[ad_1]

The U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) announced in a February 2022 statement that it had successfully seized the majority of the bitcoin drained in a 2016 hack of the cryptocurrency exchange Bitifinex after gaining control of the wallet supposedly containing the stolen funds.

Despite the apparent unlikelihood of retaking long-gone funds, a complex but deterministic trail of evidence allowed law enforcement to catch Ilya Lichtenstein and Heather Morgan, a couple that was allegedly trying to obfuscate the illegal origins of the bitcoin they had been leveraging to flex shiny lifestyles through a complex money laundering scheme.

But what seemed to be a carefully-thought-out scam actually turned out to be a quite fragile one filled with missteps, which facilitated the work of special agent Christopher Janczewski, assigned to the Internal Revenue Service’s criminal investigation unit (IRS-CI). This work ultimately led to Janczewski filing a complaint with judge Robin Meriweather to charge Lichtenstein and Morgan for money laundering conspiracy and conspiracy to defraud the United States.

This article takes a deep dive into the nuances of the law enforcement work that uncovered the identities of the accused Bitfinex hackers, and into the steps of the charged couple, relying on the accounts provided by the DOJ and special agent Janczewski. However, since crucial aspects of the investigation have not been disclosed by official documents, the author will provide plausible scenarios and possible explanations to questions that remain unanswered.

How Did Law Enforcement Seize The Stolen Bitfinex Bitcoin?

Bitcoin proponents often boast about the monetary system’s set of principles that enables a high degree of sovereignty and resistance to censorship, making Bitcoin transactions impossible to be stopped and bitcoin holdings impossible to be seized. But, if that is true, how then was law enforcement able to take a hold of the launderers’ bitcoin in this case?

According to the complaint filed by special agent Janczewski, law enforcement was able to get inside Litchestein’s cloud storage where he kept much if not all of the sensitive information related to his operations as he attempted to clean the dirty funds — including the private keys of the Bitcoin wallet holding the largest portion of stolen BTC.

The censorship resistance of Bitcoin transactions and the sovereignty of bitcoin funds depend on the proper handling of the associated private keys, as they are the only way to move bitcoin from one wallet to another.

Even though Lichtenstein’s private keys were kept in cloud storage, according to the DOJ they were encrypted with a password so long that even sophisticated attackers would probably not have been able to crack it in their lifetime. The DOJ did not respond to a request for comment on how it was able to decrypt the file and access the private keys.

There are a few plausible scenarios for how law enforcement was able to crack Lichtenstein’s encryption. Though not insecure in and of itself, symmetric encryption, which leverages an encryption password for both encrypt and decrypt functions, is only as secure as its password and that password’s storage.

Therefore, the first possibility relates to the security of the password’s storage; law enforcement could have obtained access to the password somehow and didn’t need to brute force its way through the files in the cloud. An alternative method for law enforcement being able to decrypt Lichtenstein’s files could involve it having so much more personal information about the couple and computing power than any other sophisticated attacker in the world that a tailored attack to decrypt targeted files could actually be viable while not contradicting the DOJ’s statements. We also don’t know the algorithm used in the encryption scheme — some are more robust than others and variations in the same algorithm also pose different security risks — so the specific algorithm used might have been more susceptible to cracking, although this would contradict the DOJ claims regarding crackability above.

The most likely case of the three is arguably that law enforcement didn’t need to decrypt the file in the first place, which makes sense, especially given the DOJ comments above. Special agent Janczewski and his team could have gained access to the password somehow and wouldn’t need to brute force its way through the cloud storage’s files. This could be facilitated by a third party that Lichtenstein entrusted with the creation or storage of the decryption password, or through some sort of misstep by the couple that led to the password being compromised.

Why Keep Private Keys On Cloud Storage?

The reason why Lichtenstein would keep such a sensitive file in an online database is unclear. However, some speculation relates to the underlying hack — an act for which the couple has not been charged by law enforcement — and the need for having the wallet’s private keys kept on the cloud “as this allows remote access to a third party,” according to a Twitter thread by Ergo from OXT Research.

The cooperation assumption also supports the case for symmetric encryption. While asymmetric encryption is well designed for sending and receiving sensitive data — as the data is encrypted using the recipient’s public key and can only be decrypted using the recipient’s private key — symmetric encryption is perfect for sharing access to a stationary file as the decryption password can be shared between the two parties.

An alternative reason for keeping the private keys online would be simple lack of care. The hacker could simply have thought their password was secure enough and fell for the convenience of having it on a cloud service that can be accessed anywhere with an internet connection. But this scenario still doesn’t answer the question of how the couple got access to the private keys related to the hack.

Keeping the private key online for convenience makes sense, provided the hackers lacked sufficient technical knowledge to ensure a strong enough symmetric encryption setup or simply assumed their arrangement couldn’t be breached.

Bitfinex declined to comment on any details known about the hacker or whether they are still being tracked down.

“We cannot comment on the specifics of any case under investigation,” Bitfinex CTO Paolo Ardoino told Bitcoin Magazine, adding that there are “inevitably a variety of parties involved” in “such a major security breach.”

How Did Lichtenstein And Morgan Get Caught?

The complaint and DOJ’s statement alleges that the couple employed several techniques to attempt to launder the bitcoin, including chain hopping and the use of pseudonymous and business accounts at several cryptocurrency exchanges. So, how did their movements get spotted? It mostly boils down to patterns and similarities paired with carelessness. Bitfinex also “worked with global law enforcement agencies and blockchain analytics firms” to help recover the stolen bitcoin, Ardoino said.

Lichtenstein would often open up accounts on bitcoin exchanges with fictitious identities. In one specific case, he allegedly opened eight accounts on a single exchange (Poloniex, according to Ergo), which at first were seemingly unrelated and not trivially linkable. However, all of those accounts shared multiple characteristics that, according to the complaint, gave the couple’s identity away.

First, all of the Poloniex accounts used the same email provider based in India and had “similarly styled” email addresses. Second, they were accessed by the same IP address — a major red flag that makes it trivial to assume the accounts were controlled by the same entity. Third, the accounts were created around the same time, close to the Bitfinex hack. Additionally, all accounts were abandoned following the exchange’s requests for additional personal information.

The complaint also alleges that Lichtenstein joined multiple bitcoin withdrawals together from different Poloniex accounts into a single Bitcoin wallet cluster, after which he deposited into an account at a bitcoin exchange (Coinbase, according to Ergo), for which he had previously provided know-your-customer (KYC) information.

“The account was verified with photographs of Lichtenstein’s California driver’s license and a selfie-style photograph,” per the complaint. “The account was registered to an email address containing Lichtenstein’s first name.”

By assuming that he had already cleansed the bitcoin, and sending it to a KYC’d account, Lichtenstein undid the pseudonymity the previous accounts had accomplished with India-based email accounts, as he hinted to law enforcement that he owned the funds from those initial withdrawals that were clustered together. And the complaint alleges that Lichtenstein also kept a spreadsheet in his cloud storage containing detailed information about all eight Poloniex accounts.

When it comes to on-chain data, Ergo told Bitcoin Magazine that it is impossible for a passive observer to assess the validity of many of the complaint’s claims since the darknet marketplace AlphaBay was used early on as a passthrough.

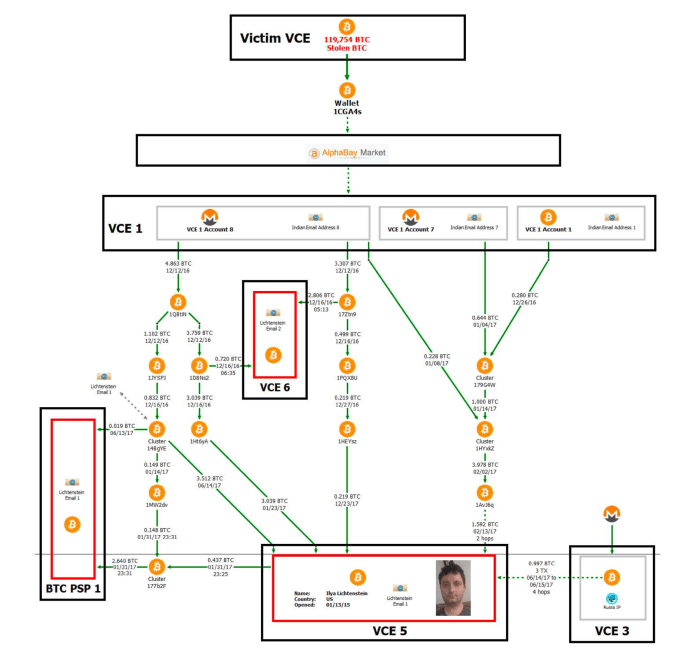

The complaint details the flow of funds after the Bitfinex hack, but the AlphaBay transaction information isn’t auditable by outsider observers, who therefore cannot trace the funds themselves. Image source: DOJ.

“The investigation is very straight-forward, but it requires insider knowledge of cross-custodial entity flows,” Ergo told Bitcoin Magazine. “For example, the [U.S. government] and chain surveillance firms have shared the AlphaBay transaction history which has no real on-chain fingerprint and we don’t have access to that information. That’s about where I have to stop any analysis as a passive observer.”

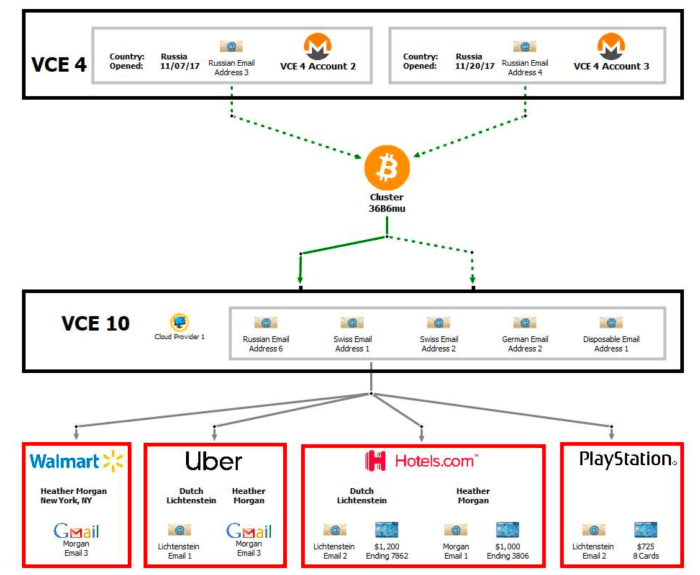

Another key piece of information is wallet cluster “36B6mu,” which was formed by bitcoin withdrawals from two accounts at Bittrex, according to Ergo, which had been entirely funded by Monero deposits. Wallet cluster 36B6mu was then used to fund different accounts at other bitcoin exchanges, which, although it did not contain KYC information on the couple, according to the complaint, five different accounts at the same exchange used the same IP address, hosted by a cloud provider in New York. As the provider handed its records to law enforcement, it was identified that that IP was leased by an account in the name of Lichtenstein and tied to his personal email address.

The couple assumed that by funding an exchange account with Monero and withdrawing BTC they would have “clean” funds, however, a subsequent trail of KYC information was used to deanonymize their fictitious identities across different custodial services. Image source: DOJ.

Ergo said the OXT team wasn’t able to validate any claims about the 36B6mu cluster.

“We searched for the 36B6mu address that would correspond to the cluster and found a single address,” Ergo said, sharing a link to the address found. “But the address is not part of a traditional wallet cluster. Further, the timing and volumes don’t seem to correspond with those noted in the complaint.”

“Maybe it’s a typo? So we weren’t able to really validate anything to do with the 36B6mu cluster,” Ergo added.

Bitcoin Privacy Requires Intention — And Attention

Aside from the sections that cannot be independently attested by external observers, after analyzing the complaint, it becomes clear that Lichtenstein and Morgan deposited different levels of trust in their setup and in several services as they allegedly attempted to use the bitcoin from the hack.

First and foremost, Lichtenstein and Morgan maintained sensitive documents online, in a cloud storage service susceptible to seizure and subpoenas. This practice increases the chances that the setup could be compromised, as it makes such files remotely accessible and deposits trust in a centralized company — which is never a good idea. For hardened security, important files and passwords should be kept offline in a secure location, and preferably spread out in different jurisdictions.

Trust compromised most of the couple’s efforts in moving the bitcoin funds. The first service they trusted was the huge darknet market AlphaBay. Though it is unclear how law enforcement was able to spot their AlphaBay activity — even though the darknet market has suffered more than one security breach since 2016—– the couple nonetheless seems to have assumed this could never happen. But perhaps most importantly, darknet markets often raise suspicion and are always a primary focus of law enforcement work.

Assumptions are dangerous because they can lead you to drop down your guard, which often triggers missteps which a savvy observer or attacker can leverage. In this case, Lichtenstein and Morgan assumed at one point that they had employed so many techniques to obfuscate the source of funds that they felt safe in depositing that bitcoin into accounts possessing their personally-identifiable information — an action that can ensue a cascading, backwards effect to deanonymize most if not all of the previous transactions.

Another red flag in the couple’s handling of bitcoin relates to clustering together funds from different sources, which enables chain analysis companies and law enforcement to plausibly assume the same person controlled those funds — another backwards deanonymization opportunity. There is also no record of using mixing services by the couple, which can’t erase past activity, but can provide good forward-looking privacy if done correctly. PayJoin is another tool that can be leveraged to increase privacy when spending bitcoin, though there is no record of the couple using it.

Lichtenstein and Morgan did attempt to do chain hopping as an alternative for obtaining spending privacy, a technique that attempts to break on-chain fingerprints and thus, heuristic links. However, they performed it through custodial services — mostly bitcoin exchanges — which undermine the practice and introduce an unnecessary trusted third party that can be subpoenaed. Chain hopping is properly conducted through peer-to-peer setups or atomic swaps.

Lichtenstein and Morgan also tried using pseudonymous, or fictitious, identities to open accounts at bitcoin exchanges to conceal their real names. However, patterns in doing so led observers to become more aware of such accounts, while an IP address in common removed doubts and enabled law enforcement to assume the same entity controlled all of those accounts.

Good operational security generally requires that each identity be completely isolated from others by using its own email provider and address, having its own unique name and most importantly, using a separate device. Commonly, a robust setup will also require each different identity to use a different VPN provider and account that does not keep logs and does not have any ties to that user’s real world identity.

Since Bitcoin is a transparent monetary network, funds can easily be traced across payments. Private use of Bitcoin, therefore, requires knowledge about the functioning of the network and utmost care and effort over the years to ensure the littlest amount of missteps as possible while abiding by clear operational guidelines. Bitcoin isn’t anonymous, but it isn’t flawed either; use of this sovereign money requires intention — and attention.

What Will Happen To The Recovered Bitcoin?

Although the couple have been charged with two offenses by U.S. law enforcement, there will still be a judging process in court to determine whether they are found guilty or not. In the event that the couple is found guilty and the funds are sent back to Bitfinex, the exchange has an action plan, Ardoino told Bitcoin Magazine.

“After the 2016 hack, Bitfinex created BFX tokens, and gave them to affected customers at the rate of one coin for each $1 lost,” Ardoino said. “Within eight months of the security breach, Bitfinex redeemed all the BFX tokens with dollars or by exchanging the digital tokens, convertible into one common share of the capital stock of iFinex Inc. Approximately 54.4 million BFX tokens were converted.”

Monthly redemptions of BFX tokens started in September 2016, Ardoino said, with the last BFX token being redeemed in early April of the following year. The token had begun trading at roughly $0.20 but gradually increased in value to almost $1.

“Bitfinex also created a tradeable RRT token for certain BFX holders that converted BFX tokens into shares of iFinex,” Ardoino explained. “When we successfully recover the funds we will make a distribution to RRT holders of up to one dollar per RRT. There are approximately 30 million RRTs outstanding.”

RRT holders have a priority claim on any recovered property from the 2016 hack, according to Ardoino, and the exchange may redeem RRTs in digital tokens, cash or other property.

[ad_2]

Source link