[ad_1]

The NPR Student Podcast Challenge middle school winners Wesley Helmer, Kit Atteberry, Harrison McDonald and Blake Turkey at Williams Middle School in Rockwall, Texas.

Cooper Neill for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Cooper Neill for NPR

The NPR Student Podcast Challenge middle school winners Wesley Helmer, Kit Atteberry, Harrison McDonald and Blake Turkey at Williams Middle School in Rockwall, Texas.

Cooper Neill for NPR

The town of Rockwall, Texas, has a few claims to fame: Bonafide Betties Pie Company, where “thick pies save lives”; the mega-sized Lakepointe Church; and Lake Ray Hubbard, which is lovely until the wet, Texas heat makes a shoreline stroll feel like a plod through hot butter.

Now add to that list: Rockwall is home to the middle-school winners of NPR’s fourth-annual Student Podcast Challenge.

Their entry, The Worlds We Create, is a funny and sneakily thoughtful exploration of what it means that so many teens today are “talking digitally,” instead of face-to-face. It was one of two winning entries (the high school winner is here) chosen by our judges from among more than 2,000 student podcasts from around the country.

The team behind the pod

Rockwall hugs the eastern shore of the lake and got its name from a wall-like thread of sandstone that unspools beneath the town. “Every street name sounds the same: Lakeshore, Club Lake, Lakeview, Lakeside, and so on…” says the podcast’s narrator, 8th-grader Harrison McDonald. “If it sounds like our town is boring, that’s because it is. But let’s zoom into the center of one of those neighborhoods, on Williams Middle School.”

That’s where Harrison, fellow 8th-grader Blake Turley and 7th-graders Kit Atteberry and Wesley Helmer made the podcast, as part of librarian Misti Knight’s broadcasting class. Knight began teaching Harrison and Blake last year, when they would make videos for the school’s morning announcements. “But then I realized how good [the boys] were, and so I would say this year, I’m honestly more their manager,” she laughs.

Middle school winners Harrison McDonald, Wesley Helmer, Kit Atteberry, and Blake Turkey pose with librarian Misti Knight.

Cooper Neill for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Cooper Neill for NPR

Middle school winners Harrison McDonald, Wesley Helmer, Kit Atteberry, and Blake Turkey pose with librarian Misti Knight.

Cooper Neill for NPR

Meaning, often Ms. Knight just gives the boys the roughest of ideas and encourages them to get creative. Which is why, when Harrison came to her with an idea for NPR’s Student Podcast Challenge, she said, “Why not?”

Harrison’s interest in the contest surprised no one. He wears chunky headphones around his neck every day, like a uniform, and says he was raised on public radio. “[My family] have a system. On long road trips, we listen to This American Life. On shorter road trips, we listen to Wait, Wait, Don’t Tell Me.”

Kit also brought a love of podcasting to the effort: “My dad got me into listening to podcasts, and we would just listen to them in the car and listen to them in the house. You know, he never really got into music. He was mostly into podcasts,” Kit says, especially The Moth.

For their entry, Harrison, Kit and the team wanted to explore how students at Williams Middle School, and likely every other middle and high school in the country, interact on social media. Specifically, when they go on a platform like TikTok or Instagram and create anonymous accounts to share things about school and their classmates.

“People feel anonymous, so they feel like they can do whatever they want”

For example: An account dedicated to pics of students considered “hot.”

“My friend was on there,” Blake says, “and I texted him, ‘Hey, do you know that you’re on this Instagram account?’ And he’s like, ‘What?!’ “

Most of these accounts “aren’t even gossip,” Blake adds, “they’re just pictures of people sleeping, eating, acting surprised, acting sad.”

One account was dedicated entirely to pictures of students sleeping in class. On some accounts, students are in on the joke, but often they’re not, Harrison says.

“Through the internet … people feel anonymous, so they feel like they can do whatever they want — and get likes for it without any punishment.”

The boys found at least 81 of these accounts at Williams alone. Then they got a bold idea.

Fake it till you make it

“After seeing all of these social media pages, we decided it would be fun if we just made our own profile and posted fake gossip to see the impact it has and how it spreads through a middle school,” they explain in the podcast.

Fake gossip is putting it mildly.

“We knocked on our school police officer’s door and asked if he would pretend to arrest one of our A-V club members for the camera. Surprisingly, he actually agreed,” Harrison says.

It was the first video to go up on their new gossip account. “We didn’t think it would actually get anywhere, but less than 15 minutes later, we heard people starting to talk about it.”

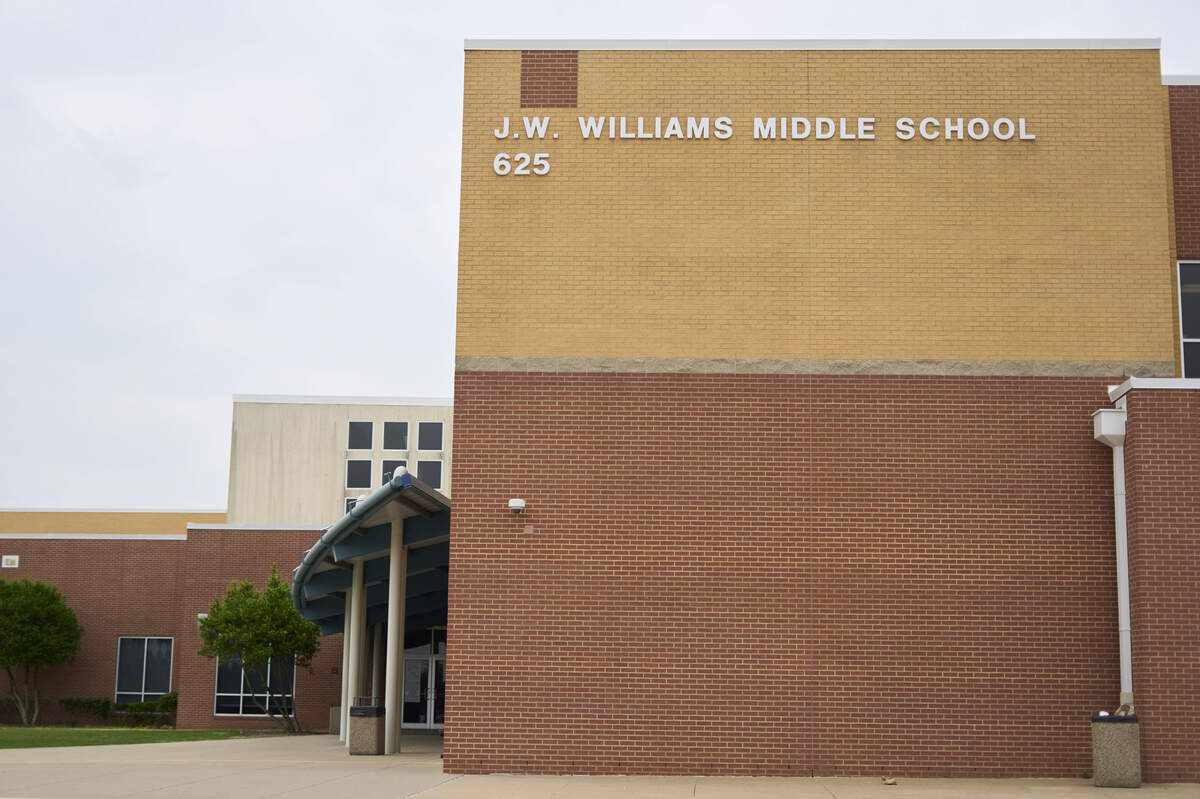

Williams Middle School in Rockwall, Texas.

Cooper Neill for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Cooper Neill for NPR

Williams Middle School in Rockwall, Texas.

Cooper Neill for NPR

Next up: The boys staged a fight in the band room, hoping a shaky camera and sound effects added in post-production would convince their classmates it was bigger and very real.

“Some of us would have kids walking up to us daily to tell us how we got absolutely destroyed in that fight or how they didn’t know we were in band. We were having fun with it now,” Harrison says in the podcast. “It didn’t take long for our fake account to start getting more followers than any other gossip account we could find.”

“Our generation prefers talking digitally”

As a social experiment, these four middle-schoolers went from quiet observers of social media to the school’s master muckrakers – even though everything they posted was utterly fake. In that way, the podcast works as a warning about the importance of media literacy — at a time when Americans half-a-century their senior are being suckered by social media every day.

But the podcast isn’t just a scold about fake news. It’s also about how, for kids their age, this is communication.

“We don’t pass notes, we send texts with our phones hidden under our desks,” Harrison says. “We don’t tell people about incidents that happened in class, we post it on TikTok. Our generation prefers talking digitally with each other from a distance, [rather] than communicating with each other in the real world.”

The boys named their podcast, The Worlds We Create.

Ms. Knight, a veteran teacher, says she’s seen these changes in students over the years.

An interior view of Williams Middle School in Rockwall, Texas.

Cooper Neill for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Cooper Neill for NPR

An interior view of Williams Middle School in Rockwall, Texas.

Cooper Neill for NPR

“I just think there’s a lot less talking and a lot more, you know, swiping through their phone instead of saying, ‘Hey, guess what I saw today?’ “

Knight has even seen it in her own family. “I would talk to my husband about, ‘Oh, did you see our eldest daughter?’ She lives in California. ‘She did this or whatever.’ And he would say, ‘How do you know this?’ “

Her answer: “‘Because I’m following her social media and her friends’ social media.’ Because if you don’t do that, she’s probably not going to pick up the phone and call us and tell us.”

Is that inherently bad? Knight says, no, not necessarily. She does get to see more of what her daughters and her friends, far and wide, are doing.

The boys’ views are similarly complicated. All this “talking digitally” can be a real “curse” for teens, they say, especially when it hurts or excludes others. But it doesn’t have to be that way.

After all, the boys say, the whole purpose of technologies from radio to the telephone, TV to the internet, has always been to help us feel less alone and more connected – by helping us create worlds – and build communities – bigger than the ones we’re born into.

[ad_2]

Source link