[ad_1]

Can Fighting Save Your Marriage?

Can Fighting Save Your Marriage?

Legendary therapist Terry Real wants you to fight with your spouse. That’s not to say he’s encouraging screaming matches at the dinner table. But what can kill a relationship, he says, is when couples stop facing off because the fight doesn’t seem worth it. They may tell themselves they’re compromising or accepting what they can’t change, but they’re really settling—and over time, their resentment builds into a powder keg.

What Real encourages couples to do is bridge the gap between silent resentment and major blowouts: There’s a more skilled (and perhaps more elegant) way of fighting that not only resolves tension and conflict but also builds greater intimacy. And it has the power to transform a relationship that’s on the brink.

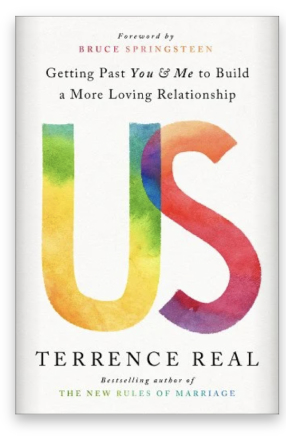

In his new book from goop Press, Us: Getting Past You & Me to Build a More Loving Relationship, Real investigates why we get stuck in patterns of conflict avoidance. The story, as he tells it, is bigger than any single relationship.

A Q&A with Terry Real

Couples who don’t fight wind up divorced because of the unprocessed issues and tension that are eating one of them—if not both of them—alive. They’re sitting on it and festering, and that’s pulling them away from intimacy and connection.

They do so for a very good reason: When they do lean into each other, it doesn’t go well. It’s “Every time I talk to so-and-so about sex, they just get defensive and angry” or “Every time I talk about parenting, my partner insists that her way is the right way and I’m an idiot.”

But here’s the thing: When it doesn’t go well, what do we do? We immediately blame our partners. We assume that person just doesn’t have it in them to listen and negotiate this issue. Then we back off—because you know Harry, you don’t want to set off Harry. And we learn to give up and not deal with whatever problem we’re facing.

Resentment. If you have a shred of resentment about something in your relationship, lean in and fight for what you want and need and are going to accept. You have to be dead honest with yourself.

I believe in something called fierce intimacy: the capacity to take each other on, to deal with what’s bothering you, to grab your partner by the collar and say, “Look, man, you, you’d better pay attention to this. It’s really important to me.”

“A healthy, passionate relationship demands a willingness to put it at risk—and not just once or twice but over and over again.”

Good couples regulate each other. Good couples will say, “Excuse me. Take your foot off my neck. I don’t like it.” They’re either pulling you in or moving you out all day long.

A healthy, passionate relationship demands a willingness to put it at risk—and not just once or twice but over and over again. No means no. If you cheat on me, you’re toast. If you don’t get into rehab, we’re over. “No” means that you have realistic limits that are not going to be transgressed.

“No” is not unhealthy. The idea that romantic partners should give each other unconditional love is bullshit. Adults don’t love each other unconditionally; adults love children unconditionally. Any adult can behave in ways egregious enough that they will close the heart of their partner. That is normal. And that is why, in a relationship, we have to behave in a way that sustains the closeness and the intimacy between us.

Our relationships are a microcosm of the society we live in—and we live in an anti-relational, narcissistic, addictive, consumerist, selfish society. The book Us is in large part a critique of what I call the toxic culture of individualism: It’s me versus you, win or lose. Our whole life is framed as a power struggle. That’s the way most of us approach our relationships. And it doesn’t work.

It takes relational skill to love your partner and stand up for yourself in the same breath. I call that soft power, or loving power. In our culture, we’re not taught how to stand up for ourselves and cherish our relationships at the same time.

“In our individualistic culture, our relationship to relationships is passive. You get what you get, and then you complain about it.”

Look at the difference between saying, “Don’t talk to me like that” and saying, “Honey, I want to hear what you have to say. Could you tone it down so I can listen?” It’s two ways of saying the same thing, but one is totally flat-footed and the other is skillful.

We don’t teach relationship skills to people, but our ambition for relationships couldn’t be larger. We’ve never wanted more from our relationships than we do now. We want to be lifelong lovers, but we simply don’t have the chops. We don’t have the skills to pull off such a tremendous ambition. You have to know what you’re doing.

In our individualistic culture, our relationship to relationships is passive. You get what you get, and then you complain about it. That has to be the worst behavioral programming I’ve ever heard of. I want people to be more proactive on the front end and less resentful on the back end. So I talk about three phases of getting more of what you want in a relationship.

The first phase: Daring to rock the boat. This is the assertive phase. This is where you grab your partner by the collar say, “You’d best pay attention. This is important.”

Once your partner listens, it’s time for the second phase: Helping them win. Drop the sword and shield, roll up your sleeves, and teach them. Not because you’re the expert on relationships but because you’re the expert on you. This is what I would like. You have to speak with humility: “This is what would work for me for the next 10 minutes. I need to vent about a fight I just had. Don’t try to give me advice; just be nice about my feelings. Would you give that to me?”

And then the third phase: Making it worth their while. I teach people to celebrate the glass 15 percent full when it was only 5 percent full last week. Work as a team: What do we need to do to get this glass 20 percent full today? You say, “I really like what you’re doing. You’re trying to come through for me. How can I help you do that?”

Yeah, if it’s a micro backing off. If it’s “I don’t want to talk about this right now, Tuesday at 3 o’clock.” If that’s how they’re backing off, let them have their way. You didn’t get it Tuesday at 3 o’clock. I call that having a micro disappointment. In that case, keep your micro disappointment micro. Don’t jump to “He never does this and always does that, and it’s just who he is.” Don’t do all that. You’re just disappointed in this moment.

If you can never get anything out of the person because they live behind walls and they’re disengaged—and no matter what you do, you can’t get through to them—that is a flag to go see a therapist.

It comes down to one question: Am I getting enough in this relationship to make grieving what I’m not getting worth my while?

If the answer is no, drag that person to a therapist. If the therapist doesn’t help, try a different therapist. And if no therapist helps, then you’re done. Leave. But if the answer is yes—”Our sex life sucks, and our parenting isn’t what I want it to be, and we don’t have the money I wish we had, but oh my gosh, I get so much else”—embrace what you are getting, feel the pain of what you’re not getting, and be with it.

Related Reading on goop

Terrence Real is an internationally recognized family therapist, speaker, and author. He founded the Relational Life Institute, offering workshops for couples, individuals, and parents, along with a professional training program for clinicians to learn his Relational Life Therapy methodology. In addition to Us: Getting Past You & Me to Build a More Loving Relationship, he is the bestselling author of I Don’t Want to Talk About It, How Can I Get Through to You?, and The New Rules of Marriage.

We hope you enjoy the books recommended here. Our goal is to suggest only things we love and think you might, as well. We also like transparency, so, full disclosure: We may collect a share of sales or other compensation if you purchase through the external links on this page.

[ad_2]

Source link