[ad_1]

In The Bitcoin Rorschach Test, I examined how technology shapes human culture. For most of humanity’s existence, only those with access to industrial-sized resources or political power could create, develop or produce technologies at a sufficient scale to have influence. The invention of the internet and the emergence of the peer-to-peer economy described in this article allows us to break free from these limitations. It opens the floodgates for the vast majority of the world’s population to become producers and creators of the technologies that impact the direction of our civilization without the oversight or influence of a privileged few. The implications of this are tremendous and profound, a world where the nature, function and form of the technologies that shape our lives are born not of states and companies, but of humans cooperating directly with other humans. For this to be a sustainable, meaningful cultural shift, what is needed is a monetary technology congruent with this same spirit.

Since about the mid-19th century, our world has been drifting from an industrial production economy to an information-based economy. In an industrial production economy, value is created primarily by producing material things. To make these at a large scale requires significant amounts of capital to acquire the raw materials for production, the physical infrastructure or machinery to transform them into goods and human labor to orchestrate their production — all of which are unattainable for most of the earth’s population. This leads to a world where the majority are unable to shape or influence the tools and technologies they use in their day-to-day existence in a way that better suits their circumstances or alleviates their problems. Instead, they must choose from the options made available to them based on the preferences of a select few, be that in regards to clothing, construction materials, food, tools and machinery or medicine.

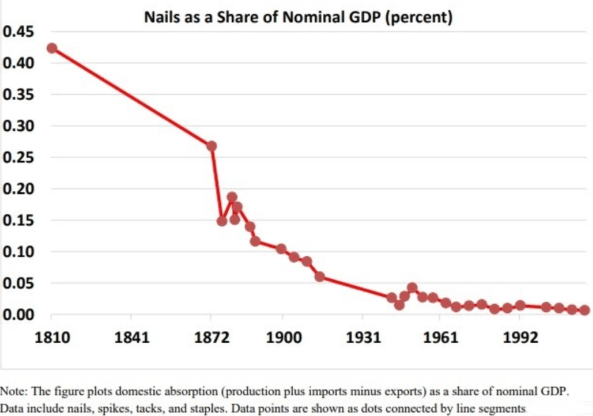

Although the technology of the nail of today is nearly identical to that of 1800, its relevance to the economy has reduced drastically. We used to burn down houses to make it easier to retrieve the nails used in their construction, which seems insane in a world where they can be cheaply and easily obtained from a hardware store. (Source)

For close to 200 years, we have been slowly shifting from this material-based model to one driven by information. This shift is driven by the economic reality that once we have refined the production of physical items to a certain degree, there are diminishing returns to incremental improvements in their manufacturing process. In contrast, the production and distribution of ideas and information yield near limitless possibilities to innovate and create value. Nike, for example, is not a successful company because it drastically innovated in the technology of mass manufacturing shoes, but because it is good at manufacturing symbols. It is the swoosh, the branding of what Nike represents and symbolizes for those that wear them that command the higher prices than what are objectively similar quality shoes available from a budget retailer, or why someone would want to own multiple pairs of what are generally speaking, the same item of clothing. Nike carved out its significant market share by manufacturing symbols, redefining the idea of what a shoe could be and what the connotations of wearing their shoes were, not by significantly improving the quality and capability of sneakers or their manufacturing process.

Of course, this opens up possibilities far beyond improving industries based on physical production. The information economy has allowed the emergence of entire industries that previously never existed. Information and data technology, the mass production and distribution of culture and art such as music and film and many financial services have produced untold value for the world and markets. This was all accomplished by capitalizing on the massive productive potential that can be tapped simply through an increased ability to gather, process and share information, driven into overdrive thanks to the proliferation of the internet.

The capital production economy still very much exists and fulfills a great economic demand. However, the potential for value creation and innovation, and consequently, the direction and shape in which the world’s productive capacity will grow, is driven primarily by information rather than access to industrial manufacturing and raw materials.

With every passing day, economic value becomes concentrated less in atoms and more in bits. What once required physical machinery or labor can now be abstracted into code or data that can instantly be sent over the internet. Many of the barriers that constrained the productive capacity of the majority of the world’s inhabitants stemming from the dominance of the industrial production economy apply less and less with each passing year.

An ever-growing amount of what is required to turn an idea into a good or service no longer requires a large amount of capital, extensive machinery and large amounts of manpower; a personal computer worth several hundred dollars will suffice. And thanks to the mass industrial production of computers and microprocessors, an ever-increasing part of the world’s population can access computational power unfathomable even 30 years ago. The most valuable resources for production are now information and the creativity to repurpose it, something infinitely more accessible in the internet age to the average human being than steel, coal or coordinated mass physical labor. Everyone is now a factory, and ideas are the new oil.

The transition from atoms to bits not only reduces the cost of computing tools able to exponentially leverage every human’s productive capacity, it also opens the doors for a world of willing productive individuals that geography and logistics previously excluded. (Source)

Happening in lockstep with this democratization of the means of production is how the internet exponentially increases our ability to communicate and collaborate on a scale never before imaginable. In the past, the limitations of moving physical items over space made the production of goods and services arduous. Even for goods based on information, the technology did not exist for that information to propagate clearly, rapidly and securely at scale and over massive distances. The internet has largely solved all of these barriers.

This means the pool of available talent has increased massively in scope from what is located within around one or two hours traveling distance from your location to the entire world. Further, these individuals can cooperate and communicate in ways that are essentially only limited by our imaginations — loose ad hoc affiliations with others, in forms that do not require stable, long-term relationships or formal organizational structures. The politics and hindrances on effective cooperation inherent to these hierarchical organizations, the complication of timezones, much of the need for physical proximity, the logistical hurdles to redeploying talent where it is needed within hours or even minutes all no longer prevent us from being optimally able to utilize untouched and unharnessed economic and productive potential. Millions of people can coordinate via software and the internet to make small contributions that, in aggregate, far outweigh the productive capacity of monolithic traditional structures and corporations.

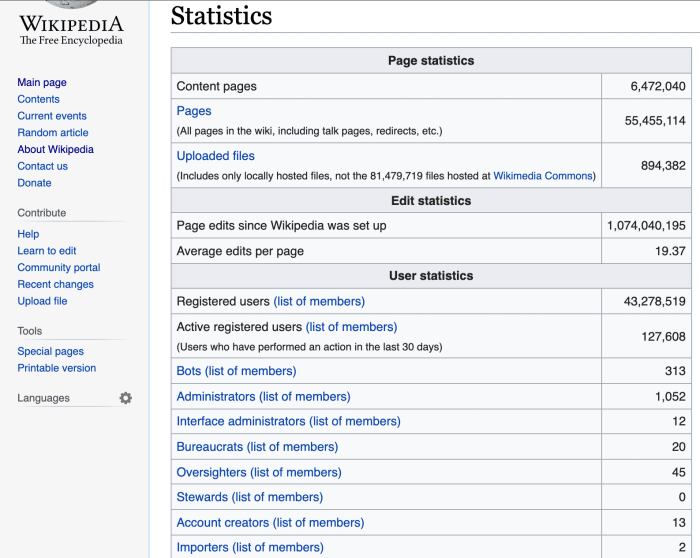

Wikipedia, the largest and most-read reference work in history, is the result of millions of small contributions by millions of people. It would not have been possible without the internet expanding the scope of how and with whom we may cooperate. (Source)

However, the real revolution is not the transition to an information-based economy or a decrease in the cost to produce or collaborate. The same large businesses can also capitalize on these changes in production, produce information products and dominate the market based on capital and their size, as has happened in the industrial production model. Instead, the revolution is the change of the culture and range of economic expression that is unlocked from this democratization of the ability to produce.

In the past, the cost of entry, communication and production itself meant that to produce at scale necessitated, first and foremost, the ability to turn a profit. Without a reliable and consistent revenue stream that exceeded the cost of production, keeping the wheels of a large-scale productive enterprise in motion was not possible. No matter the brilliance of the idea, its importance to a person’s values, or the depth of need for the benefits it bestowed, if that person could not organize its production into the continual generation of profit, then production could not occur.

Consequently, the ability to generate financial return trumped all other considerations, and its influence colored the conversation of whether something is worth doing and what that should look like. The social and economic changes discussed have led to the emergence of a collaborative economy. Peer-to-peer production from human beings enabled them to solve their problems without needing to translate them into formats palatable to large companies or express it in terms of profit, loss and the commercial marketplace. Now, amongst the millions of deeply interconnected human beings that populate the planet, if someone wishes to create something within the ever-growing realms of what is possible with a computer and their imagination, they can do so without gatekeepers or permission.

Type 1 diabetes is a chronic condition in which the pancreas creates little to no insulin. Living with this condition means diligently monitoring your carbohydrate intake at a per-gram precision to precisely calculate and balance insulin levels — 24 hours a day, seven days a week. A glucose monitor alarm going off in the middle of the night means pulling yourself out of bed, calculating insulin requirements and administering an insulin injection or eating something. The average Type 1 diabetic needs to make approximately 300 decisions per day to avoid sickness and maintain health. Over the last 20 years, two separate hardware components evolved to treat the condition, the insulin pump to dispense insulin and the continuous glucose monitor to track sugar levels. Both were clinical leaps that advanced the quality of care for patients, but these two technologies evolved separately. Insulin pumps utilized a set algorithm to administer insulin that did not allow users to adjust their settings.

Although glucose monitors could provide accurate data on timing and dosage required, these proprietary devices could not interface with each other and allow those who had Type 1 diabetes to automatically regulate the administration of insulin based on the monitor’s data. Around 3.5 million people have their quality of life significantly impacted by Type 1 diabetes, yet medical bureaucracy, regulations and a lack of interest by medical companies meant that this had no solution available on the commercial market.

Items used in the Open Artificial Pancreas System. The high availability of powerful general purpose computing technology, combined with the ability to instantaneously collaborate irrespective of geographical barriers, have opened the doors to a world where we no longer need to rely on large medical companies to deliver solutions to medical problems. (Source)

In 2014 a group of hackers began working on solving this problem, using specific models of glucose pumps. Through a technical exploit, it was possible to override its default algorithm and supply external commands to control insulin administration. Using open-source code and a homemade rig of freely available electronic parts, the hackers created the Open Artificial Pancreas System. This project, whose slogan is “#WeAreNotWaiting to make the world a better place,” made freely available to everyone the code, instructions and component list that allowed even non-tech-savvy Type 1 diabetics to assemble a medical rig that not only was able to automatically administer insulin, but also allowed the user to customize the settings utilized in line with their personal circumstances and body response. Although this same solution became commercially available years later, it still costs around six times the price of the solution created by the Open Artificial Pancreas System, which lives on today.

A small group of people decided to solve a pressing problem that was not addressed by the commercial market. By collaborating in their spare time using the internet to interface with like-minded individuals worldwide, they developed a solution to a debilitating problem affecting 3.5 million people’s lives, that a $100 billion industry could not and gave away the solution for free. This is the power of peer-to-peer production and the collaborative economy to solve problems that the commercial market is not fit to solve. It is an example of its ability to harness even a small amount of the world’s untapped productive potential and turn it towards creative ways to solve problems that conventional economic models never will. As was the case with the gradual influence of internet-based businesses, an unfathomable amount of productive capacity that has not been able to find expression within the confines of the current paradigm will gradually start to dominate the world’s productive output via the collaborative economy. Human beings will work directly with human beings on things because they find them interesting, engaging and meaningful, rather than their potential to generate profit.

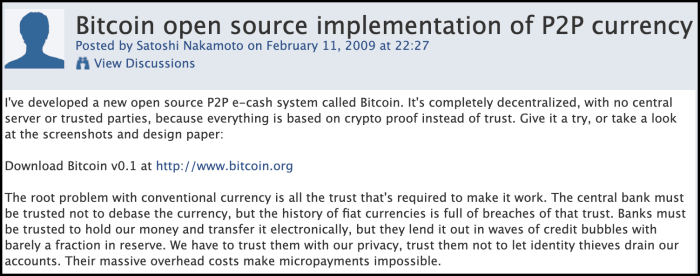

Bitcoin is a technology created in response to human problems, rather than the potential to exploit a market opportunity or generate profit. (Source)

This should be familiar to those who play music, participate in sport or are involved in any number of other hobbies in their part-time. For the majority, their motivations for doing these things are not financial, but that they can express themselves through it — who they are and what is important to them.

People don’t do these things because they make money; they make money so they can do these things.

Wikipedia, Linux, 3D printing, and BitTorrent are just a few examples of how this dynamic has already changed our world significantly. Bitcoin is the first money born out of this social shift, an open-source monetary network born in response to human problems rather than a market opportunity to generate profit. Bitcoin is money that is not optimized to be a tool for intermediaries to extract value but to remove them from the conversation. Its value is that it is open to anyone and relies upon their voluntary participation.

The emergence of crowdfunding platforms are one example of how the collaborative economy can provide an economic foundation for non-profit-generating endeavors to bootstrap themselves. However, as anyone from a country unable to access first-world banking services, or even a Canadian trucker will tell you, their fundamental problem is that they are closed networks, controlled by firms whose existence is centered on generating profits and excluding anyone who jeopardizes this bottom line. We lack a type of money that is philosophically aligned with peer production and the collaborative economy, an open-source monetary instrument that is not the proprietary property of any one company, nation or person. We need a payment protocol, not payment platforms.

As we have seen with the Open Artificial Pancreas System, the power of collaborative production comes from realizing the efficiency and productive capacity to be gained from removing profit from the equation. Instead of the control and monopoly on creation that comes from the need to protect profits in the traditional proprietary market model, collaborative models are now giving the ability to create to those for whom the need, motivation, and creativity is greatest, those who would voluntarily create for free, or even pay to do so. It is based upon the principle that greatest good comes not from building a lucrative monopoly and then incentivizing people to produce by paying them money, but what spontaneously emerges from removing the barriers preventing human beings from freely and voluntarily working with one another on what is most meaningful to them.

Ike Turner and The Kings of Rhythm (Source)

The Kinks (Source)

In 1951, a musician named Willie Kizart was on his way to the recording studio to record a song “Rocket 88” with Ike Turner’s Kings of Rhythm. On the way to the studio, his guitar amp fell off his car, and the speaker was damaged, adding a harsh, fuzzy tone to his guitar when he plugged into it at the studio. Ike decided he liked the sound and chose to keep it in the mix of the final recording, what is generally considered the first-ever rock ‘n’ roll record. Years later, another musician, Dave Davies, playing in a band called The Kinks came across the track. He found the tone so refreshingly different and aggressive he tried to emulate it, eventually resorting to cutting the speaker cone of his guitar amp with a razor blade. He used this amp to record the song “You Really Got Me” in 1965, which reached number 1 on the Official Charts Company list in the UK and reached a much larger audience, inspiring an entire generation of up-and-coming musicians to copy the sound of the distorted electric guitar. Today when we think of the guitar, we don’t think of the classical instrument that has existed for hundreds of years. We think of rock ‘n’ roll, the electric guitar and the sound popularized by Ike Turner, The Kinks, and thousands of teenagers spending hours of their spare time in garages trying to emulate them.

Rock music and our concept of the guitar today weren’t stimulated by profitability, the search for a market opportunity, the invention of proprietary technology or because a corporation decided this was the future of the guitar. It did not come from the top down but from the bottom up, spontaneously emerging from the spare time of human beings interfacing directly with each other on things that transcend financial return. Its resilience, popularity and longevity come precisely because it is not a proprietary product created to ensure a revenue stream but instead an idea owned by anyone and no one, and which anyone is free to reinterpret or improve on; this is something that includes, rather than excludes people. For the overwhelming majority of musicians, playing music is not the most profitable activity in their life, or it is in fact their biggest expenditure. They don’t do it for money, they do it because the act of creating something that has soul, that has meaning and resonates deeply with you, and then sharing it with the world is a fundamentally human compulsion.

Bitcoin’s greatest asset is that it connects to this compulsion. Bitcoin humanizes money. It changes it from a closed system whose levers are only in reach of a privileged few to an open one, dependent solely on shared resources that are free for anyone to inspect, modify or interpret. No one has the right to define what Bitcoin means or who has the right to participate in it any more than rock ‘n’ roll.

There is no CEO or official spokesperson of Bitcoin; it is controlled by everyone and no one. No one makes the rules in Bitcoin — we all do. We individually and collectively can decide how Bitcoin is used, and if the existing options do not suit us, we are not limited to those presented to us on a store shelf by a corporation or state; we can make our own, in collaboration with anyone anywhere in the world.

Samourai, Wasabi and JoinMarket have, without the permission of anyone, given everyday users the tools to use Bitcoin in a more private fashion and to cooperate to improve their anonymity. Innovations like the Lightning Network were born from the imagination of individuals working together in their spare time on something that interested them, then honed and brought to fruition by a team of largely voluntary workers.

NO2X and BTCPay are clear demonstrations of how easy it is for motivated users to deny corporations and well-resourced cabals the ability to dictate how we must use Bitcoin, to filter its utility and meaning through their lenses or co-opt it for their own needs. Bitcoin is money of the people, for the people. The future of Bitcoin — its form, utility and significance for our world, and most importantly, its soul will not be decided by companies or states in secret behind closed doors; it will be decided by human beings, working directly with other human beings.

Technology creates social context. Some things become easier and cheaper, others are harder and more expensive to do or to prevent under different technological conditions. Today much of our personal and financial expression happens through technology and software. The decisions made in the design of that software, what they incentivize or allow and what they prevent or discourage, subtly influence the conversation, whether that be in words themselves or the economic language of money and value.

Bitcoin is the financial manifestation of the collaborative economy, a technological revolution that enables anyone to speak freely and to choose the context of this conversation. In the context of Bitcoin lobbying a senator, asking permission from a bank or corporation to open an account or add a feature or creating a company with the correct licenses and regulatory compliance make as much sense as asking a school teacher in 1965 if you can have permission to play in a rock ‘n’ roll band. These social constructs exist to exploit value and dehumanize us by keeping individuals separated from directly coordinating with each other, by forcefully making themselves arbiters through which all communication or cooperation with others must take place, and whose language we must adopt, lest they silence us and take away our means to communicate with others altogether. In contrast Bitcoin offers a monetary technology that allows us to converse in the language of value openly, without interruption, and change the conversation when it does not serve our best interests.

Bitcoin will succeed not just because it is the best monetary technology, but because it speaks to something fundamental about the human condition — the need to freely, openly, and directly express ourselves and connect with other human beings. Bitcoin will succeed because it is fundamentally human.

Article txid: dc95dda1e4b5d08da567f4a1a8a494fe0f7a8e8dbeccfba1d9e22a16ba19f148

This is a guest post by CoinsureNZ. Opinions expressed are entirely their own and do not necessarily reflect those of BTC Inc. or Bitcoin Magazine.

[ad_2]

Source link