[ad_1]

How to Make Up after a Fight

Therapist Terry Real is a master teacher in how to build healthy communication with your partner. He’s also a self-described fighter. Which means that, yes, even a relationship expert as great as Real sometimes argues with his spouse. They’re just really good at making up.

-

Some important context: All of the below applies after you’ve given each other space to cool off. Maybe you needed an icy glass of water or a lap around the block to clear your head. When that’s taken care of—and you’ve checked in with your partner to make sure they’re ready, too—come on back. Here’s how to talk it out.

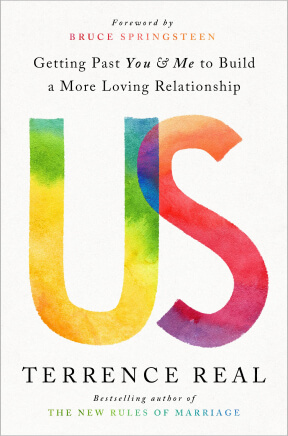

If you’re reading this on June 9, one more thing: Gwyneth is hosting a live book launch event with Real tonight at 7 p.m. Eastern Time (4 p.m. Pacific), and you can tune in virtually on Vimeo. Your ticket includes a signed copy of Real’s new book, Us: Getting Past You & Me to Build a More Loving Relationship.

-

![Terrence Real Us: Getting Past You & Me to Build a More Loving Relationship]() Terrence Real

Terrence Real

Us: Getting Past You & Me to Build a More Loving Relationship

Bookshop, $25SHOP NOW

From Us: Getting Past You & Me to Build a More Loving Relationship

Now that you’re centered and your partner is attentive, go through the four steps of the feedback wheel: what happened, what you made up about it, how you felt about it, and finally, what you’d like now.

Back when our kids were little, Belinda might have said to me, for example:

Terry, you said you’d be home by six and you arrive at 6:45, no message or text, while I sat with the kids waiting for dinner.

What I make up about that is that you still have some narcissistic traits and that you value your time over ours.

I felt sad, lonely, fearful of the impact on our children, hurt, and angry.

What I’d like now is for you to apologize to the kids, and to me for that matter. And tell me what you’re going to do to not repeat this pattern.

Notice that each step of the wheel is complete in just a few sentences. Be concise. And here are two more important tips. First, when you share your feelings, be sure to share your feelings, not your thoughts—keep them separate. “I feel like you’re angry” doesn’t cut it. Better would be “I make up that you’re angry and about that I feel.” I once had a Boston Southie say to his girlfriend, “I feel like you’re an asshole.” Then he looked at me. “Better, doc?” Hmm.

There are seven primary feelings: joy, pain, anger, fear, shame, guilt, love. Stick with those.

The second tip takes a bit of practice to execute. When you share your feelings, skip over the emotion that first comes to you, your go-to emotion, and lead with others. Belinda and I are both fighters. Our knee-jerk response will be anger. But recall that when Belinda gave me feedback about my being late, she put her anger last, not first. More specifically, if you are used to leading with big, powerful feelings, like anger, or indignation, soften up—reach for and lead with your vulnerability. Find the hurt. Conversely, if you lead with small, timid, insecure feelings, find your power. Where is your anger, the part of you that says “Enough”?

Here’s the principle: Changing your stance changes the dance between you. The shift from indignation to hurt, like the shift from tepid complaint to empowered assertion, will quite often evoke a different response than the usual. Try it. Change what you do on your side of the seesaw and watch what happens. Take the risk of leading with a different part of you—vulnerability for the righteous, assertion for the timid— and then step back and observe.

Once you’ve given your feedback, you’re finished. Let go. Detach from outcome, as they say in Alcoholics Anonymous. On Tuesday your partner answers with generosity and accountability.

On Thursday he tells you he’s in no mood for your bullshit. Tuesday is a good day for you, for your partner, and for your relationship. Thursday is a terrible day for your partner, a mixed day for the relationship, and still a great day for you. You did a fine job of speaking. That’s all you’re in charge of. Don’t focus on results. Instead, focus on how well you handle yourself. Focus on your own relational performance.

Listening with a Generous Heart

Okay, so let’s say you’re the one hearing feedback from your partner—now what? Yield. Don’t get defensive, or go tit for tat, or any of that Adaptive Child behavior. You, the listener, also need to be centered. You too need to remember love. What can you give this person to help them feel better? You can begin by offering the gift of your presence. Listen. And let them know they’ve been heard. Reflect back what you heard.

If you’re at a loss, just repeat your partner’s feedback wheel. In the case of my lateness, I might say to my wife, “Belinda, what I hear is that you waited with the kids while I came home late; you imagine it’s my narcissism; you had a lot of feelings about it—hurt, concern for the kids, anger—and you’d like an apology and a plan.” Is that reflection comprehensive and perfect? No. Some couples therapies call for exquisite reflecting. We don’t. If you are the speaker, and the listening partner has left out important things or gotten something seriously wrong, help them out. Gently correct them, and then have them reflect again. But don’t be overly fussy. Serviceable is good enough.

Now that you’ve listened, you need to respond. How? Empathically and accountably. Own whatever you can, with no buts, excuses, or reasons. “Yes, I did that”—plain and simple. Land on it, really take it on. The more accountable you are, the more your partner might relax. If you realize what you’ve done, if you really get it, you’ll be less likely to keep repeating that behavior. And conversely, not acknowledging what you did—by changing the subject, or denying, or minimizing—will leave your partner feeling more desperate.

Now, here’s an interesting thing to notice. If you are the speaker, it pays to keep it specific. The feedback wheel is about this one incident, period. Most people go awry when they escalate their complaints, moving from the specific occurrence to a trend, then to their partner’s character. For example: “Terry, you came late.” (Occurrence.) “You always come late.” (Trend.) “You’re never on time.” (Trend.) “You really are selfish!” (Character.) When the speaker jumps from a particular event to a trend (you always, you never) to the partner’s character (you are a…), they render their partner ever more helpless, and each intensification feels dirtier.

Now, notice that if the speaker escalates from incident to trend to character, each move makes things worse. If, by contrast, the listener moves up the ladder, outing himself, each move up feels wonderful to his partner: “I did this. It’s not the first time I’ve done it. It is a character flaw I’m working on.” On a good day I might answer Belinda, “Yes, I was late. I’ve kept you and the boys waiting on several occasions. I think it’s a vestige of my narcissism that I need to work on.” Now, that’s a satisfying apology.

Once you’ve reflectively listened and acknowledged whatever you can about the truth of your partner’s complaint, give. Give to your partner whatever parts of their request (the fourth step in the feedback wheel: what I’d like now) as you possibly can. Lead with what you’re willing to give, not with what you’re not—another simple practice that can help a lot. In my case, Belinda would say, “Terry, I want you to apologize to me, apologize to the kids, go back on medication, and go into psychotherapy three times a week to deal with your narcissism.” I want to say, or at least my Adaptive Child wants to say, “That’s ridiculous. I’m not doing all that.” In other words, faced with a bunch of requests, my first instinct is to argue. So here’s the thing—if you lead with argument, the odds are great that you will wind up in an argument. Instead, I take a breath and my Wise Adult answers, “Okay, Belinda. I will apologize right now to the kids and to you. I take this issue seriously and will conscientiously work on it. If I can’t change it on my own, we can talk about next steps and my getting help.” All the stuff I’m unwilling to do? I’m just going to leave that alone.

If your partner requests that you do X, Y, Z, you respond with, “Honey, I’m going to X and Z to beat the band.” Sell it. Put some oomph in it. You think, of course, that your partner will turn around and say, “Hey, what about Y?” But you might be surprised. Most often, if you put some energy into what you’re willing to give, it disarms our partners, and sometimes they’re even grateful.

And finally, for you both, let the repair happen. Don’t discount your partner’s efforts. Don’t disqualify what’s being offered with a response like “I don’t believe you” or “This is too little too late.” Dare to take yes for an answer. If what your partner is offering you is at all reasonable, take it, as imperfect as it may be, and relent. Remember, there’s a world of difference between complaining about what you’re not getting and having the capacity to open up and receive it. Allowing your partner to make amends and come back into your good graces is more vulnerable for you than crossing your arms and rejecting what they’re offering. Let them win; let it be good enough. Come into knowing love.

Once, back in the day, Belinda and I had been fighting for the better part of twelve hours. I was out of the house at a coffee shop. I called her one more time, hoping for a break in our dance. “Belinda,” I said, “are we okay? Should I come home?”

“You really are an asshole,” she replied, and I knew right away by her tone that we were all right.

We have a saying in Relational Life Therapy: “Tone trumps content.” Tone reveals which part of your brain you’re in, us consciousness or you and me consciousness. Belinda’s words were on their face abusive and name-calling. But her tone let me know that I was her little asshole, endearingly impossible. She had moved into knowing love, with no illusions and no minimizing of my faults, but acceptance, faults and all. It was time to come home.

Related Reading

Terrence Real is an internationally recognized family therapist, speaker, and author. He founded the Relational Life Institute, offering workshops for couples, individuals, and parents, along with a professional training program for clinicians to learn his Relational Life Therapy methodology. In addition to Us: Getting Past You & Me to Build a More Loving Relationship, he is the bestselling author of I Don’t Want to Talk About It, How Can I Get Through to You?, and The New Rules of Marriage. He offers a live online relationship program for couples around the world.

Excerpted from US copyright © 2022 by Terry Real. Foreword by Bruce Springsteen. Published by goop Press/Rodale Books, an imprint of Penguin Random House, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

We hope you enjoy the books recommended here. Our goal is to suggest only things we love and think you might, as well. We also like transparency, so, full disclosure: We may collect a share of sales or other compensation if you purchase through the external links on this page.

[ad_2]

Source link

Comments are closed.