[ad_1]

The Pony Express was the Old West’s version of Amazon, FedEx, or UPS—whichever delivery service you prefer. Of course, the riders of the Wild West’s horseback mail delivery service couldn’t guarantee they could get your letter to its destination in a day or anything. But what the riders and relief station workers were able to do was pretty unique nonetheless.

The Pony Express was officially known as the Central Overland California and Pikes Peak Express Company. It began operations on April 3, 1860, with the singular purpose of carrying mail via horseback from its eastern terminus in St. Joseph, Missouri, to its western destination in Sacramento, California. Along the way, there were relief stops spaced out roughly every 10-15 miles (16-24 kilometers). Riders would show up at each stop, saddle up with a fresh, rested horse, and be out on the way again to the next checkpoint as quickly as possible.

Through that difficult route, riders could get messages from Missouri to the west coast in less than ten days. That was a major improvement on what had been months of slow, plodding travel through tough terrain. And while the Pony Express only lasted about 18 months due to financial troubles, its impact on Western culture is still felt today. The company’s riders are still seen as one of the most legendary and emblematic faces of Western horseback lore.

This list travels back to look at ten fascinating facts about the Pony Express. You may know about the mail delivery service in general, but these are interesting tidbits that go far beyond the surface-level focus most history books have on the ground-breaking company, its rise, and its eventual demise.

Related: Top 10 Grisly Tales From The American Frontier

10 Forget about Buffalo Bill (Probably)

William “Buffalo Bill” Cody famously claimed in his autobiography late in life that he was a Pony Express rider as a 14-year-old boy. Now, that would seem a tall claim for nearly anyone, considering the demands placed on those riders. Cody was a great horseman, though, so perhaps he was technically proficient at 14 to be able to ride on some of those journeys. But he was also one of America’s earliest and most audacious showmen, too. Thus, his claims about riding for the Pony Express are almost certainly a tall tale.

As historians point out now, Cody’s claim to once riding a record 384 miles (618 kilometers) in a single run is almost certainly false. One man did ride a 380-mile (611.5-kilometer) circuit in less than 48 hours (more on him below), but it wasn’t Cody. Not only did the Pony Express owners never produce any record of Cody carrying mail, but he was also documented as being in school in Kansas during the company’s very brief existence. It is very unlikely that he would have slipped out of school to take on Pony Express rides at all, much less work for them long enough to be the man trusted with a crazy 380-mile journey.

Still, Cody did his part to push the Pony Express into popular culture long after it was gone. The “Wild West” shows he put on with a traveling troupe nationwide told the tale of Pony Express riders and their exploits for decades. Well into the 20th century, Cody was pushing the legend of the Pony Express onto the public. In that way, he does deserve credit for keeping the short-lived circuit’s memory alive. But he wasn’t one of its riders when the real thing was going down in 1860.[1]

9 Weigh Before You Ride

Because speed was the name of the game with the Pony Express, the company needed its horses to be swift and its routes to be efficient. So, to ensure that would be the case, they instituted a very strict weight limit for their hired riders. After all, with horses going at a breakneck pace over miles-long stretches to deliver important messages and legal documents, speed was everything. A heavy rider would slow down a horse in the short run, wear it out in the long run, and potentially injure it—all of which would hurt the company’s biggest advantage in moving things quickly.

To that end, the Pony Express had a very strict 125-pound (57-kilogram) upper weight limit for hired horsemen. They would make riders step on a scale to ensure they didn’t go over the upper limit. And as soon as riders got too big to go, they were canned in favor of lighter (and very often younger) replacements.

That’s the other thing: Buffalo Bill may not have ridden the Pony Express when he was 14, as we just learned above, but many teenagers did! It wasn’t that unusual for teens as young as 14 to take the reins and ride the long circuit. The company loved it because the growing boys were certainly under the weight limit. And the pay was good for the dangerous rides, so the kids didn’t mind making some real coin to go on an adventure.[2]

8 And Take This Oath Too

Because the riders were so young, there was a natural worry that they weren’t trustworthy enough to get the job done. The pay helped quite a bit; the riders made monthly salaries, most often in the $100 to $150 range. That is nothing today, but that was a princely sum back then—especially for uneducated, unskilled horsemen. So along with the money came a requirement that the riders be of good character and consistent enough to deliver often important documents that needed to be moved fast.

Every rider who began his career with the Pony Express in 1860 and 1861 swore to quite an involved oath of loyalty to the firm and its leaders. In front of a current employee at a relief station or other hiring point, each rider would honor the company owners—William H. Russell, William B. Waddell, and Alexander Majors—in a serious, solemn way.

Each rider would piously say as follows: “I do hereby swear, before the Great and Living God, that during my engagement, and while an employee of Russell, Majors and Waddell, I will, under no circumstances, use profane language, that I will drink no intoxicating liquors, that I will not quarrel or fight with any other employee of the firm, and that in every respect I will conduct myself honestly, be faithful to my duties, and so direct all my acts as to win the confidence of my employers, so help me God.”

And from there, they were off to the races! The mere existence of the oath didn’t mean temptation never crossed the boys’ minds. Liquor was said to supposedly flow heavily at relief stations along the route, and it was common for riders to get falling-down drunk—and then go out to continue their journey. Still, the pledge at least offered a glimpse into how seriously the company took its duties delivering sensitive and important documents across the West.[3]

7 Relief for Relief Stations!

Knowing what we now know about the Pony Express, you might assume that riders had the most difficult job on the planet. But you’d be wrong! In fact, those who had to hang out at the relief stations, tend to the horses, and maintain the corrals for the company’s animals had decidedly more dangerous gigs. See, while riders always faced the risk of attack by both bandits and Indian war parties, they at least had the advantage of being on a really fast horse that could (theoretically) run away. Plus, since riders were always on the move, they were tough to track down depending on when and how quickly they moved through an area.

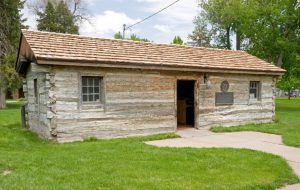

Relief station employees, on the other hand, were sitting ducks. These relief stations were spread out every dozen or so miles from Missouri to northern California, and each one was manned by a single person who couldn’t do much to keep away evildoers. The stations themselves were extremely crude, with dirt floors, pathetic sleeping quarters, and tiny, insignificant corrals for the company’s exhausted horses. Beyond that, because the stations quickly became well-known in an area, Indian groups and bandits knew exactly where to go if they wanted to wreak havoc.

Many of the relief stations were located in very remote sections of the frontier, and the employees tasked with caring for the horses there had little by way of defenses on hand. They had a bun, but they were often working alone. Warring Indian factions would sneak up in groups, plot attacks, raid horses, and kill employees. During the Pyramid Lake War alone in the summer of 1860, those attacks were so routine that more than a dozen stock hands at relief stations were slaughtered during those summer months in northern Nevada alone.[4]

6 Ride Really, Really Hard

Just a few weeks after the Pony Express was founded, one of their most legendary riders ever took his turn on the trail and soon landed in the history books. It was May of 1860, and Robert “Pony Bob” Haslam saddled up to go on a little ride. The plan was for him to ride from Friday’s Station eastward to Buckland Station in northern Nevada. That was a short 75-mile (120.1-kilometer) journey—and one that he made many times during his run for the company. But when the 20-year-old got to Buckland Station, he found something unfortunate: His relief rider scheduled to go on the next turn of the course was terrified that he’d be attacked by Paiute Indians.

The Paiutes were all over northern Nevada at the time, so the rider’s worries weren’t exactly unfounded. But it was a challenge, to say the least, that a hired man making good money to deliver important messages wouldn’t do his job. Without any other option and no other riders around at the relief station to take the man’s place, Pony Bob decided to get the whole thing done himself. He struck out from Buckland Station on a new mount and eventually completed a full 190-mile journey all the way to Smith’s Creek far in the east and made the scheduled delivery.

Then, he knew he needed to get home to where he started. So, he took a brief rest, swapped out another mount, and went all the way back to Friday’s Station. During the return journey, as if proving the exact point of the scared rider on the original run, Haslam had to ride right past a burned-out relief station. The Paiute Indians had just missed Pony Bob but had destroyed a relief outpost and hurt the firm all the same. Nevertheless, Haslam pressed on. Finally, he returned to Friday’s Station, successfully (and safely) completing the 380-mile trip. And the time was even more impressive: he did the whole thing in a bit less than 40 hours.[5]

5 And Go Really, Really (Really, Really) Fast

Undoubtedly, you’ve been doing some mental math regarding Pony Bob’s ride rate on that 40-hour journey. Well, he wasn’t the only Pony Express rider who liked to go fast. In the mid-19th century, the “snail mail” overland routes that took most mail to California were just that: fit for snails. The average trek to the west coast took about 25 days across the frontier. Or if you really didn’t need a response fast, you could send the stuff by boat. That would take months. So the Pony Express billed itself as that era’s version of Amazon Prime if you will.

The firm set up almost 200 relief stations all across the frontier. From Missouri to what is now Kansas, Nebraska, Colorado, Wyoming, Utah, Nevada, and California, these stations sat every handful of miles. They needed to dot the land as they did because riders would swap out mounts every couple of stations. Fresh mounts offered them that continued breakneck pace that those who paid for mail passage came to expect. Then, each rider would usually go anywhere from 75 to 100 miles on multiple horses before a new rider would grab the bag and pick up the slack.

In total, roughly 75 horses were used on each trip across the Plains and through the mountains. But relative to the slow overland route of the mail at the time, you really can’t complain about the results of the Pony Express’s adventuresome employees. They cut the mail time from well below half, sometimes even getting it down to a third as long as prior journeys. When Abraham Lincoln was elected and gave his inauguration address in March of 1861, the Pony Express record run came through: Lincoln’s address made it from Missouri to California in only seven days and 17 hours.[6]

4 Special Deliveries Only

Now that we’ve got you all excited over the amazing Pony Express, it’s time to hit you with the toughest fact of them all: it was really, really, really expensive. Even though the venture was partly subsidized, it struggled to make money and failed to secure a full government contract for mail delivery. Even worse, because it had such a long and tough route to run on every single trip, along with high risks posed to the riders, horses, and rest stop workers, it was a high-cost business.

To that end, the firm wouldn’t deliver ordinary mail. In fact, ordinary, everyday people very rarely used it to send anything at all. The costs of a single delivery were simply far too high for people to use it regularly. When the service first began, it charged $5 for every half-ounce of mail delivered. (Remember, weight on the back of the horse was a critical component of this endeavor!) That $5 was a lot of money back then; in fact, it was the equivalent of nearly $150 today! Could you imagine sending a half-ounce letter to somebody for $150? You wouldn’t do it!

Soon enough, prices dropped to $1 for a half-ounce of mail, but that cost (nearing $30 in today’s money) is still pretty steep for what you were sending and how much you could send. Because of that, the average letter writer wasn’t in the market to send or receive anything from the Pony Express. Instead, the service mostly ferried official government dispatches, important business documents, and significant newspaper reports. And even those were almost always printed on extremely thin, nearly see-through sheets of paper. Anything to cut down on weight costs![7]

3 Custom Saddlebags for Mail

The documents that did get shuttled off onto those infamous horses were always held safely and securely in a mochila. That’s the Spanish word for knapsack, and it was a special type of mailbag Pony Express riders used to store the important things they were carrying from station to station. The set-up was simple: The bag was draped over the rider’s saddle and then held in place by the rider’s weight. It fell across the horse’s backside and stayed there as the rider pushed toward the next relief station.

The mochilas were pretty sturdy in their own right. They could hold up to 20 pounds of documents and other cargo at a time. Plus, they held the rider’s timecard that he’d stamp at each destination to ensure he was making good time and keeping pace. They were padlocked, too, so that no ne’er-do-well could rip open a mochila and steal whatever valuable thing was being carried inside.

Then, when the rider got to where he was going, he dismounted, pulled the mochila off, remounted his next horse, and carried on with it. In most cases, riders could be off one horse and onto the next in a span of two minutes or less. The paces we’ve learned about here so far are nothing compared to the modern world, but the efficiency of those turnaround times was truly a sight to behold in the 1860s.[8]

2 It Was Never Profitable

Unfortunately for the men who founded the Pony Express and the agencies who came to rely on it to send out dispatches to the remote corners of America, the company was never profitable. Actually, that would be putting it lightly. From pretty much the very start, it proved to be a true financial flop. Thus, it only lasted about a year and a half before it went belly up. (Although, to be fair, another specific invention—which we will learn about momentarily—was what really helped hasten the Pony Express’s rapid demise.

Regardless, the actual numbers involved were staggering for the time period. Just a few weeks after the Pony Express started delivering mail and documents, the Pyramid Lake War broke out in northern Nevada. That was fought between the U.S. Army and the Paiute Indians, and it occurred right smack-dab in the middle of the company’s overland routes. So, from the start, service along that section of the route was suspended. In turn, the company started hemorrhaging cash over the Nevada-to-California deliveries they couldn’t make.

Then, over the next few months, the big failure came: They failed to sign up the federal government on an official mail contract. Without the guarantee of government contract money to deliver the mail, the firm had to try its best to cut down operating costs quickly. Because of the nature of their business, that was nearly impossible to do. And because the government wouldn’t subsidize them (remember the time period here; war was about to break out back east), the company was on its own. When the Pony Express was eventually forced to close up shop in October of 1861, it had run up about $200,000 in operating costs and only returned about $90,000 in revenues.[9]

1 Done in by the Telegraph

Competition didn’t come to the Pony Express by way of another overland mailing system. Instead, it came via technology. Even though the Pony Express was expensive to customers and bleeding cash for its owners, it survived for the year-and-a-half it did because there were simply no better alternatives. That all changed on October 24, 1861, when Western Union successfully completed the first transcontinental telegraph line at a station in Salt Lake City, Utah. With the Eastern and Western telegraph lines now working coast to coast, messages could be sent at a fraction of the cost and with a fraction of the trouble than the ponies were doing it through the overland route.

It didn’t even take a full week for the Pony Express to shut down after the Salt Lake City connection, either. A mere two days after the telegraph lines linked up, it was all over for the Central Overland California and Pikes Peak Express Company. To the Pony Express’s credit, its riders had delivered nearly thousands of pieces of mail and important documents during its 18-plus-month run across the West. But it was no match for the relentless push of technology, and today, it is merely one of many amazing legends of the Old West.[10]

[ad_2]

Source link

Comments are closed.