[ad_1]

Receive free UK inflation updates

We’ll send you a myFT Daily Digest email rounding up the latest UK inflation news every morning.

The Bank of England’s efforts to tame inflation are set to hit a bump in the road this month with official figures expected to show prices rising more rapidly again in August.

The annual rate of consumer price inflation dipped in July to 6.8 per cent, from 7.9 per cent in June, but the rising cost of petrol and diesel is the main factor likely to increase it to 7.1 per cent in August, according to a BoE forecast. The August data will be published on September 20.

The expected jump in headline consumer price inflation will complicate moves by senior BoE officials to give themselves the option of pausing interest rate rises when the central bank’s Monetary Policy Committee meets on September 21.

Andrew Bailey, BoE governor, last week cast doubt on the need to tighten monetary policy further to tackle inflation — by saying rates were now “much nearer” their peak than before.

There are many reasons why the August inflation data from the Office for National Statistics is likely to be relatively bad news, according to economists.

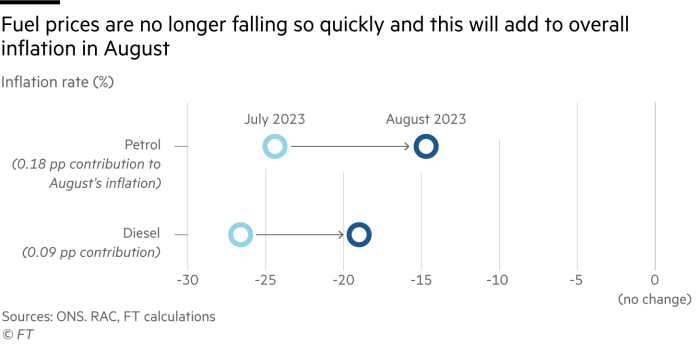

In August 2022, fuel prices fell more than 6 per cent compared with the previous month, while this July they rose more than 4 per cent month on month, according to the latest data from the RAC motoring organisation.

Even though fuel prices in August were about 15 per cent lower than one year earlier, the annual rate of decline was much smaller than in July.

So petrol and diesel prices are set to pull the headline inflation rate for August down less compared to July.

In total, the changes in petrol prices are expected to contribute almost 0.2 percentage points to inflation in August. The changes in diesel prices are likely to add almost 0.1 percentage points.

Meanwhile, new alcohol duties that took effect at the start of August raised the prices of wine, spirits and some beer.

The duty on a bottle of average strength wine rose 44p. If added to a £7 bottle of wine, this would raise the price by 6.3 per cent compared with August last year, when there was no duty increase.

The prices of food and other goods are rising more slowly than last year and so are likely to partly offset the fuel and alcohol duty effects.

But there are other factors driving price rises. The annual rate of services inflation increased from 7.2 per cent in June to 7.4 per cent in July, the highest level since March 1992. The annual rate of core inflation, which excludes volatile food and energy prices, was unchanged at 6.9 per cent in July.

Bailey told MPs last week he was expecting a difficult set of inflation data for August.

“I should say that it is possible that we will get a tick up [in inflation] in the next release [by the ONS], because fuel prices went down in August last year and up a bit in August this year, but I do not see that as essentially changing the path,” he said.

Jeremy Hunt, the chancellor, has also been preparing the ground for an increase in inflation, telling the BBC last week: “I do think we may see a blip in inflation in [the] September [publication] but after that, the Bank of England is saying it will fall down to around 5 per cent.”

Both the BoE and the Treasury expect the growth in consumer prices to dip below 5.3 per cent by the fourth quarter of the year partly because of falling household energy bills, enabling Rishi Sunak to meet his commitment to halve inflation by the end of the year. Inflation stood at 10.7 per cent in the fourth quarter of 2022.

But this achievement will be a difficult message to sell to the public because of a widespread misunderstanding of the phrase “falling inflation”, according to Johnny Runge, senior research fellow at King’s College London.

Surveys that he has presented to government officials show that between 30 and 40 per cent of the public, when asked, think that lower inflation means that prices have fallen.

Runge said the public was likely to treat government delight at achieving the prime minister’s inflation pledge with some irritation.

“Many will not believe that inflation has fallen or the government pledge has been achieved, because they will not feel prices have fallen — because they haven’t,” he added.

Apart from a sceptical public, the other difficulty that Bailey and Hunt are likely to face is that underlying measures of inflation have not definitively turned down yet.

In the July data, roughly two-thirds of the categories of prices of goods and services measured by the ONS were rising at an annual rate of more than 5 per cent, a figure hardly different from a year earlier. This demonstrates the broad nature of the UK’s inflation problem.

Another way of determining whether inflationary pressures are diminishing, favoured in the US, is to look at more recent seasonally-adjusted price changes for goods and services and compare these with the annual rate.

With UK gas and electricity prices falling, this data shows that near-term measures of inflation, such as the annualised three month rate, is back to the BoE’s 2 per cent target.

The six month, three month and one month annualised rates of headline inflation are well below the 12 month rate, indicating that price rises are moderating.

But the same benign view does not apply to price rises in services and core inflation.

Paula Bejarano Carbo, associate economist at the National Institute of Economic and Social Research, a think-tank, said: “We have yet to see a turning point in the underlying rate of inflation.”

[ad_2]

Source link