[ad_1]

Everything You Need to Know about Beans

Take a closer look at how your favorite pantry ingredients are made and how to pick them, store them, and cook with them. This week, it’s all about beans. (But of course, feel free to revisit our pocket guides to vinegars and spices.)

Beans had a moment in early 2020. It makes sense that in a calamitous time we leaned on something as dependable, familiar, and comforting as a pot of beans. Beans have been relied on and even revered for thousands of years. In his book On Food and Cooking, food scientist Harold McGee writes, “A remarkable sign of their status in the ancient world is the fact that each of the four major legumes known to Rome lent its name to a prominent Roman family: Fabius comes from the fava bean, Lentulus from the lentil, Piso from the pea, and Cicero—most distinguished of them all—from the chickpea. No other food group has been so honored!”

But many of us are still puzzled by beans. Perhaps we’ve lost touch with those ancient kitchen instincts. So often people ask us: How do I cook them? What’s a legume? Why do they take so long? Do I soak them? When should I add salt? Aren’t they full of poisonous lectins? And then there’s the dreaded gas problem. We’ve gathered all the information you need, with additional guidance from a few bean experts and a nutritional perspective from our senior director of science and research, Gerda Endemann. Plus, many recipes to inspire your next pot of beans.

Legumes, Pulses, and Beans: What’s What?

It can get a little confusing. These three terms are all related but not the same. According to the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, legumes are a large family of plants that have pods. This includes peanuts, fresh beans, fresh peas, and soybeans. Pulses are the edible seeds from some of those pods, including beans, lentils, and peas. (Peanuts and soybeans are typically not considered pulses because they have a significantly higher fat content.) Pulses are commonly dried for long-term storage, like grains (another type of edible seed).

Cooking Dried Beans

There are many advantages to cooking a pot of dried beans. You can season them however you like and cook them to your desired doneness and textural preference, and you’ll be left with the pot liquor (also called pot likker). This is the prized, deeply flavorful bean broth, which you can use as you would any other stock or broth. Whatever you do, do not toss this liquid gold.

-

Always rinse and sort dried beans for dirt and small rocks (they do indeed come from a field).

-

Cover your beans well with water, about 3 cups for every 1 cup of beans (you could technically use stock, but a pot liquor made from water will turn out so flavorful, it’s almost a waste to use good stock here).

-

Add aromatics. Some combination of onion, garlic, celery, carrot, and herbs or spices (like bay leaves, fennel seed, or allspice).

-

You can add kombu—a sea vegetable that has an enzyme that can help break down some of the gas-producing sugars in beans.

-

A little fat is nice, too (olive oil, duck fat, even rendered bacon grease left over from breakfast will do).

-

Some folks like to add smoked or cured meat—ham hock, turkey leg, guanciale—for depth and umami. You could also add smoked dried chilies to give a similar effect.

-

Bring it all to a roaring boil for at least 10 minutes, then reduce the heat and let simmer until tender. This part can take a few hours, depending on the size of the bean.

-

Leftover cooked beans can be stored in the fridge or freezer in their pot liquor for a variety of future cooking projects: dips, soups, stews, chili, and refried beans.

There is no one way to cook dried beans, but there are a few best practices we like to keep in mind.

That is a very general and adaptable method, but there are some burning points of contention in the bean world.

To Soak or Not to Soak?

Soaking beans can help soften the skin (also known as seed coat) of the bean. This helps water penetrate to the interior of the bean and cook it more quickly and, according to some, more evenly. There are two ways to soak. You can cover your beans with cold water for several hours or overnight. Or you can cover the beans with boiling water for a much shorter period of time. But soaking beans isn’t necessarily better.

According to On Food and Cooking, soaking beans before cooking can reduce cooking time by 25 percent, and a quick hot soak can even potentially reduce the gassiness of beans. However, McGee also writes that it can “leach out most of the water-soluble vitamins, minerals, simple sugars, and seed coat pigments: that is, nutrients, flavor, color, and antioxidants.” When J. Kenji López-Alt did his exhaustive deep dive on beans for Serious Eats, he found similar results. Not only did some of that quintessentially bean-y flavor get lost, but certain thin-skinned beans, like black beans, actually had a better texture when cooked without presoaking. Steve Sando, owner of the beloved heirloom bean brand Rancho Gordo, writes on his blog, “I’ve seen it claimed that I’m against it. This isn’t quite true…. But if I suddenly have the whim to make beans, there’s no way I’m not making them because I had forgotten to put some beans to soak.” Most Rancho Gordo employees begin as avid soakers but eventually skip it.

When to Salt?

There is a misconception that salting your beans will delay their cooking. It appears that is not the case. If you soak your beans: Salt your soaking water, then discard the water, give the beans a rinse, and cook them in fresh water with a good pinch of salt. McGee says that salting the soaking water might actually speed up the cooking process. He explains that the sodium displaces magnesium from fibers (pectins) in the cell wall, weakening the cell wall, which helps soften the beans. If you don’t soak: You can still liberally salt your pot and enjoy well-seasoned beans because of it.

What About Pressure Cookers?

If dried beans are your passion and you’re short on time, a pressure cooker is the way to go. These hermetically sealed cookers work by trapping in the water vapors from boiling liquid, which raises the boiling point from 212°F to about 250°F. This combination of steam and boiling water and the extremely high temperature makes for very quick cooking. A pot of beans that might take hours on the stove can take about 30 minutes in a pressure cooker, and if soaked and presalted, it can take as little as 10 minutes.

Cooking with Canned Beans

Some incredible meals can be made with canned beans. They’re undeniably convenient, especially if you’re short on time. They’re an affordable pantry staple with a long shelf life, and they can be used in so many ways. Nutritionally they should have the same value as dried beans (they once were dried beans, after all).

There are two small downsides to using canned beans. One is that they’ll never be as flavorful and well-seasoned as a homemade pot of dried beans. You can get around this by rinsing them and giving them extra time to cook in your soup or sauce so they really absorb whatever aromatics and seasonings you’re working with. The other thing is that they can be quite soft out of the can, making them a little mushy in a cold salad preparation—if you cook a pot of dried beans yourself, you’ll have a bit more control over texture.

An upside for canned chickpeas in particular, though: aquafaba. The liquid from canned chickpeas can be used as an egg substitute to make everything from vegan meringues to vegan aioli (Gwyneth got very into it while making The Clean Plate). So don’t send it down the drain.

Lectins and Other Digestive Issues

Many people avoid beans not because of their cooking time but because they can be difficult to digest. We asked Gerda to explain why beans have the effect they do and if it’s possible to avoid it.

GERDA SAYS:

Beans taste great, are satisfying, and are a good source of protein fiber, vitamins, and minerals, including iron. But they get bad press because of their lectin content and the gassiness they tend to cause. The first problem is easy to deal with.

To inactivate lectins, cook your beans well by boiling or pressure-cooking. The reason you want to do this is that lectins are hard to digest if they aren’t well cooked. Undigested lectins can damage the intestine and cause allergic reactions and inflammation. Sprouting can’t be counted on to do the whole job.

As far as gas, the age-old problem is how best to incorporate beans into our diets without discomfort. This is especially important for those who don’t eat animal products. As a good source of iron, beans are important foods for vegetarians, who are more likely than meat eaters to be low in iron. Unique Hammond, the founder of The Bean Protocol, suggests building up a tolerance for digesting beans and eventually including them in most meals. She says that as little as two tablespoons may be a good starting place.

We’ve blamed gas on the unique fibers in beans, the small oligosaccharides, including raffinose, that can turn into methane and hydrogen gases. McGee says that sprouting and fermenting can help lower the amounts of these fibers. There is some evidence that supplements containing an enzyme called alpha-galactosidase—such as Beano—may help digest these oligosaccharides in some cases. But we know this isn’t a perfect solution, possibly because there are other kinds of gas-forming fiber.

Fibers in the cell walls, pectin and hemicellulose, may also be gas forming. So we need to think about how our cooking methods affect the digestibility of these fibers. McGee recommends long cooking times to help with this. You can try supplements containing enzymes that may help break down hemicellulose (hemicellulase) and pectin (pectinase), as well as oligosaccharides (alpha-galactosidase).

-

Try to integrate more beans into your diet slowly so your body can adjust to them.

-

If using canned beans, try Eden brand. Eden has a thorough soaking, steam blanching, rinsing, and pressure-cooking protocol to help inactivate lectins. It also adds kombu to its canned beans.

-

If using dried beans, cook them for a long time—either on the stove top or in a pressure cooker. Long cooking times can inactivate the lectins in beans, making them more digestible, and can help break down the fibers that may cause gas.

-

Opting for sprouted beans can also potentially help offset gas.

To sum it up, there are a few strategies for limiting digestive problems with beans:

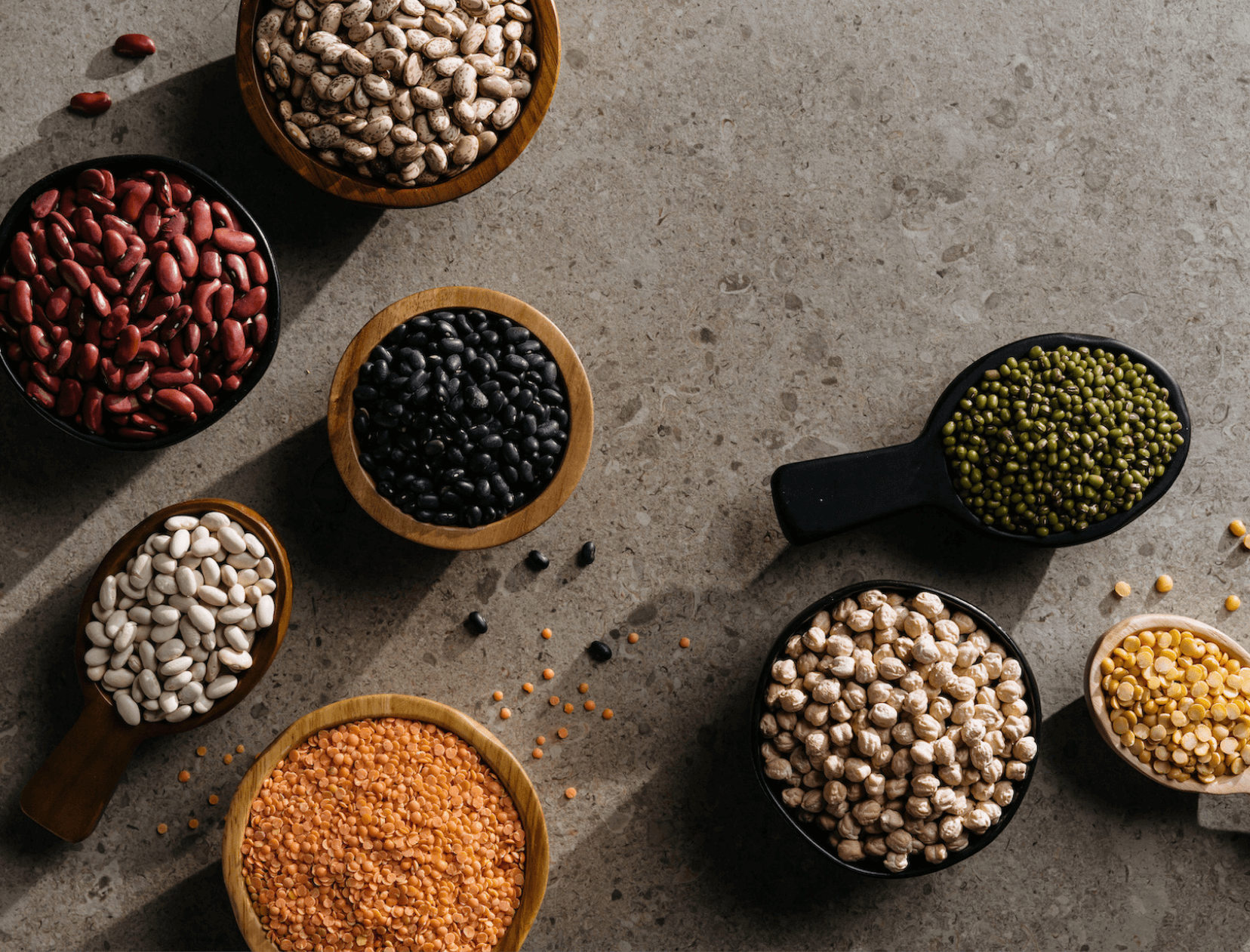

Meet the Beans

This is not a complete list by any means, but these are the beans we use most often in our test kitchen, and they’re found most frequently in our recipe archives.

CHICKPEAS

By far our most-used bean. They kind of do it all. We can make them crispy. They have a sturdy exterior, making them great for cold salads and soups because they can hold their shape without disintegrating. And they’re the creamy base of hummus and our favorite mock-tuna smashed chickpea salad.

WHITE BEANS

There are three beans people are usually referring to when they talk about white beans: cannellini beans (also called white kidney beans), navy beans, and great northern beans. There are some slight differences in size, texture, and flavor. Cannellini is the biggest, navy bean is the smallest, and great northern is in between. But they can be used interchangeably without issue. They are mild and creamy when blended into dips and puréed soups but equally well suited for salads and pasta dishes.

BLACK BEANS and PINTO BEANS

While both of these beans are classic in Latin American cooking, they’re not the same. Black beans are smaller, slightly sweet, more assertive in flavor. Pintos are larger and more earthy, and they’re good at absorbing whatever you’ve seasoned them with. Both are excellent refried and in soups, stews, and chilis.

KIDNEY BEANS

These large kidney-shaped beans have a striking red color and are popular in soups and chili. Their firm texture also makes them a good candidate for cold salads.

LENTILS

There is a lentil for everyone. There are firm lentils that hold up well in both hot and cold preparations, like black beluga and French du Puy. There’s the classic brown lentil, which is a reliable all-arounder, commonly used in lentil soup. And red lentils, also known as masoor dal, cook down into a lush, creamy texture, for excellent soups and dips.

Heirloom Varietals to Look For

There is an amazing tradition around heirlooms and seed saving. Farmers or gardeners will save seeds from specific, rare, or even endangered fruits, vegetables, grains, and beans that haven’t been cross-pollinated with other varietals. They’re quite special, and unlike their mass-produced, widely available counterparts, they have history and old-world charm. They’re coveted for flavor and texture, instead of being selected and propagated for their ease of growth and high yield, as most industrial crops are. In the hands of experienced growers, the heirlooms can create a one-of-a-kind culinary experience.

One of the most popular sources for these specialty beans is the aforementioned Rancho Gordo in Napa, California. Its following is huge and intensely loyal: The famed quarterly bean club membership even has a wait list. We’ve yet to have a Rancho Gordo bean that we didn’t love, but if you come across a bag of the Marcella, Scarlett Runner, or Santa Maria Pinquito beans, grab without hesitation.

RECIPES WHERE BEANS SHINE

Escarole and White Beans

Bitter greens, like escarole, balance out the richness of cannellini beans and the salty, umami-rich anchovies.

Curried Chickpea Salad

A plant-based riff on one of our favorite deli-inspired lunch dishes. Chickpeas are hearty and serve as a nice earthy-neutral canvas for ginger, lime, garlic, and curry powder.

Chickpea Cacciatore

We took all the savory goodness of traditional chicken cacciatore and used chickpeas instead.

Grilled Kale with Chickpeas and Pickled Onions

Grilling the kale first adds texture and smokiness. Chickpeas give some heft. And pickled onions bring some nice acidity.

Eggplant and Chickpea Rice with Cilantro and Yogurt

This dish comes together quickly and easily, and it scratches the itch of weeknight takeout while taking care of those leftover greens you have in your fridge.

Kale Caesar with Chicken and Crispy Chickpeas

The star of this salad is the dressing—it’s a creamy cashew version that might be better than the dairy- and egg-laden original. The texture of cashews almost mimics the delightful crumbliness of Parmesan.

Harissa-Roasted Vegetables and Chickpeas with Tahini Yogurt

Crispy chickpeas, creamy sweet potato, and charred cauliflower, all tossed in a garlicky harissa paste and finished with a drizzle of cool tahini yogurt.

Smoky Black Beans and Vinegar-Braised Collards

The beloved beans and rice bowl gets a little oomph from smoked paprika and bright, vinegary braised greens.

Perfectly Cooked White Beans

Cooking dried beans is so easy in the pressure cooker, and once you have them cooked, they’re great to have on hand for the week.

Green Chili Stew with Chicken and White Beans

A cross between New Mexican green chili stew and white chicken chili.

Cauliflower Black Bean Scramble

This egg alternative looks like the real thing thanks to a little dash of turmeric. It’s super savory, and the beans and avocado make it a filling breakfast.

Black Bean and Sweet Potato Tostadas

Creamy black beans and roasted sweet potatoes on crispy grain-free tortillas.

Bean Stew with Kale and Escarole

Hearty soups always seem to taste better the second day: This turkey sausage stew delivers that bang in seven idle hours.

Cannellini Bean and Quinoa Burgers

Served stacked or on a platter, these vegan and gluten-free burgers are easier to make than they look.

Three Bean Salad with Sautéed Chard

A great dish to throw in a jar or container and take to work for a healthy room-temperature lunch.

Black Bean Chipotle Burgers

The black beans are delightfully deceiving, making this vegan version look like the real thing—and taste even better.

Red Lentil and Caramelized Onion Soup

Combining these earthy gems with the deep, roast-y, slightly sweet flavor of caramelized onions will warm your stomach and keep you satisfied.

Want to Learn More about Everyday Ingredients?

-

New-wave sweeteners: decoded.

-

This eye-opening piece on cooking with fat has a handy chart with oil types and smoke points.

-

This guide to cooking with leafy greens will make eating your veggies way more delicious.

We hope you enjoy the books recommended here. Our goal is to suggest only things we love and think you might, as well. We also like transparency, so, full disclosure: We may collect a share of sales or other compensation if you purchase through the external links on this page.

[ad_2]

Source link

Comments are closed.