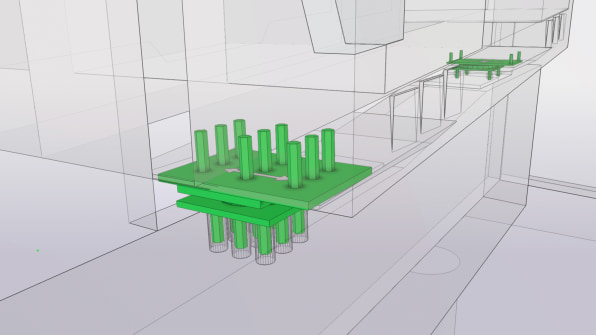

For Randselva Bridge, engineering company Sweco opted for a fully digital approach, using one model of the project that would be used and amended throughout the design and construction process. Using a BIM approach, the project was able to eliminate the need for 2D drawings, and instead allowed the 3D model to be used by the contractors for every step of construction, according to Øystein Ulvestad, a BIM developer for Sweco who led the design of the project.

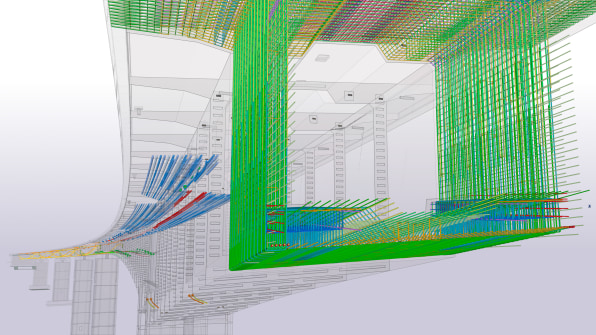

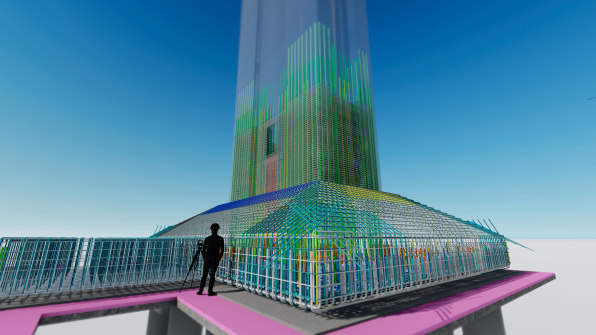

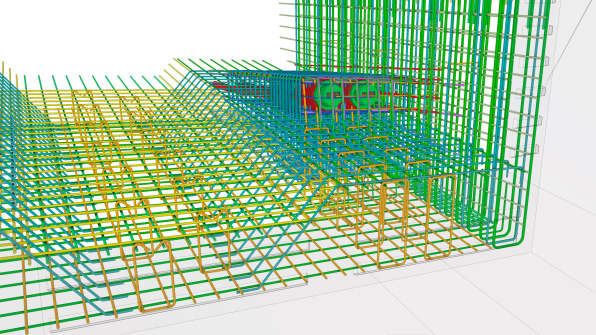

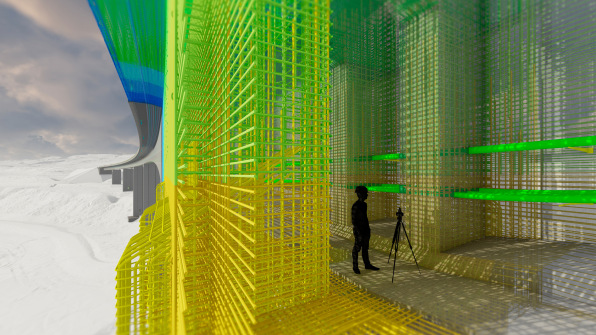

“Every object in the model has data connected to it,” Ulvestad says. As each section is constructed and scanned, any subtle changes to the structure can be immediately reflected in the model, making it easy to adjust future sections still to be built. If a new section needs to be raised or lowered an inch, the model will show precisely how each piece of construction material is resized to accommodate the change. Instead of building to the original specifications, workers on site will know to follow the updated plans, using tablets and augmented reality to see what needs to be built next and where. “We saw that we would save quite a lot of money in less errors being made,” says Ulvestad.

The construction industry is starting to see the wisdom of this approach. About half of all construction companies have reported using BIM modeling, but adoption has been slow as designers and contractors adapt to a more tech-centric approach to building.

On a typical construction project there are plenty of chances for things to go awry. Ulvestad says the bridge has more than 250,000 individual pieces of reinforcing bars, and about 250 long-span steel cables that serve to keep the bridge at the right tension. “When you would traditionally work to build this with drawings, you’d need about 200 of these drawings. And when you would revise every one of those about five or six times, so you would end up with about 1,000 drawings,” he says. Regular 3D scans of the project help keep the model updated, and point out where changes are needed.

Sweco has designed smaller projects using this approach, and Ulvestad says cost savings on those projects have been around 10% compared to conventional construction, mostly they’ve helped reduce expensive changes to drawings during construction and the extra material orders they require. He says the data is still coming in on Randselva Bridge, but he expects the savings to be even greater.

Other cost savings are also possible, he says, because materials can be ordered and stored as needed, enabling contractors to buy only the parts and pieces they need based on any subtle changes to the project as it’s being built, he says. “You always know exactly how much steel, how much reinforcement, and how much concrete you’re going to need,” Ulvestad says. “It makes life at the building site more flexible and easy.”

This approach also makes collaboration much easier. Several different companies across Europe were involved in designing and building Randselva Bridge, and there was a danger that much would be lost in translation for such a big project.

“When you do engineering, every country has its own way of making drawings. On this project, we were teams of engineers sitting in five different countries with five different ways of doing drawings,” Ulvestad says. “Since BIM models are very universal, this kind of cross-country collaboration was a lot easier.”

Ulvestad says eliminating 2D drawings is part of an even bigger transformation coming to the construction industry. Using BIM models, he says many construction projects will soon be able to be built largely through automation. “At the moment it’s people reading these BIM models, but ultimately what we’re doing is preparing for a future where robots will read them,” he says. One day, it won’t just be drawings that are missing from big construction projects. The people will be missing as well.

[ad_2]

Source link