[ad_1]

Last December, South Korean semiconductor company Magnachip reluctantly announced the demise of its proposed $1.4bn merger with Chinese private equity firm Wise Road Capital.

Apart from its listing on the New York Stock Exchange and a nominal corporate presence in Delaware, Magnachip has no substantive operations — in manufacturing, research and development or sales — in the US.

But that did not stop the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States, a body initially set up in the 1970s to screen the purchase of US strategic assets by OPEC countries, from intervening in the merger.

In a move that took the global semiconductor industry by surprise, Cfius ruled that the transaction posed a potential risk to US national security, effectively killing the deal and casting a chill over the sector.

“Cfius has traditionally been involved in traditional security issues like ports and infrastructure, and yet it blocked the takeover of this relatively small chip firm that had hardly any US presence at all,” said Chris Miller, assistant professor at Tufts University and author of Chip War: The Fight For The World’s Most Critical Technology. “That was a really important signal for the entire industry.”

The Magnachip case is an example of how mounting US-China tensions are affecting chipmakers, which are increasingly being pressed to align with Washington as it seeks to counter China’s rise as a technological power.

The companies are vying for billions of dollars in US grants through the $280bn Chips and Sciences Act and do not want to be caught out by restrictions from an increasingly hawkish White House.

The Financial Times reported this month that Korean semiconductor titans Samsung Electronics and SK Hynix are re-evaluating their investments in China in response to “guardrails” in the legislation that prohibit recipients of US federal funding from expanding or upgrading their advanced chip capacity in China for 10 years.

Competitors including Taiwan’s TSMC and US chipmakers Intel and Micron, all of which have manufacturing operations in China, are also under pressure to boost domestic US production while making it harder for Beijing to obtain advanced semiconductor technology.

The pressure is likely to build as the US attempts to rally allies Korea, Taiwan and Japan behind a “Fab 4 chip alliance” designed to co-ordinate policy on research and development, subsidies and supply chains.

Korean chipmakers, historically reluctant to take sides in the technological rivalry between the US and China, have acted as a bellwether for the direction of the global semiconductor industry.

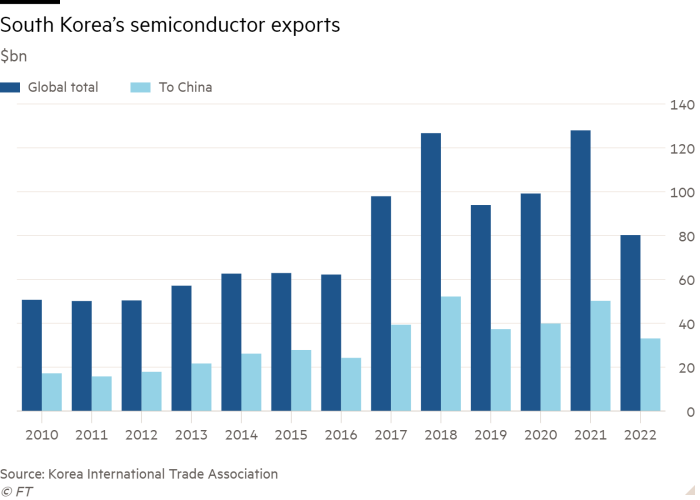

Samsung and SK Hynix have boosted investments in US production facilities even as they remain heavily exposed to the Chinese market. South Korea exported $50bn of chips to China last year, up 26 per cent from 2020 and accounting for nearly 40 per cent of the country’s total chip exports, according to the Korea International Trade Association.

But they share a near-total dependence on a small number of US, Japanese and European chip designers and equipment makers for the technology required to produce advanced chips, giving Washington leverage over what Miller described as the “main choke points in the semiconductor production process”.

Those companies include US chip designers Cadence and Synopsis, Siemens-owned Mentor Graphics, American equipment makers Applied Materials and Lam Research and ASML in the Netherlands, which makes the extreme ultraviolet lithography tools needed to produce cutting-edge Dram memory chips.

“China has the market, but the US has the technology,” said Yeo Han-koo, who served as South Korea’s trade minister until May. “Without technology, you have no product. Without a market, at least you can find a way to diversify and identify alternatives.”

Neither Samsung nor SK Hynix, which both specialise in memory chip production, manufacture their most advanced semiconductors in China.

China’s largest chipmaker Semiconductor Manufacturing International Corp announced last month that it had started shipping advanced 7-nanometre semiconductors. However, analysts said that without access to the world’s most sophisticated equipment, SMIC would struggle to close the gap with Samsung and TSMC, which are major global suppliers of 5nm and 4nm chips.

A person close to TSMC, which dominates the global market for foundry chips, said the US bill was unlikely to have a dramatic effect as the Taiwanese government already had restrictions on producing advanced chips in mainland China.

But Dylan Patel, chief analyst at SemiAnalysis, said that US guardrails on upgrading or expanding companies’ Chinese operations would still have an impact.

SK Hynix and Samsung would probably only maintain their existing investments, said Patel. “As a result, the share of their production in China is likely to reduce substantially over time,” he said.

The dilemma for Korean and other chipmakers is how to execute their pivot away from China and towards the US without provoking a backlash from Beijing, which has grown increasingly vocal in its opposition to what US officials describe as “friendshoring”.

“Decoupling with such a large market is of no difference from commercial suicide,” read an editorial last month in the Global Times, a Chinese state-owned nationalist tabloid. “The US is now handing South Korea a knife and forcing it to do so.”

Yet Patel said China’s continued dependence on the chips and technologies from foreign groups meant that its leverage was limited. “Beijing needs these chip imports for their own manufacturing industries. What are they going to do, stop having electronics manufactured in China?”

He said Washington could increase the pressure further by banning the export of chipmaking equipment used to manufacture advanced Nand memory chips to Chinese plants, including those owned by foreign companies. Samsung and SK Hynix both have Nand memory chip plants in China.

David Hanke, partner at Washington law firm ArentFox Schiff, who advises multinationals on China competition issues, said that chipmakers would be wise to heed the spirit of the Chips Act and not just the letter of the legislation itself.

“How much a company has been contributing to China’s technological development will be scrutinised,” said Hanke, noting that grants to chipmakers would be reviewed every two years by the US Department of Commerce.

“There will be a big optics problem for companies that play it too close to the edge of what this legislation allows.”

He added that companies should also consider the possibility that Washington will take an even more hawkish turn in the near future. Republicans are tipped to recapture the House and possibly the Senate in November’s midterm elections.

“When it comes to circumventing US regulations, China moves like water around rocks. So it shouldn’t come as a surprise if people on Capitol Hill start to say in a year or two’s time that the present guardrails were too weak.”

Additional reporting by Kathrin Hille in Taipei

[ad_2]

Source link

Comments are closed.