[ad_1]

UK consumer confidence plunged in February and many measures of spending remained below pre-pandemic levels as surging living costs hit morale even before Russia invaded Ukraine.

The consumer confidence index, a closely watched indicator of how people view the state of their personal finances and wider economic prospects compiled by research company GfK, fell seven points to minus 26 in February. It was the lowest score since January 2021 and one of the worst since the start of the pandemic.

“Fear about the impact of price rises from food to fuel and utilities, increased taxation and interest rate hikes has created a perfect storm of worries that has shaken consumer confidence,” said Joe Staton, client strategy director at GfK.

Worryingly for the post-pandemic recovery, people’s view on their personal financial situation in the year ahead fell by 12 points to minus 14, the worst reading since April 2020 at the height of the first lockdown.

The Ukraine crisis could well exacerbate the squeeze on households. Jonathan Haskel, an external member of the Bank of England’s Monetary Policy Committee, said on Wednesday that the conflict created “a material risk” of further increases in global gas prices, which would add to the already considerable rises in inflation and energy prices.

Rising oil and gas prices “will exacerbate the cost of living crisis and depress gross domestic product growth”, echoed Thomas Pugh, economist at RSM UK, a business advisory company.

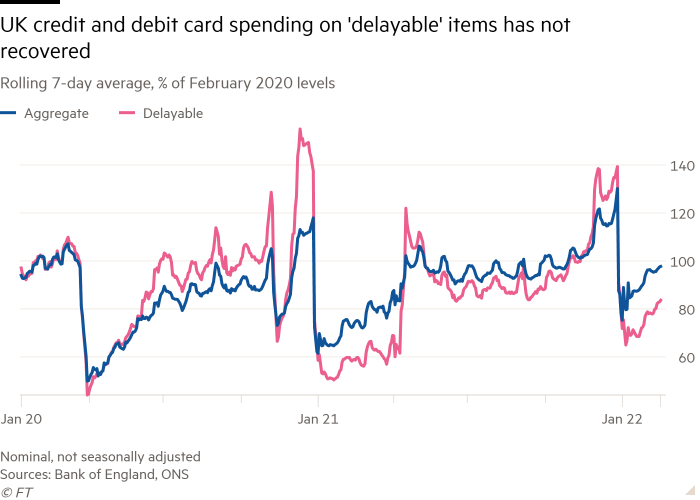

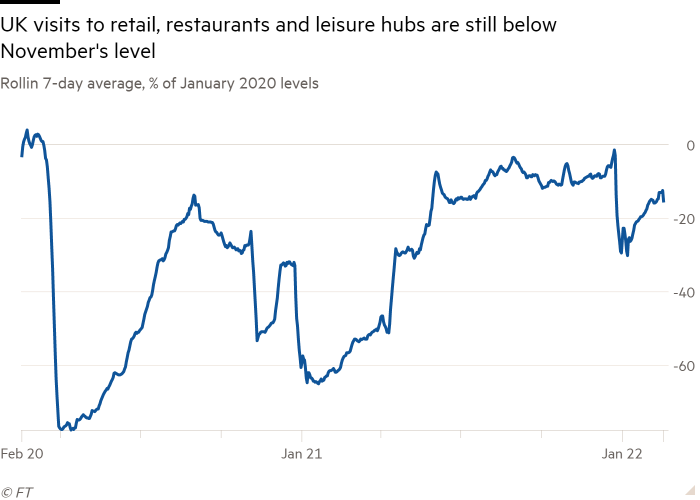

High-frequency data, such as retail footfall and credit card spending, not only remained below pre-pandemic levels, they were lower than their recent peak in November as households appeared to be heeding warnings from the BoE that they face the worst squeeze on their disposable incomes for at least 30 years as a result of surging inflation, slowing growth and higher taxes.

The data are less comprehensive and reliable than official statistics. But policymakers and analysts monitor the figures closely for a more timely measure of economic activity since official output data only cover transactions up to December, when the Omicron coronavirus wave caused gross domestic product to contract.

Official data released last week showed that retail sales in January were still 2 per cent below November’s level despite their sharp rebound in January.

Some data suggest that non-discretionary spending “is being delayed”, said Fabrice Montagne, economist at Barclays.

Credit and debit card spending on so-called delayable items, such as clothing and furnishings, rose in January and early February, but was still 17 per cent below its February 2020 level in the week ending February 17, according to BoE data. It was also well below its level from April to the end of last year, despite the removal of nearly all Covid restrictions and even with rising prices pushing up the value of nominal spending.

“We are seeing delayable spending stagnant,” said Simon Harvey, head of analysis at foreign exchange company Monex Europe. With higher living costs, “the easiest place to start tightening your belt is on discretionary spending”.

Inflation is at its highest level in 30 years and nearly half of the population who reported rising living costs said they had cut spending on non-essentials as a result, according to a regular survey by the Office for National Statistics covering the first two weeks of February.

A monthly poll published this week by the consumer company Which? showed similar findings. Rocio Concha, Which?’s director of policy and advocacy, said: “More than half of households have had to take measures to cover the cost of living, such as cutting back on energy and food or dipping into savings.” The proportion has risen sharply during the past few months.

Spending on some categories is not back to pre-pandemic levels partially because “households are increasingly concerned about rising costs”, said Yael Selfin, chief economist at advisory firm KPMG. “The risk is that consumers become overwhelmed by the triple hit of rapidly rising interest rates, higher tax burden, and rising energy costs and inflation and abruptly withdraw a large part of their non-essential spending,” she explained.

Many other economic activity measures are also far from pre-pandemic levels. Flight numbers in the week to February 22 were 38 per cent below the same period in 2019, according to Eurocontrol, the body that co-ordinates national air traffic management agencies across Europe.

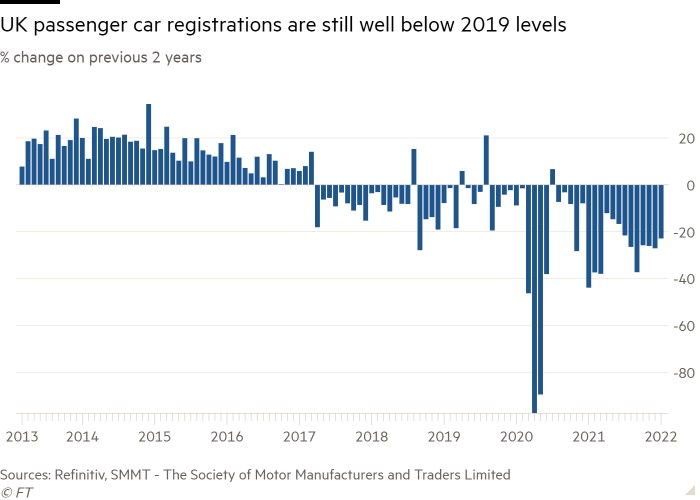

Passenger cars registrations in January were 23 per cent lower than the same month in 2019. Visits to retail outlets, bars and restaurants are 15 per cent down from their February 2020 levels and are still below where they were in the second half of last year.

Non-essential spending — such as leisure, health and beauty, and home improvement — on debit and credit cards made by Nationwide Building Society customers was 11 per cent lower in January than in November, according to the company.

One of the few bright spots is that most statistics show the economic effects of Omicron have been much milder than in previous infection waves and the recovery much quicker and more broad-based.

Visits to retail and entertainment venues and restaurants dropped for only a couple of weeks and started to recover from mid-January, according to Google mobility data.

The removal of nearly all coronavirus restrictions across most of the country and falling Covid-19 infections boosted retail footfall, credit and debit card spending and other measures of consumer activity in January and February.

With the removal of most international travel restrictions, flight numbers into and out of UK airports rose 40 per cent in the week to February 22 compared with the same week in the previous month, according to Eurocontrol.

“The impact of Omicron was smaller as it was limited to people actually catching the virus, and not the wider population,” Montagne said.

With the worst of the tax and energy price increase yet to come and the heightened geopolitical uncertainty, analysts said the consumer sector would suffer further.

“The areas that have driven the UK economy, the consumer willingness to spend and borrow, is where we are going to see the weaknesses,” Harvey said.

Andrew Goodwin, economist at Oxford Economics, was equally downbeat. “The biggest gains from social consumption recovering are behind us and the worst of the squeeze on real incomes is still to come,” he said.

[ad_2]

Source link