[ad_1]

This is an opinion editorial by Dan, cohost of the Blue Collar Bitcoin Podcast.

Series Contents

Part 1: Fiat Plumbing

Introduction

Busted Pipes

The Reserve Currency Complication

The Cantillon Conundrum

Part 2: The Purchasing Power Preserver

Part 3: Monetary Decomplexification

The Financial Simplifier

The Debt Disincentivizer

A “Crypto” Caution

Conclusion

A Preliminary Note To The Reader: This was originally written as one essay that has since been divided into three parts. Each section covers distinctive concepts, but the overarching thesis relies on the three sections in totality. Part 1 worked to highlight why the current fiat system produces economic imbalance. Part 2 and Part 3 work to demonstrate how Bitcoin may serve as a solution.

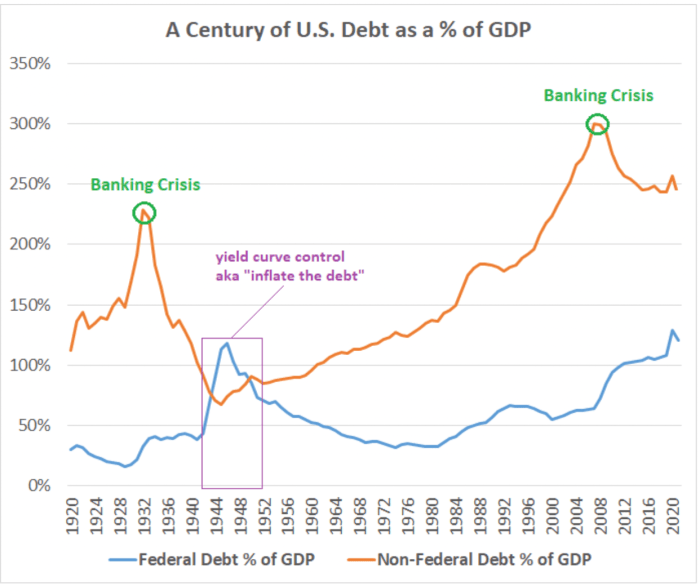

Unprecedented debt levels that exist in today’s financial system spell one thing in the long run: currency debasement. The word “inflation” is tossed around frequently and flippantly these days. Few appreciate its actual meaning, true causes or real implications. For many, inflation is nothing more than a price at the gas pump or grocery store that they complain about over wine and cocktails. “It’s Biden’s, Obama’s or Putin’s fault!” When we zoom out and think long term, inflation is a massive — and I argue unsolvable — fiat math problem that gets tougher and tougher to reconcile as decades march on. In today’s economy, productivity lags debt to such an extent that any and all methods of restitution require struggle. A key metric for tracking debt progression is debt divided by gross domestic product (debt/GDP). Digest the chart below which specifically reflects both total debt and public federal debt as relates to GDP.

(Chart/Lyn Alden)

If we focus on federal debt (blue line), we see that in just 50 years we’ve gone from sub-40% debt/GDP to 135% during the COVID-19 pandemic — the highest levels of the last century. It’s also worth noting that the current predicament is significantly more dramatic than even this chart and these numbers indicate since this doesn’t reflect colossal unfunded entitlement liabilities (i.e. Social Security, Medicare and Medicaid) that are anticipated in perpetuity.

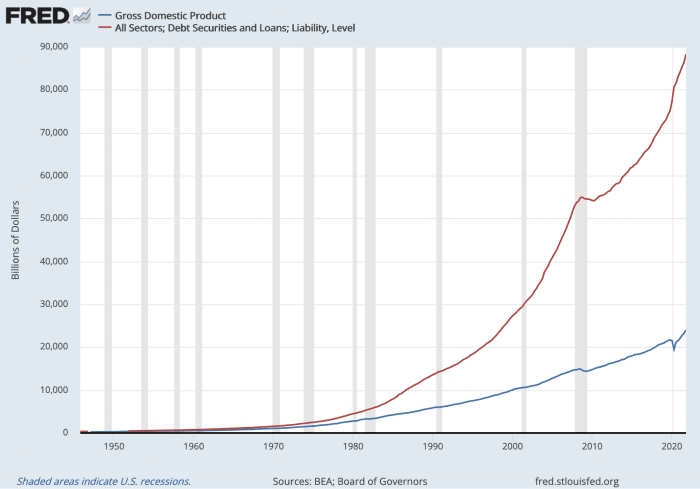

What does this excessive debt mean? To make sense of it, let’s distill these realities down to the individual. Suppose someone racks up exorbitant liabilities: two mortgages well outside their price range, three cars they can’t afford and a boat they never use. Even if their income is sizable, eventually their debt load reaches a level they cannot sustain. Maybe they procrastinate by tallying up credit cards or taking out a loan with a local credit union to merely service the minimum payments on their existing debt. But if these habits persist, the camel’s back inevitably breaks — they foreclose on the homes; SeaRay sends someone to take back the boat out of their driveway; their Tesla gets repossessed; they go bankrupt. No matter how much she or he felt like they “needed” or “deserved” all those items, the math finally bit them in the ass. If you were to create a chart to encapsulate this person’s quandary, you would see two lines diverging in opposite directions. The gap between the line representing their debt and the line representing their income (or productivity) would widen until they reached insolvency. The chart would look something like this:

(Chart/St. Louis Fed)

And yes, this chart is real. It’s a distillation of the United States’ total debt (in red) over gross domestic product, or productivity (in blue). I first saw this chart posted on Twitter by well-known sound money advocate and tech investor Lawrence Lepard. He included the following text above it.

“Blue line generates income to pay interest on red line. See the problem? It’s just math.”

The math is catching up to sovereign nation states too, but the way the chickens come home to roost looks quite different for central governments than for the individual in the paragraph above, particularly in countries with reserve currency status. You see, when a government has its paws on both the supply of money and the price of money (i.e. interest rates) as they do in today’s fiat monetary system, they can attempt to default in a much softer fashion. This sort of soft default necessarily leads to growth in money supply, because when central banks have access to newly created reserves (a money printer, if you will) it’s incredibly unlikely debt service payments will be missed or neglected. Rather, debt will be monetized, meaning the government will borrow newly fabricated money1 from the central bank rather than raising authentic capital through increasing taxes or selling bonds to real buyers in the economy (actual domestic or international investors). In this way, money is artificially manufactured to service liabilities. Lyn Alden puts debt levels and debt monetization in context:

“When a country starts getting to about 100% debt-to-GDP, the situation becomes nearly unrecoverable … a study by Hirschman Capital noted that out of 51 cases of government debt breaking above 130% of GDP since 1800, 50 governments have defaulted. The only exception, so far, is Japan, which is the largest creditor nation in the world. By “defaulted,” Hirschman Capital included nominal default and major inflations where the bondholders failed to be paid back by a wide margin on an inflation-adjusted basis … There’s no example I can find of a large country with more than 100% government debt-to-GDP where the central bank doesn’t own a significant chunk of that debt.”2

The inordinate monetary power of fiat central banks and treasuries is a large contributor to the excessive leverage (debt) buildup in the first place. Centralized control over money enables policymakers to delay economic pain in a seemingly perpetual manner, repeatedly alleviating short-term problems. But even if intentions are pure, this game cannot last forever. History demonstrates that good intentions are not enough; if incentives are improperly aligned, instability awaits.

Lamentably, the threat of harmful currency debasement and inflation dramatically increases as debt levels become more unsustainable. In the 2020s, we are beginning to feel the damaging effects of this shortsighted fiat experiment. Those who exert monetary power do indeed have the ability to palliate pressing economic pain, but in the long run it’s my contention that this will amplify total economic destruction, particularly for the less privileged in society. As more monetary units enter the system to ease discomfort, existing units lose purchasing power relative to what would have transpired without such money insertion. Pressure eventually builds up in the system to such an extent that it must escape somewhere — that escape valve is the debasing currency. Career-long bond trader Greg Foss puts it like this:

“In a debt/GDP spiral, the fiat currency is the error term. That is pure mathematics. It is a spiral to which there is no mathematical escape.”3

This inflationary landscape is especially troublesome to members of the middle and lower classes for several key reasons. First, as we talked about above, this demographic tends to hold fewer assets, both in total and as a percentage of their net worth. As the currency melts, assets like stocks and real estate tend to rise (at least somewhat) alongside money supply. Conversely, growth in salaries and wages is likely to underperform inflation and those with less free cash quickly start treading water. (This was covered at length in Part 1.) Second, middle and lower class members are, by and large, demonstrably less financially literate and nimble. In inflationary environments knowledge and access are power, and it often takes maneuvering to maintain buying power. Members of the upper class are far more likely to have the tax and investment know-how, as well as egress into choice financial instruments, to jump on the life raft as the ship goes down. Third, many average wage earners are more reliant on defined benefit plans, social security or traditional retirement strategies. These tools stand squarely in the scope of the inflationary firing squad. During periods of debasement, assets with payouts expressly denominated in the inflating fiat currency are most vulnerable. The financial future of many average folks is heavily reliant on one of the following:

- Nothing. They are not saving nor investing and are therefore maximally exposed to currency debasement.

- Social security, which is the world’s largest ponzi scheme and very well may not exist for more than a decade or two. If it does hold up, it will be paid out in debasing fiat currency.

- Other defined benefit plans such as pensions or annuities. Once again, the payouts of these assets are defined in fiat terms. Additionally, they often have large amounts of fixed income exposure (bonds) with yields denominated in fiat currency.

- Retirement portfolios or brokerage accounts with a risk profile that has worked for the last forty years but is unlikely to work for the next forty. These fund allocations often include escalating exposure to bonds for “safety” as investors age (risk parity). Unfortunately, this attempt at risk mitigation makes these folks increasingly reliant on dollar-denominated fixed income securities and, therefore, debasement risk. Most of these individuals will not be nimble enough to pivot in time to retain buying power.

The lesson here is that the everyday worker and investor is in desperate need of a useful and accessible tool that excludes the error term in the fiat debt equation. I am here to argue that nothing serves this purpose more marvelously than bitcoin. Although much remains unknown about this protocol’s pseudonymous founder, Satoshi Nakamoto, his motivation for unleashing this tool was no mystery. In the genesis block, the first Bitcoin block ever mined on January 3, 2009, Satoshi highlighted his disdain for centralized monetary manipulation and control by embedding a recent London Times cover story:

“The Times 03/Jan/2009 Chancellor on brink of second bailout for banks.”

The motivations behind Bitcoin’s creation were certainly multifaceted, but it seems evident that one of, if not the, primary problem Satoshi set out to solve was that of unchangeable monetary policy. As I write this today, some thirteen years since the release of this first block, this goal has been unceasingly achieved. Bitcoin stands alone as the first-ever manifestation of enduring digital scarcity and monetary immutability — a protocol enforcing a dependable supply schedule by way of a decentralized mint, powered by harnessing real world energy via Bitcoin mining and verified by a globally-distributed, radically-decentralized network of nodes. Roughly 19 million BTC exist today and no more than 21 million will ever exist. Bitcoin is conclusive monetary reliability — the antithesis of, and alternative to debasing fiat currency. Nothing like it has ever existed and I believe its emergence is timely for much of humanity.

Bitcoin is a profound gift to the world’s financially marginalized. With a small amount of knowledge and a smartphone, members of the middle and lower class, as well as those in the developing world and the billions who remain unbanked, now have a reliable placeholder for their hard earned capital. Greg Foss often describes bitcoin as “portfolio insurance,” or as I’ll call it here, hard work insurance. Buying bitcoin is a working man’s exit from a fiat monetary network that guarantees depletion of his capital into one that mathematically and cryptographically assures his supply stake. It’s the hardest money mankind has ever seen, competing with some of the softest monies in human history. I encourage readers to heed the words of Saifedean Ammous from his seminal book “The Bitcoin Standard:”

“History shows it is not possible to insulate yourself from the consequences of others holding money that is harder than yours.”

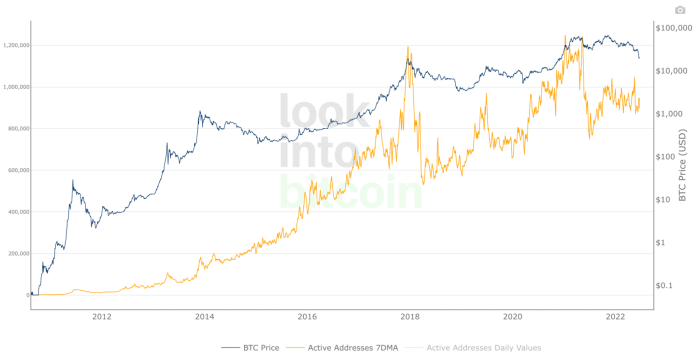

On a zoomed out timeframe, Bitcoin is built to preserve buying power. However, those who choose to participate earlier in its adoption curve serve to the benefit the most. Few understand the implications of what transpires when exponentially growing network effects meet a monetary protocol with absolute supply inelasticity (hint: it might continue to look something like the chart below).

(Chart/LookIntoBitcoin.com)

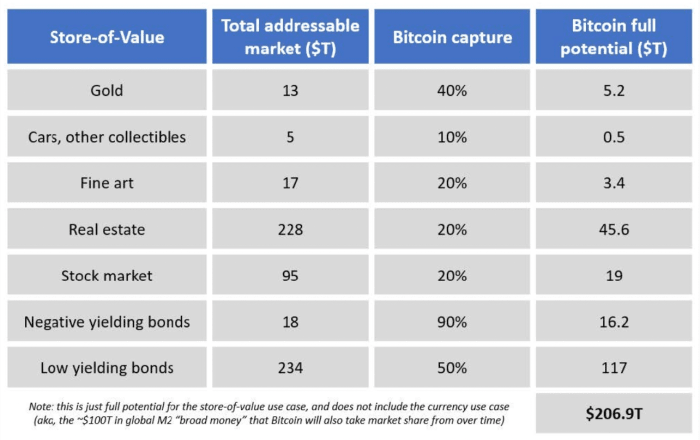

Bitcoin has the makings of an innovation whose time has come. The apparent impenetrability of its monetary architecture contrasted with today’s economic plumbing in tremendous disrepair indicates that incentives are aligned for the fuse to meet the dynamite. Bitcoin is arguably the soundest monetary technology ever discovered and its advent aligns with the end of a long-term debt cycle when hard assets will plausibly be in highest demand. It’s poised to catch much of the air escaping the balloons of a number of overly monetized4 asset classes, including low- to negative-yielding debt, real estate, gold, art and collectibles, offshore banking and equity.

(Chart/@Croesus_BTC)

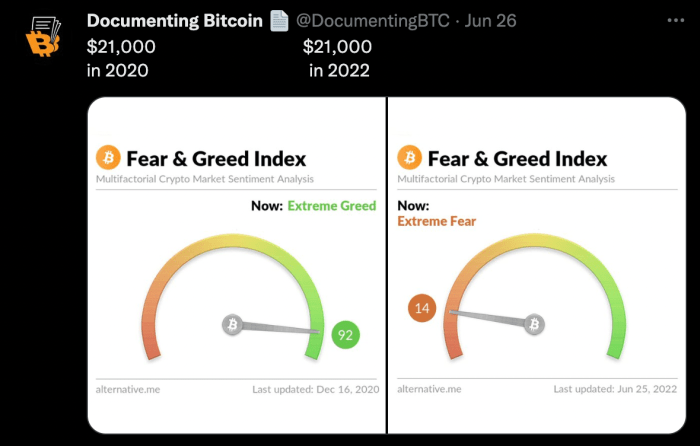

It’s here where I can sympathize with the eye rolls or chuckles from the portion of the readership who point out that, in our current environment (July 2022), the price of Bitcoin has plummeted amidst high CPI prints (high inflation). But I suggest we be careful and zoom out. Today’s capitulation was pure euphoria a little over two years ago. Bitcoin has been declared “dead” over and over again through the years, only for this possum to re-emerge larger and healthier. In fairly short order, a similar BTC price point can represent both extreme greed and subsequently extreme fear on its road to escalating value capture.

(Tweet/@DocumentingBTC)

History shows us that technologies with strong network effects and profound utility — a category I believe Bitcoin fits in — have a way of gaining enormous adoption right underneath humanity’s nose without most fully recognizing it.

(Photo/Regia Marinho)

The following excerpt from Vijay Boyapati’s well known “Bullish Case for Bitcoin” essay5 explains this well, particularly in relation to monetary technologies:

“When the purchasing power of a monetary good increases with increasing adoption, market expectations of what constitutes “cheap” and “expensive” shift accordingly. Similarly, when the price of a monetary good crashes, expectations can switch to a general belief that prior prices were “irrational” or overly inflated. . . . The truth is that the notions of “cheap” and “expensive” are essentially meaningless in reference to monetary goods. The price of a monetary good is not a reflection of its cash flow or how useful it is but, rather, is a measure of how widely adopted it has become for the various roles of money.”

If Bitcoin does one day accrue enormous value the way I’ve suggested it might, its upward trajectory will be anything but smooth. First consider that the economy as a whole is likely to be increasingly unstable moving forward — systemically fragile markets underpinned by credit have a propensity to be volatile to the downside in the long run against hard assets. Promises built on promises can quickly fall like dominoes, and in the last few decades we’ve experienced increasingly regular and significant deflationary episodes (often followed by stunning recoveries assisted by fiscal and monetary intervention). Amidst an overall backdrop of inflation, there will be fits of dollar strengthening — we are experiencing one currently. Now add in the fact that, at this stage, bitcoin is nascent; it’s poorly understood; its supply is completely unresponsive (inelastic); and, in the minds of most big financial players, it’s optional and speculative.

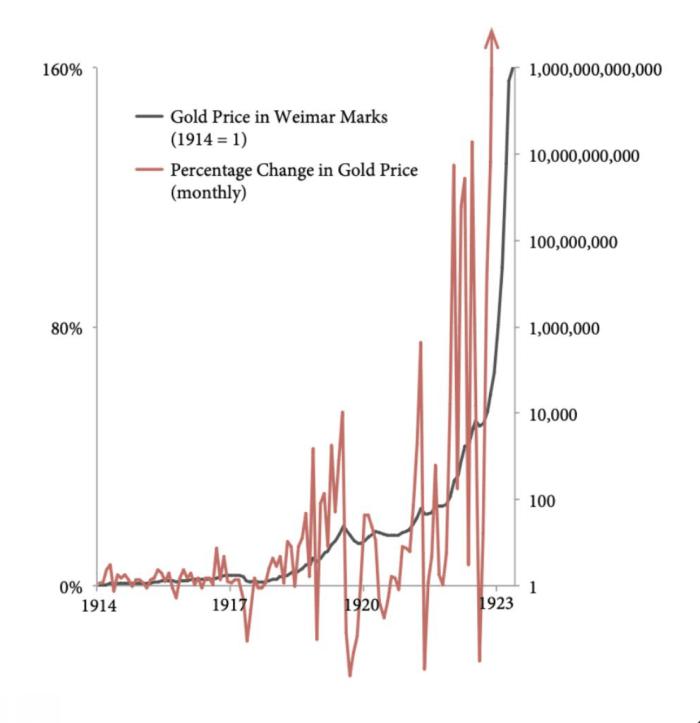

As I write this, Bitcoin is nearly 70% down from an all-time high of $69,000, and in all likelihood, it will be extremely volatile for some time. However, the key distinction is that BTC has been, and in my view will continue to be, volatile to the upside in relation to soft assets (those with a subjective and expanding supply schedules; i.e. fiat). When talking about forms of money, the words “sound” and “stable” are far from synonymous. I can’t think of a better example of this dynamic at work than gold versus the German papiermark during the hyperinflation in the Weimar Republic. Soak in the chart below to see how tremendously volatile gold was during this period.

(Chart/Daniel Oliver Jr.)

Dylan LeClair has said the following in relation to the chart above:

“You’ll often see charts from Weimar Germany of gold priced in the paper mark going parabolic. What that chart doesn’t show is the sharp drawdowns & volatility that occurred during the hyper-inflationary period. Speculating using leverage got wiped out multiple times.”

Despite the papiermark inflating completely away in relation to gold over the long run, there were periods where the mark significantly outpaced gold. My base case is that bitcoin will continue to do something akin to this in relation to the world’s contemporary basket of fiat currencies.

Ultimately, the proposition of bitcoin bulls is that the addressable market of this asset is mind numbing. Staking a claim on even a small portion of this network may allow members of the middle and lower classes to power on the sump pump and keep the basement dry. My plan is to accumulate BTC, batten down the hatches and hold on tight with low time preference. I’ll close this part with the words of Dr. Jeff Ross, former interventional radiologist turned hedge fund manager:

“Checking and savings accounts are where your money goes to die; bonds are return-free risk. We have a chance now to exchange our dollar for the greatest sound money, the greatest savings technology, that has ever existed.”6

In Part 3, we’ll explore two more key ways in which bitcoin works to rectify existing economic imbalances.

Footnotes

1. Although this is often labeled as “money printing,” the actual mechanics behind money creation are complex. If you would like a brief explanation of how this occurs, Ryan Deedy, CFA (an editor of this piece) explained the mechanics succinctly in a correspondence we had: “The Fed is not allowed to buy USTs directly from the government, which is why they have to go through commercial banks/investment banks to carry out the transaction. […] To execute this, the Fed creates reserves (a liability for the Fed, and an asset for commercial banks). The commercial bank then uses those new reserves to buy the USTs from the government. Once purchased, the Treasury’s General Account (TGA) at the Fed increases by the associated amount, and the USTs are transferred to the Fed, which will appear on its balance sheet as an asset.”

2. From “Does the National Debt Matter” by Lyn Alden

3. From “Why Every Fixed Income Investor Needs to Consider Bitcoin as Portfolio Insurance” by Greg Foss

4. When I say “overly monetized,” I’m referring to capital flowing into investments that might otherwise be saved in a store of value or other form of money if a more adequate and accessible solution existed for retaining buying power.

5. Now a book by the same title.

6. Said during a macroeconomics panel at Bitcoin 2022 Conference

This is a guest post by Dan. Opinions expressed are entirely their own and do not necessarily reflect those of BTC Inc or Bitcoin Magazine.

[ad_2]

Source link