[ad_1]

The UK will celebrate the 70th anniversary of Queen Elizabeth II’s accession to the throne with a public holiday in a couple of weeks. Britain has changed in many ways since 1952 — the empire has been unstitched and society has become more tolerant — but inflation is running at much the same rate.

Metrics and data collection methods have been through multiple iterations. So too have the 700-odd components that make up price indices. The 1950s shopping basket — very probably a wicker one — contained foodstuffs such as ox liver, lard, canned fruit and veritable shoals of fish. Rationing, which lingered on after the end of the second world war, kept some goods out of that receptacle. A prevailing culture of thrift meant many more relied on home-grown vegetables.

Import restrictions were an issue and food price rises outpaced those in wage packets. That nasty state of affairs meant households were spending a third of their net income on food.

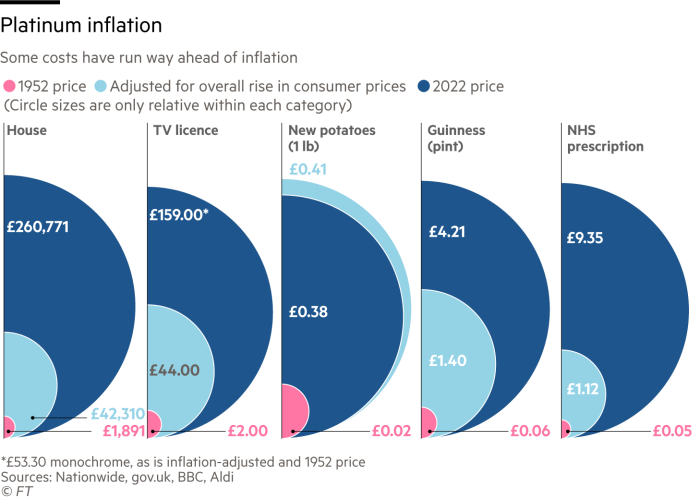

Today, the figure is 10 per cent, and larders are infinitely more varied, including such items as vegetarian sausages. That is the result of rising living standards, intensive farming and the muscle of supermarkets. Adjusting for inflation, new potatoes cost much the same as they did at the time of the coronation.

Some goods and services are cheaper. Thanks to technology, a lot less money goes on keeping in touch: WhatsApp and other apps have supplanted trunk calls. In telecoms, postwar costs were rising faster than today’s iPhones, though reasonably so, reckoned the then Earl De La Warr. “I do not know how many of your Lordships are engaged in trade or industry,” he appealed to the House of Lords. “But I should like to know how many of you are selling goods at only 50 per cent above prewar [prices].”

Other purchases have galloped ahead. Leading the pack: houses and school fees. The Nationwide house price index puts the average price of a house in 1952 at under £2,000. Today it is comfortably in excess of £250,000. That is more than six times the inflation-adjusted equivalent and will barely buy you a shoebox-sized apartment in London.

For sure, more people are better off. A fifth of the workforce now fills professional jobs, up from about 8 per cent in the 1950s. Automation also means fewer clerical jobs, down from one in eight to one in 10. But wealth remains unequally divided. As historian John Burnett put it, “poverty persists in the midst of general plenty”. Chances are this will remain the case when the next 70 years are up too.

The Lex team is interested in hearing more from readers. Please give us your view on inflation — preferably over the very long term — in the comments section below.

[ad_2]

Source link