[ad_1]

At a summit in Tianjin this week, the Chinese premier Li Qiang took the opportunity to make the foreign executives in attendance feel welcome.

Li, seen as the most business friendly member of President Xi Jinping’s inner circle, wrapped up a talk at the World Economic Forum’s New Champions meeting with a play on words in Chinese — mixing the word “laowai”, which means foreigner, with the term “laoxiang”, which means “townspeople”.

“I hope you can become our townspeople,” he told a business round table.

Li’s charm offensive at the meeting — nicknamed the “Summer Davos,” in reference to the far larger WEF event held in Switzerland in January — was intended to make attendees from overseas abandon all thoughts of “decoupling” and “de-risking”.

But here and elsewhere it is hard to escape the geopolitical tensions between his country and the US-led west, which many in China fear are peaking at a critical juncture for its economy.

After the country’s zero-Covid restrictions ended last year, the economy had a robust recovery in the first quarter. But this has slowed in recent months, with the government reporting on Friday that manufacturing activity fell for the third straight month while services were at their weakest in six months.

Beijing blames part of the geopolitical tensions on Washington after it imposed controls on high-technology exports to China and shot down a suspected Chinese spy balloon early this year.

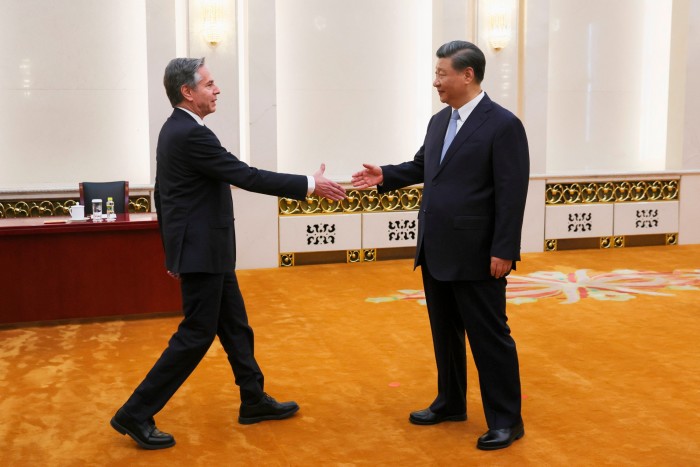

There are signs that the US and China are trying to improve relations. When President Xi Jinping met US secretary of state Antony Blinken in Beijing last week, the two sides said there was “progress” towards stabilising ties — though it was quickly undone just a day later when US President Joe Biden called Xi a “dictator” at a private fundraising event.

China has also been making overtures to US business leaders as its economic recovery stalls. Jamie Dimon, chief executive of JPMorgan, was wooed by senior officials in Shanghai in late May, and Tesla’s Elon Musk was invited to meet government ministers in Beijing the same week. Apple’s Tim Cook and GM’s Mary Barra also visited China this spring, while Microsoft co-founder Bill Gates met with Xi himself in June.

But foreign investors have been unnerved at Beijing stepping up security measures. This week, just two days after Li’s comments at the WEF meeting, the government passed a new foreign relations law that strengthens the legal basis for “countermeasures” against western threats to national and economic security. This follows crackdowns on foreign consultancies and expanded espionage and data security laws.

With the economic recovery weakening, however, many wonder if Beijing will soon be forced to choose whether to prioritise the economy over security — or whether China is entering a new phase in which the government will tolerate relatively low growth, while clamping down further to strengthen resilience to external threats.

Inside China, anxiety is running deep. “This is the first time in 40 years that the Chinese public are not sure if things are going to get better,” says one Chinese commentator on the economy, who did not want to be named.

Among the townspeople

The sharp changes in China over the past three years were on display at the WEF this week.

Some of these were technological, from the prevalence of electric vehicles on Tianjin’s streets to the conversion of China to a near cash-free society. Anyone without an indigenous payments app such as WeChat or Alibaba could not wander far from the venue. Many complained that even foreign credit cards did not work.

Others hinted at the more visible presence of the Chinese Communist party. A bookstand at the venue’s entrance was stacked with titles such as the multi-volume Xi Jinping, The Governance of China and Why the Communist Party of China is Confident.

A deeper change, however, was the paucity of global CEOs at the forum, say some who had been to previous WEFs in China, and the constrained nature of some of the debate. Set up at short notice after the end of zero-Covid, it was harder for bosses to incorporate the forum into their schedule, organisers say.

But others blame geopolitics, which is forcing many US CEOs in particular to keep a low profile. Those who attended JPMorgan’s Shanghai summit in May did so behind closed doors.

Among the range of attendees in Tianjin, some welcomed the chance to see China for themselves after years of hearing about the “China threat” in the US.

“This is my first time in China. I thought I should be a little bit nervous,” says JD LaRock, president of the Network for Teaching Entrepreneurship, a New York-based non-profit organisation.

“I find everybody that I’ve met has been friendly, open, interested in talking about how we can work together. It’s a different perspective from what the US politicians say.”

A German business executive, however, expressed his frustration with how many participants, particularly Chinese executives and academics, seemed to stick closely to the Chinese government’s official narrative.

“They are keen to create the impression that everything is back to normal but it’s not,” says the executive. “It’s such a different meeting because, five years ago, they had all those top-level people from the industries in China, but also from the US and Europe. Everybody was discussing openly.”

Yet some present were content to speak freely. At a business roundtable, Volkswagen China head Ralf Brandstätter pointed to the plethora of competition in the Chinese auto market, with over 100 carmakers, saying it was destructive of capital. He also raised the issue of China’s cross-border data security laws, which carmakers have complained are too vague.

Frank Bournois, dean of China-Europe International Business School (CEIBS), which has campuses in several large Chinese cities, praises the “spirit of entrepreneurship” at the event.

But he says the after-effects of the pandemic are still being felt at his business school, with international students numbering just below 100 of the 1,200 full-time MBA students. Normally it would be up to double this.

“International students are hesitant because of the pandemic and repercussions related to the pandemic,” says Bournois. “Geopolitics [at] the moment doesn’t help us much.”

While the US and Beijing are trying to cool tempers this year ahead of a possible meeting between Biden and Xi later this year, the longer-term trajectory of their great power competition is clear, analysts say, particularly on high technology.

“The US realises this is an important juncture in China’s development,” says Eswar Prasad, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution, a US think-tank. Washington knew that China’s bid to invest more in advanced manufacturing and other areas of high technology meant it needed to also look abroad for foreign investors. “At the moment China needs foreign technology.”

Reigniting the recovery

That helps explain Li’s presence at the Tianjin event, among other outreach initiatives. But the immediate priority for Beijing will be to stabilise the recovery.

The property sector, a growth engine of the economy, is locked in a long slump. After steadying briefly this year, it began to slip again in recent months, threatening consumer confidence. China’s exports and manufacturing sectors are also struggling.

Some believe there is a risk of a “balance sheet recession”, when the indebted focus on paying down debt, as happened in Japan in the 1990s after its bubble burst.

“I think some of the challenges the Chinese are facing are equal to or perhaps more challenging than the Japanese faced 30-something years ago,” says Richard Koo, chief economist at the Nomura Research Institute, who coined the term.

He says the only way to fix a balance sheet recession is a very large fiscal response. The government needs to borrow the money that individuals and corporates are saving and recirculate it in the economy, Koo says, otherwise GDP will contract.

The best path to achieving this might be to complete unfinished apartments left over from the sector’s bust in recent years, Koo adds. While local government finances are strained, the central government is in better shape. “The central government this time will really have to come out and borrow the money,” he says.

One Chinese economist with a Beijing think-tank says large monetary stimulus is needed, as well as fiscal. The government has cut interest rates but only marginally. “I’m very worried about near-term growth prospects,” he says, calling for steps to put a floor under the property market.

Policymakers led by Li Qiang, who took office in March, have yet to announce a comprehensive stimulus plan. The politburo, the party’s top decision-making body, is due to meet in July to discuss economic policy and insiders say any stimulus would likely come after that session.

But few are expecting anything at the scale of the $570bn fiscal rescue package China unleashed in 2008. The Chinese economy is working through important structural changes that will take time, said economist Zhu Min at a WEF panel on the country’s rebound.

The property sector was suffering from long-term oversupply with demand this year 24 per cent less than the industry’s capacity, said the former IMF deputy managing director. Trade is also undergoing structural change as the share of exports going to the US and Europe fell.

But the economy was shifting rapidly towards new industries, Min added, such as electric vehicles and the green economy. “Really, I observe the whole economy structure shifting,” he told the audience. “You will see volatility [but] that’s OK.”

The lingering question is how US-China geopolitical tensions will play into that shift. World Trade Organisation director-general Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala said at the WEF that there was evidence that investment was shifting out of China to other parts of Asia. “If the investment patterns shift, the trade patterns will shift,” she said.

In the near-term, the focus for China will be to try to achieve this year’s growth target of 5 per cent, its lowest in decades. For that, it may need to lower the geopolitical temperature, especially with the US, but also with other trade partners.

Beijing may also wish to reconsider the security state approach, which intensified during Covid, says the Chinese commentator, and which still weighs on the economy and on society. “The whole state-society relationship has changed and people can feel that. And they [the government] need to dial it back.”

[ad_2]

Source link