[ad_1]

Did UK inflation stabilise in May?

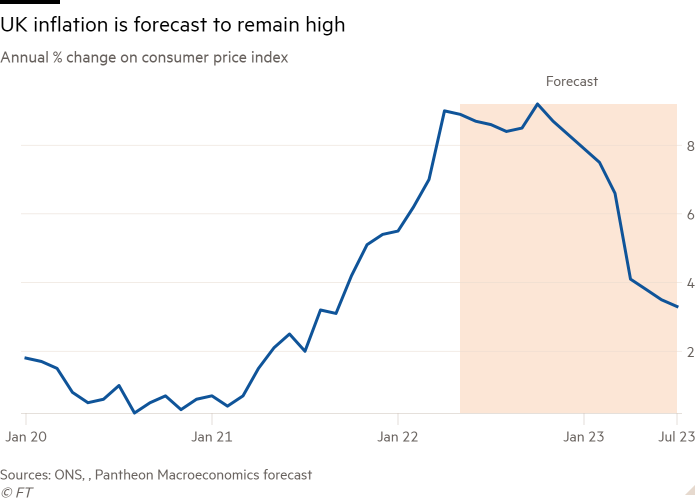

After surging in April, UK inflation is expected to stabilise over the next few months — albeit remaining at historic levels — before reaching new heights later this year.

Economists polled by Reuters expect UK consumer price growth to have hit 9.1 per cent on an annual basis in May. That figure would represent little change from the 40-year high of 9 per cent reached in April, when a jump in the country’s energy price-cap bill led to a sharp rise from 7 per cent in the previous month.

“We are expecting fewer fireworks in the May CPI release,” said Ellie Henderson, economist at Investec. She forecast the headline consumer price index rate to remain at 9 per cent in May, but expects a combination of firmer food costs, higher petrol prices and another steep uptick in the energy price cap in October to push inflation into double figures in the second half of the year.

This is in line with forecasts by the Bank of England which last week said it expects inflation to average above 11 per cent in the last quarter but pointed out that “risks to the inflation projection were judged to be skewed to the upside.”

In order to bring inflation down closer to the bank’s target of 2 per cent, markets expect the bank to increase interest rates to 3 per cent by the end of the year, from the current level of 1.25 per cent. They are also pricing a more-than 50 per cent probability of a 0.5 percentage point interest rate rise at the BoE’s next policy meeting in August, which would be the sixth consecutive rise in rates. Valentina Romei

How far has eurozone inflation hit business activity in June?

As the European Central Bank prepares to end its era of easy money and start raising interest rates, economists will be tracking whether business activity has grown at a slower pace than expected in the face of surging inflation.

A monthly survey released on Thursday is forecast to show that eurozone business activity expanded in June, but at a slower pace than in May. Economists polled by Reuters predict that the ‘flash’ or early reading of the S&P Global composite purchasing managers’ index for the eurozone will come in at 54 compared with 54.8 a month earlier. Any number above 50 indicates growth rather than contraction.

That consensus estimate comes as businesses and consumers in Europe grapple with record inflation levels stemming from supply chain disruption and the soaring price of goods and energy, exacerbated by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

Bert Colijn, a senior economist at ING, said a central factor in determining the health of business activity would be how well the services industry — particularly in southern eurozone economies — has fared after the lifting of pandemic restrictions.

“Also important is whether the manufacturing sector continues to hold up despite supply chain problems and falling new orders,” he said, adding: “Energy price growth remains problematic, but we also hear anecdotal evidence of businesses becoming more careful to price through higher input costs to the consumer.” Nikou Asgari

Norway may have been ahead of other big central banks in tightening monetary policy before the current inflation scare. But even after three rate rises since last September, Norges Bank still faces questions about the pace of future increases when it meets on Thursday.

Most economists expect it to raise interest rates by 0.25 percentage points to 1 per cent, and to indicate that it will speed up future rises. Nordea, the Nordic region’s biggest bank, expects four more increases this year after next week, with the subsequent one due in August, a more rapid increase than Norges Bank indicated in March. By the end of 2023, its main policy rate should be 3 per cent, Nordea believes.

Norway, western Europe’s leading petroleum producer and one of the world’s richest countries, is suffering from many of the same issues as other developed nations — from rising inflation and wage pressure to worries about future growth. But it also has the world’s largest sovereign wealth fund, which provides about a quarter of the government’s budget, and sky-high revenues from oil and particularly gas.

Could Norges Bank be tempted to follow the US Federal Reserve with a large rate rise? The Nordea economists do not believe so, arguing that as 94 per cent of households have floating mortgage rates (versus about 10 per cent in the US) Norway’s policy rate is effectively transmitted to individuals, lessening the need for shock rises of 0.5 percentage points or more. Richard Milne

[ad_2]

Source link