[ad_1]

At this point in COVID, I don’t want to think about how many at-home test kits my family has burned through (or what that privilege has cost my bank account). And even still, my children have had to sit in pharmacy drive-throughs, with mom and dad swabbing and mixing samples in the front seat, for school-certified PCR testing whenever they get a runny nose.

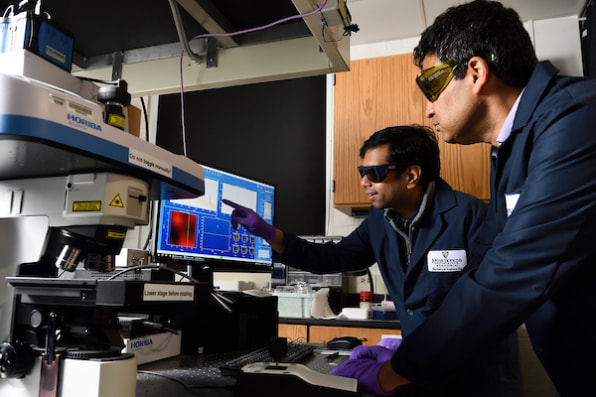

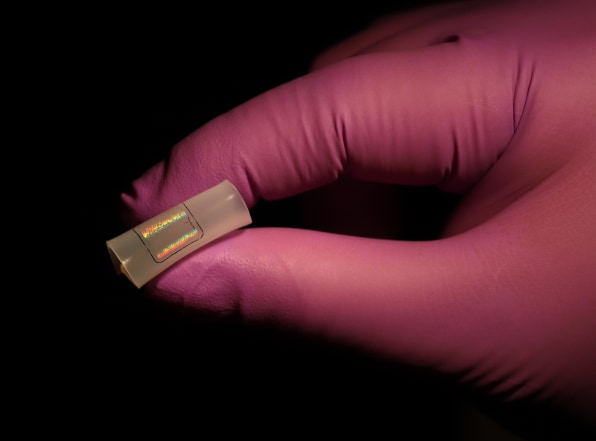

We must be able to come up with something better than this, and, as it turns out, researchers at Johns Hopkins University have. A team at the university’s Whiting School of Engineering, led by associate professor Ishan Barman, has developed a COVID sensor that’s smaller than a postage stamp. Literally, all you have to do is spit on it (or, more likely, swab your mouth), and in 10 minutes, it can be scanned much like a barcode to tell if you have COVID with the same accuracy as a PCR test. (It can also test for all sorts of other viral infections like H1N1 and Zika.) Using this type of sensor, researchers believe that we can remove the onus of testing at home or in a pharmacy, and instead, test for COVID right on the spot in large public spaces.

“The first thing we’re thinking of is testing at airports and stadiums,” says Barman. “We think these sensors could be read with handheld . . . readers, like infrared gun thermometers used today.” Much like an arena employee scans your ticket with a handheld barcode reader, Barman imagines they would scan your saliva sample before entry.

How does this technology actually work? It breaks down into three components. First you have the scanner (a handheld device that existed before this new research). It’s technically a Raman spectrometer, which fires lasers at viruses. The exact way these laser photons bounce off of the microbes provides a sort of viral thumbprint. Next is the new sensor material, which is a metal antenna that uses nanotechnology to boost the laser’s effectiveness in analyzing the sample. It’s an amplifier, essentially, that enhances spectrometer’s vision by a massive eight orders of magnitude, allowing it to see even trace amounts of virus in a sample. Finally, the team constructed an AI model, which is what allows them to actually translate these photon patterns into legible viral thumbprints.

In practice, you would swab or spit on the sensor—technically, the system needs just a drop (and the UX around getting that drop onto the sensor will require some development)—wait 10 minutes, and an employee would scan it with the Raman spectrometer to see if you were positive for SARS-CoV-2 or any other virus. Because of how the system is built, the AI can constantly learn how to identify more viruses. So, while tested on the aforementioned COVID-19, H1N1, and Zika, the sensor, with enough development, can theoretically spot any virus that’s present in your saliva—and it can spot these various infections all at once. What that could mean for living with COVID-19 as an endemic is promising for public health. Rather than relying upon vaccination passports or PCR tests that might be days out of date by the time results arrive, Barman believes that any large gathering space could use his lab’s sensor technology as a real-time screening tool.

Is there a catch? Well, the prospect of 30,000 people spitting outside a stadium is a bit gross to consider! Beyond that, producing enough sensors might be expensive or difficult practically. Technically speaking, these sensors are reusable. But because of their extreme sensitivity to ambient viruses, Barman imagines consumers treating them as disposable, rather than sterilizing them for reuse. (Then again, we heard the same argument about N95 masks before there were shortages, which proved reuse was completely possible with a bit more effort.)

The device as detailed in the most recent paper costs about $20 to produce, but Barman says it would cost about half to a third of that at scale. Meanwhile, the lab is also working on a yet-to-be-published modification to the sensor material, which would drive pricing down to just $1 per test—which is what you’d need to be feasible for mass use in public spaces. Barman’s team has patented this technology and hopes to get FDA approval within six months before bringing it to market within about a year.

“If you think about airports and so on, it’s not that difficult [to integrate our technology] because, even today, they can swab your hands, testing for residue of gunpowder and drugs,” says Barman. “For those applications, there’s no problem. It can fit right in.”

[ad_2]

Source link