[ad_1]

For more than five years after launching the personal finance app Truebill with his two brothers, Yahya Mokhtarzada watched the subscription economy grow.

But now that trend has gone into reverse as rising inflation causes consumers to rethink their discretionary spending — a development that Mokhtarzada, like investors and analysts, believes will spread far beyond their Netflix accounts.

“As long as there is this much uncertainty in the economy, people are going to be increasingly cautious with their money,” said Maryland-based Mokhtarzada, whose app manages subscriptions, bills and other payments.

Last year Mokhtarzada noticed that the app’s 2.5mn users were scrapping more subscriptions, ranging from streaming services to meal kits. By March the cancellations were outnumbering new sign-ups.

This week Netflix’s share price dropped more than 35 per cent after it reported a fall in subscriber numbers for the first time in a decade. While Netflix suffered from increased competition, Steve Wreford, a portfolio manager at Lazard Asset Management, says the squeeze on disposable incomes acted as a catalyst.

“What’s happening with the streaming services is the canary in the coal mine,” he said. “Inflation puts pressure on the consumer, you think about which is your least valued purchase, and you then find out which businesses are really going to struggle in that inflationary environment.”

Inflation has gathered pace just as consumers were resuming aspects of their pre-pandemic lives — eating out, working from the office and booking vacations. It also comes after Covid-19 restrictions pushed up savings rates: Americans had built up an extra $4.2tn of cash by the end of 2021, according to the Federal Reserve.

Yet price rises and worries over the war in Ukraine, which has worsened inflation, have led to a marked decline in consumer sentiment, said Jessica Moulton, a senior partner at McKinsey.

“Consumers’ levels of optimism are back to mid-2020 levels. That’s a big drop from the autumn,” she said, citing McKinsey surveys carried out in five European countries and the US.

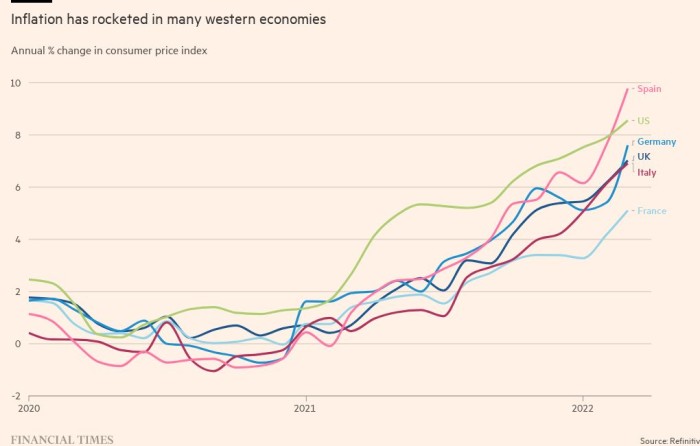

UK retail sales fell 1.4 per cent in March, the second consecutive monthly decline, as surging inflation began to bite. Inflation of 7 per cent — the rate in Germany in March — effectively cuts household discretionary spending there by 13 per cent, according to a McKinsey analysis.

The gloomier climate has cast a shadow over sectors like clothing and restaurants, said Wreford. Investors are taking note: global consumer discretionary stocks have fallen 14 per cent since the start of the year, against 8 per cent for the broader MSCI World index, according to Bloomberg data. Apparel groups’ shares have been particularly hit.

The London-based online clothing retailer Asos this month reported a sharp fall in sales growth and profits, and warned that pressure on incomes might outweigh the boost expected to accompany the loosening of Covid restrictions. Its shares are down almost 40 per cent since the start of the year.

Asos chief executive Mat Dunn said that “rising energy prices and food inflation will weigh on discretionary spend. The next three months will be telling as we see how these factors play out on consumer discretionary income.”

Swedish rival H&M last month also reported a sudden slowdown in sales growth. Spending on apparel has dropped below 2019 levels in the UK, according to data provider Fable.

This year’s inflationary squeeze differs from past periods of rising prices, in following on the heels of the pandemic. Consumers’ lifestyles are already in flux as they emerge from Covid-19 restrictions. Now inflation has added to pressure on companies that gained from lockdowns, like Netflix and Peloton, which have also had to raise their own prices.

The inflationary environment has damped post-Covid optimism at groups like Asos that still hope to benefit from a “summer of events, parties and weddings”, in the words of Dunn.

Restaurants hoping for a recovery are wrestling with demands for higher wages from their own staff, while the chief executive of a London-based casual dining chain said that average spend per customer had already declined in the past month.

But the same does not so far appear true of the travel industry, where consumers with accumulated savings look determined to spend them on trips they missed during the height of the pandemic.

“Normally [in an inflationary environment] we would see an impact on travel, but there is a lot of pent-up demand,” said Moulton.

American Airlines and Delta Air Lines, the US’s largest and third-largest carriers by fleet size, reported record ticket sales in March, while United Airlines, the second largest, predicted that the second quarter would be its most profitable ever.

“We’re seeing no signs of any customer reticence around inflation,” Ed Bastian, Delta chief executive told the Financial Times, while Robert Isom, American chief executive, told employees this week that “demand is as strong as we’ve ever seen it”.

Will Hayllar, managing partner at strategy consultants OC&C, said that the impact of the income squeeze was not entirely predictable. “Consumers want some things that they feel good about. It doesn’t work out as completely utilitarian,” he said.

Food delivery services, another beneficiary of the pandemic, so far maintain they are not suffering from the pressure on consumer spending.

$4.2tn

Extra savings built up by Americans by the end of 2021

Deliveroo maintained its annual guidance for order volume growth in a trading update this month, saying it would be slower than 2021’s 70 per cent but still growing by 15-25 per cent on a constant currency basis.

Jitse Groen, chief executive of Just Eat Takeaway, insisted this week that food price inflation could be a net benefit: when restaurants’ prices go up, so too does Just Eat’s commission.

But David Reynolds, analyst at Irish investment bank Davy, said: “We are moving into uncharted territory. Ordinarily online takeaway food proves to be fairly resilient in the face of inflationary pressures and dining out bears the brunt.

“But with double-digit inflation not impossible, there must be risks that consumers drop some or all takeaway food orders.”

Analysts agree that inflation has not yet peaked, and that its full impact is only just starting to be felt. While pandemic savings will cushion some wealthier consumers for a time, those on lower incomes will be the first to feel the squeeze as staples account for a higher proportion of their disposable incomes, said Wreford.

Makers of branded consumer staples have so far succeeded in passing price rises on to consumers: Nestlé, Heineken, Danone and Procter & Gamble all said this week they had increased prices by about 5 per cent in the three months to March, without pushing down sales.

But as the pressure grows, households may switch to private-label products. “Consumer down-trading is looking increasingly likely as discretionary spend gets squeezed . . . Premium brands will likely hold up, as will value, but ‘me too’ mass brands are at risk,” said Warren Ackerman, analyst at Barclays.

Some businesses hope to benefit from consumers seeking cheap alternatives.

Mooky Greidinger, chief executive of Cineworld, the world’s second largest cinema chain, is betting that cinemas, unlike Netflix, will benefit from lower discretionary spend: “In view of recession [consumers] cannot afford the same trips abroad or a £100 ticket musical but they can afford a £10 ticket to the cinema. I’m not worried at all,” he told the FT last month.

At the opposite end of the scale, fund managers expect luxury goods makers to weather the storm, as their margins are high and wealthy buyers cushioned from inflation’s worst effects.

Groups such as France-based LVMH “have consistently been able to raise prices to more than offset the inflationary pressures”, said Marcus Morris-Eyton, fund manager at Allianz.

Yet Mokhtarzada said Truebill’s customer base, which slants towards younger users, has already shown a marked cut in spending: on both petrol and groceries, the rise in total spending has lagged behind the rises in prices, indicating a more prudent approach. “That has to indicate a change in consumer behaviour,” he said.

Reporting by Tim Bradshaw, Steff Chávez, Alice Hancock, Patrick Mathurin and Patricia Nilsson

[ad_2]

Source link