[ad_1]

Publishing a book is often a cathartic experience for writers. It allows them to share their deepest and most heartfelt thoughts with the world. It’s a chance to prove their critics wrong and create something meaningful too. Whether it becomes a bestseller or simply gathers dust on the shelf, it’s a lifetime achievement for many.

However, for some writers, that initial euphoria can sour. Writers who think more about their past works come to hold a profound dislike, denial, or even outright concealment of their own literary creations. In this list, we’ll give you ten examples of authors who despised their own works years after they were released. These writers shamelessly disavowed and even moved to conceal their own works.

Related: Top 10 World Famous Books That Got Rejected

10 Dante Gabriel Rossetti

Dante Gabriel Rossetti led a life filled with passion and turmoil through the 19th century. His relatives were renowned writers, and his wife, Elizabeth Siddal, was a prominent artist’s model. Along with his creative pursuits, Rossetti also engaged in numerous affairs with women.

That happened, much to Elizabeth’s heartbreaking dismay. Her depression escalated because of it. Eventually, it led to her intentional overdose of laudanum. In a bizarre and somewhat romantic gesture, Rossetti placed a notebook filled with his poems into Elizabeth’s hair before she was buried.

At that point, Rossetti’s story took an unexpected turn. Years later, he had his wife’s grave unearthed to retrieve the notebook for inspiration. Unfortunately, the passage of time had taken its toll. Worms had devoured parts of the pages. Despite this setback, the poems were eventually published. Sadly, though, they didn’t receive much critical acclaim. Rossetti was plagued by guilt for both the death and the desecration of the grave. From there, he carried the weight of violating his wife’s resting place for the remainder of his life. And the book of poems became the most shameful output of his long career. [1]

9 Franz Kafka

If you thought reading The Metamorphosis in high school was bad, think again. Its author Franz Kafka was his own worst critic. In fact, he burned a staggering ninety percent of his writings. And just when you thought it couldn’t get worse, on his deathbed, Kafka asked his friend Max Brod to destroy the rest. But thankfully, Brod had other plans. He went against Kafka’s wishes and published his friend’s books. He even risked his life by smuggling a briefcase filled with Kafka’s papers across the border from Germany before the Nazis sealed it shut.

But wait! There’s more! The remaining writings and sketches found their way to Brod’s secretary. Then, they eventually ended up in the possession of her daughters. Now, they’re caught up in a legal battle with the Nation of Israel over the ownership of these century-old papers that were supposed to be destroyed in the first place.

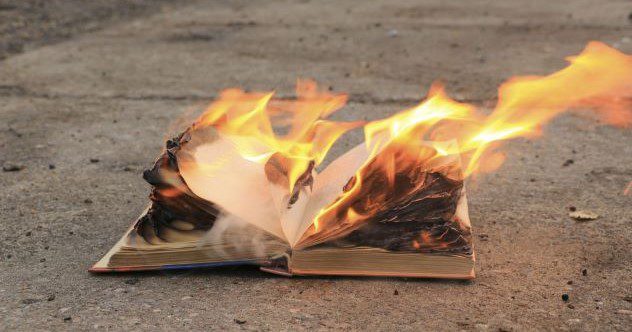

Meanwhile, Kafka’s lover managed to keep 20 of his notebooks safe for a while. Sadly, they were confiscated by the Gestapo in 1933. A volunteer project is underway, scouring World War II documents in the hopes of locating these lost notebooks. But they may never be found. It just goes to show that if you truly want your work annihilated, you might as well toss it into the flames yourself. That’s quite the renunciation![2]

8 Don DeLillo

Don DeLillo is a renowned figure in the Postmodern literature movement. He has gained recognition as an esteemed author and playwright through that. One notable critic, Harold Bloom, even considers DeLillo as one of the four living American novelists deserving of praise. However, the book that may capture your interest the most is noticeably absent from DeLillo’s official published works.

The hidden gem is titled Amazons. It was co-authored by DeLillo back in 1980. After a series of six novels that received critical acclaim but failed to make a financial impact, DeLillo took a lighthearted detour with this book. Amazons presents a humorous mock autobiography. It follows the escapades of Cleo Birdwell, the NHL’s first female hockey player. As told in the faux-bio, her journey mainly involves intimate relationships with coaches and teammates. So it’s not exactly high-brow stuff.

Despite its apparent humor, DeLillo has never publicly acknowledged his involvement in writing Amazons. In fact, he specifically requested to exclude it from his official bibliography. It’s a missed opportunity, maybe. If more acclaimed geniuses took breaks from their serious works to create something amusing and relatable, perhaps the rest of their creations would receive greater attention from readers. Or maybe they’ll just turn out like DeLillo—and be adamant about keeping it off the radar.[3]

7 William Powell

Are you familiar with the controversial book from 1970 called The Anarchist Cookbook? It’s a guide that covers everything from making explosives to hiding drugs. Despite its inaccurate and dangerous explosives recipes, the book still maintains a strong following. Now, that has come much to the dismay of its author, William Powell.

Powell wrote the book when he was just 19 years old and filled with anger over the Vietnam War draft. He wanted to rebel against the system. But now, as a father and a teacher, he deeply regrets his creation. In recent reviews and requests, he has pleaded with people not to buy the book. He now realizes that he no longer agrees with its central idea that violence is an acceptable means for political change.

Unfortunately, Powell doesn’t own the rights to the book anymore. So all he can do is give interviews and try to raise awareness about something he desperately wants to be forgotten. For him, it remains a dark stain on his legacy as a writer and an author. And for the world, The Anarchist Cookbook, unfortunately, continues to be a dismaying and deeply regrettable work.[4]

6 Stephen King

Stephen King often faces mockery for his extensive body of work. Some of his more eccentric ideas—like killer trucks—are certainly out there. Yet it’s important not to overlook the genuinely terrifying nature of many of his early books. One that proved tragically prophetic is best emblematic of this. King’s debut novel Rage revolves around a high school student who brings a gun to school, kills two teachers, and holds his classmates hostage. Disturbingly, the captives start sympathizing with him in a Tyler Durden-esque way.

The rationale behind censoring the book is sadly clear. In light of the alarming surge in school shootings, King and his publishers decided against potentially inspiring anyone. They didn’t want to promote a novel narrated from a school killer’s perspective. Shockingly, at least one real-life shooter had a copy of Rage in their locker. Quickly, that prompted King and his publishers not to release any future editions.

King wrote the story during his college years under the pen name of Richard Bachman. Thus, he can consider himself fortunate to have escaped scrutiny from school administrators as a potential risk. Still, the disturbing novel remains a dark spot in King’s career—as far as the man himself is concerned.[5]

5 Mark Twain

Mark Twain was a man famously known for his irreverence. But he had a buried secret in his writings. Surprisingly, it wasn’t scandalous, dark, or shameful. No, it was something much simpler: a collection of fart and sex jokes. Titled 1601 and subtitled Conversation, as it was by the Social Fireside, in the Time of the Tudors, Twain crafted this piece as a playful parody. He wanted to lampoon the idea that the Elizabethan era was all about strict propriety. It imagines a fictional gathering with Queen Elizabeth, other noblewomen, Shakespeare, and Sir Walter Raleigh. There, the group engages in a humorous fireside chat.

So why did Twain keep this work anonymous for 26 years before admitting authorship? After all, at one point, he was actually proud of 1601. In a letter to a friend, he admitted it was “dreadfully funny” and one of the rare pieces that made him laugh. However, later on, he claimed that if there was anything decent about it, it was merely an oversight on his part. Perhaps Twain didn’t want this lighthearted and relatively minor story to overshadow his more significant works like Tom Sawyer and Huckleberry Finn.

It turned out to be a wise move, as mainstream publishers considered 1601 unfit for print from 1880 until the early 1960s. At that point, society became more accepting of Elizabethans cracking jokes about pubic hair, and it became a bit of a legendary read in its own right.[6]

4 Martin Amis

Renowned British author Martin Amis has a lesser-known work that he prefers to keep under wraps. Titled Invasion of the Space Invaders, this guide delves into the world of early video games. But it’s not exactly what you might be thinking. It’s true that the book has an introduction by Steven Spielberg. And it’s filled with witty remarks like “Bag it” when it comes to gobbling up fruit symbols.

But Amis seems reluctant to acknowledge his involvement in this publication. In fact, a reporter once jokingly praised it as one of his best works, but the expression on Amis’s face revealed a mix of pity and contempt. Clearly, it is something he’d rather not discuss.

While Martin Amis is recognized for his serious literary endeavors and engaging in heated debates about radical Islamism, his venture into the realm of video games remains an enigmatic chapter in his career. It’s a departure from what he often writes about. And it’s a unique book by any standard. Clearly, though, it’s one he would prefer to ignore.

Nevertheless, Invasion of the Space Invaders continues to captivate readers with its insights into early gaming. Plus, its clever advice—like reminding PacMan players to stay humble and not succumb to macho tendencies on the dotted screen—is truly timeless. But despite its merits, Amis maintains a reluctance to discuss or take credit for this peculiar work. Thus, he has left the reasons behind its authorship shrouded in mystery and curiosity.[7]

3 Nikolai Gogol

Nikolai Gogol, a once-renowned Russian author, has a name that now evokes images of mobsters or video game bosses. However, 150 years ago, he was a highly influential writer. He inspired the likes of Nabokov and Dostoyevsky. Among his notable works, Dead Souls stood out as a modern reimagining of Dante’s Divine Comedy. Gogol viewed it as a mere prelude to a grand epic poem he envisioned. That poem was supposed to bring about social change and save Russia from its own troubles.

But something went terribly wrong. Gogol fell under the influence of a fervent priest named Matvey Konstantinovsky while working on the sequel. This zealous figure convinced Gogol that his creative endeavors were an affront to God. Consequently, on the fateful night of February 24, 1852, Gogol destroyed the almost finished manuscript of Dead Souls II.

All the notes he had for the third installment were gone too. Only a few fragments survived the flames. Consumed by remorse, he immediately ceased eating and passed away nine days later. With that went Gogol’s career, legacy, and whatever future writings he could have conjured.[8]

2 Ian Fleming

In the early 1960s, Ian Fleming enjoyed immense success as the author of the James Bond novels. However, he grew concerned when he discovered his adult thrillers were gaining popularity among schoolchildren who idolized the famous spy for some of the wrong reasons. To address this issue, Fleming decided to write a cautionary tale. In it, he depicted Bond’s world from an alternate POV. The outcome was The Spy Who Loved Me. The book follows the experiences of a woman named Vivienne Michel.

Vivienne’s narrative included events such as losing her virginity in a movie theater, working as a secretary, undergoing an abortion, and managing a struggling motel. Her life takes a dangerous turn when mobsters attempt to set the motel on fire for insurance money. Only in the final third of the book does Bond make an appearance. In it, he eliminates the thugs, seduces Vivienne, and departs before the story ends.

Unfortunately, Fleming’s intentions fell short. Critics heavily criticized the novel. They dismissed it despite its attempt at progressive dialogue. Fleming himself was disappointed and considered the experiment a failure. So he refused to authorize any paperback or hardcover reprints. In subsequent novels, he ignored the events of The Spy Who Loved Me. Then, he allowed the book’s title to be used for a movie only if its plot had no connection to the novel. Even so, the book did introduce one memorable character to the Bond canon: Horror, a gangster with metal teeth who inspired the iconic film henchman Jaws.[9]

1 Hergé

When it comes to controversial Tintin books, Tintin in the Congo takes the spotlight. In this story, the infamous Belgian reporter offers up a hearty dose of racism and big game hunting down in the wilds of Africa. But writer/artist Hergé didn’t hesitate to reissue it alongside his newer works even in his later years. In fact, there was just one missing book in that collection, and it wasn’t about the Congo. Instead, Tintin in the Land of the Soviets has all but disappeared. That marked the Belgian’s very first Tintin adventure and also his most controversial.

Why did Hergé refuse to redraw it? Well, the first few Tintin stories were actually imposed on Hergé by his editor. The man was an ultraconservative priest with a mission to teach kids about the dangers of communism. But here’s the catch: The priest made up most of the details. Hergé relied on one sensationalistic book criticizing the communist regime to create the story. Looking back, Hergé admitted it was a youthful mistake. Ironically, historians found some accuracy in his depictions of the harsh living conditions in Russia at the time, but it wasn’t enough to get the book back.

For years, Tintin in the Land of the Soviets remained hidden from the shelves. Hergé eventually relented when bootleg copies flooded the market. But even when they did, he insisted that only the original black and white strip be reprinted without updates or colorization. Come to think of it, we can’t help but wonder if some Tintin fanboy is working on that as we speak. Just don’t count on Hergé ever supporting that old Soviet schlock.[10]

[ad_2]

Source link