[ad_1]

When the Civil War started in 1861, men from all over the country rushed to fight for their respective sides. There was less for women to do, by comparison, as they simply didn’t engage in battle at the time. Sure, there were nurses aplenty helping out near the front lines and in war hospitals. And many more women assisted the war effort by doing things like servant work, domestic duty, and other labor-intensive jobs to help on the homefront. But one of the most interesting aspects of the time was the employment of a rare and disparate group of women as spies.

Both the North and the South used female spies in various ways throughout the war. Unsuspecting generals, soldiers, and military intelligence officers on each side had no idea they were being watched carefully by turncoat women in their midst. In this list, you’ll learn all about ten fascinating women who served as spies during the Civil War. They risked their lives to help their side in the vicious four-year-long battle. Some of their stories are the stuff of movies. Now, more than 150 years later, historians still marvel at what they did to gather intelligence for their causes.

Related: 10 Famous People Who Were Secretly Spying on Us

10 Antonia Ford

Antonia Ford was part of a well-off Virginia family prior to the Civil War. She was an educated woman when the conflict broke out, too, having earned a degree in literature from the Buckingham Female College Institute. That alone put her in the upper crust of accomplished women at the time of the war. And then, as the battles began to rage, she took a step nobody else saw coming.

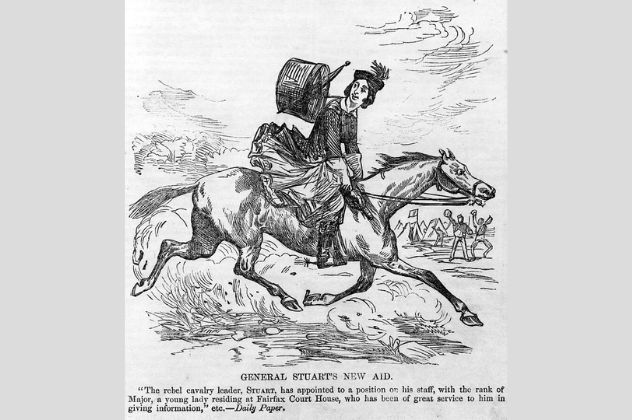

At first, informally, Antonia passed along little bits of military intelligence she’d heard from Union soldiers. She shared the info with Confederate lieutenants and even General J.E.B. Stuart. Realizing her value to the South’s cause, Stuart had Antonia commissioned as an “aide-de-camp.” In his order, he demanded Confederate men regard Ford as a woman to “be obeyed, respected, and admired.”For months, Antonia worked her contacts—including a Union spy—and ferried information to Stuart.

By 1863, Ford had shuttled so much information to Confederate generals that her spying was considered to be a decisive factor in Captain John Mosby’s win at Fairfax that year. Mosby took 33 prisoners in the vicious battle, including Union Brigadier General Edwin H. Stoughton. But Antonia’s personal luck would soon run out. A female Union spy by the name of Frances Jamieson tricked Antonia into revealing her decree from General Stuart. Union soldiers swooped in to arrest her, and Ford was hauled off to prison.

Her story doesn’t quite end there, though. Amazingly, despite spying for her Confederate backers during the war, Ford fell in love with a Union major named Joseph C. Willard during her imprisonment. She gave up spying and married Willard. After the war, they had three children together. She lived out the rest of her life in quiet calm but forever was known as the South’s unlikely “Super Spy.”[1]

9 Pauline Cushman

Pauline Cushman was working as an actress in New Orleans when she married a man named Charles Dickinson. Not long after the Civil War began, Dickinson died, leaving Pauline rudderless and adrift. She joined an acting troupe that made it up to Kentucky in the middle of the war. By 1863, she was offered $300 from two Confederate soldiers to give a toast to the South on stage. Behind the scenes, she was a Union supporter—as was much of the rest of her troupe.

So she went to a Union Colonel named Henry Moore to inquire about whether to accept the offer. He told her to do it, she did it, and then she got fired from the acting company. But the insider connection to those Confederate soldiers kicked off a new career for Pauline. Impressed by Cushman’s diligence and attention to detail, Colonel Moore hired her on as a Union spy.

Quickly, Pauline was sent to Nashville to carry out her duties. There, she ingratiated herself with local Confederate soldiers and Southern businessmen. She passed along bits and pieces of information to Union soldiers on the front lines throughout the rest of the battle. Her acting talents worked wonders during the last several years of the war. She was able to pretend to be somebody she wasn’t, quickly build trust with a mark, and learn of troop movements or logistical plans.

Many of her tips passed through to Union generals, who used them with great success in campaigns across Tennessee. At one point near the end of the war, she was finally caught by Confederate intelligence officers and arrested. They sent her to prison and ordered her to hang. At the last minute, though, Cushman was saved by the grace of a higher power. When the war ended, she was freed.

Sadly, the rest of her life didn’t turn out so well. She continued to act, but she never found fame or lasting fortune from the pursuit. Instead, all she got was a morphine addiction. By the time she died three decades later, in 1893, she had performed for the likes of PT Barnum. That was an incredible and unique achievement, but it didn’t bring her financial success or popular adulation.

She died penniless and struggling with seeking day after day of that persistent morphine fix. Former Union soldiers wanted her buried with the military honors she’d earned during the Civil War, but that never happened. Today, Pauline’s amazing wartime exploits are mostly lost to history.[2]

8 Mary Richards Bowser

Mary Richards Bowser was a Black woman born into slavery in Virginia in the middle of the 19th century. Much of her early life is lost to history, and it’s unclear entirely how or where she was raised. But the woman—who is also sometimes known to historians as Mary Elizabeth Bowser or Mary Jane Richards—was undoubtedly a slave laborer until she was freed by another woman named Elizabeth Van Lew in 1851.

For the next ten years, even though the Van Lew family ridded themselves of the disgusting act of slavery, many of their former slaves stayed nearby to work on the farm and make money. Bowser was one of those women, and she built a close connection with Elizabeth Van Lew. Thanks to Van Lew’s oversight, Mary Bowser eventually received an education. When the Civil War broke out, she immediately backed the Union cause. And that’s where things got really interesting.

Van Lew was no Southern supporter herself, but she had connections right up to the top. Quickly, she realized she might be able to parlay those connections into a way to help the North win the Civil War and eradicate slavery in America forever. So in the final year of the war, Van Lew got her former slave a job in Jefferson Davis’s “Confederate White House” in Richmond, Virginia.

There, Davis and his cabinet members would routinely and openly discuss Confederate wartime policy. Bowser would stand by, serving the men with drinks and food, and listening carefully to the conversations. Then, she would go back to Van Lew and other Union sympathizers and report what she heard. Through it all, Bowser’s strong ear and good memory helped the Union put the final nails in the Confederacy’s metaphorical coffin. Before 1865 ended, the war was over—and Bowser played no small part in it.

After the war, Bowser’s whereabouts are again mostly lost to history. She appears to have spent a few months giving talks to others about her experience as a spy. And in 1867, records indicate she helped found a freedman’s school down in Georgia. At some point after that, she was said to have joined her husband in the West Indies as they struck out to make a new life away from America.

Nobody is sure what happened to her after that. But at least one thing is certain: Bowser was instrumental as a former female slave spying secretly from right under the noses of the Confederacy’s most powerful men.[3]

7 Fannie Battle

Mary Frances “Fannie” Battle was born in Davidson County, Tennessee, in 1842. She was one of several children born to a wealthy plantation owner in the Nashville area. He sent Fannie and her brothers and sisters to a local prestigious school for their education. There, Fannie excelled at her studies. But on the eve of the Civil War, she was called back home.

While she and her sisters settled in on the plantation and prepared to ride it out, her brothers and father went off to fight for the Confederacy. During the brutal war, her dad was taken prisoner by Union soldiers. Then, two of her brothers died in separate skirmishes while fighting for the South. Fannie and her family became enraged at these losses. So, she and one of her grieving sisters-in-law decided to take action.

Their plan was to do what little they could, since they weren’t able to fight for themselves. So they became spies for local Confederate battalions. They would woo Union soldiers passing through and lavish them with praise and romantic attention. Then, they would try to uncover little details about the Union Army’s plans in Tennessee.

For a while, Fannie was somewhat successful in this role. But in 1863, she was caught smuggling key Union papers while en route across Tennessee. The Northern army arrested her and shipped her off to a jail in Washington. For Fannie, the war—and her spying career—ended there.

Interestingly, Fannie actually became far more famous later in life for a completely separate second act. In 1891, Battle was walking along one day in Nashville when she came upon a crowd. They had been circled around a little boy who had been hit by a wagon. Fannie cared for the boy, and quickly learned of his situation. The boy’s father had abandoned the family, and the child, his five siblings, and their mother were struggling to survive.

Learning that sob story, Fannie got an idea. She immediately rented a room near where the mother worked long hours at the cotton mill. In the rented house, she created Nashville’s first-ever daycare for children. For the next 30 years, it expanded into larger spaces serving more mothers and families. By the time Fannie died in 1924, the Fannie Battle Day Home for Children was a well-known and much-beloved Nashville institution.[4]

6 Mary Edwards Walker

Mary Edwards Walker was a rough-and-tumble woman ever since her childhood. She notoriously wore men’s clothes while doing hard work around her family farm in upstate New York. Then, she made history by becoming one of the first-ever women to earn a degree from Syracuse Medical College in 1855. When she got married shortly after that, Mary refused to say the word “obey” in her wedding vows. She rankled wedding guests when she wore trousers to the ceremony, too. And it was the talk of the town when locals learned she was going to keep her last name despite being a married woman.

In 1861, when the Civil War erupted down south, Mary rushed to join the effort. Despite her medical training, and the North’s need for trained doctors, they turned down her request to serve as a Union Army surgeon because of her gender. Undaunted, Mary moved south on her own. Eventually, she hooked up with a Union military outfit in Virginia in early 1862.

From there, Walker followed Union military outfits all across the South. There are records of her working as a surgeon in places like Tennessee, Ohio, and Georgia during the war. She volunteered most of her time there but eventually got a paid position as a surgeon when the list of available men ran dangerously low. The whole way through, she would brazenly cross the battle lines and treat wounded Confederate soldiers, too.

At first, the Union Army resented this. Then, they figured out they could use it to their advantage. So, they started pushing Mary to pick up information about Confederate battle plans from the soldiers she was treating. After several years of grueling work and secret espionage, she was finally arrested by a suspicious Confederate battalion. She spent months in an awful southern prison before being released in exchange for a group of captured Confederate doctors near the end of the war.

She did so well by those Union intelligence officers throughout her service that after the war ended, she earned a Congressional Medal of Honor. With that award, she made history: Mary Edwards Walker was the first woman to ever receive that impressive credential. Her later years after the Civil War proved to be interesting, too. She tried to vote in the 1870s—of course, it was illegal for women to vote then—and was arrested for both that and cross-dressing during the decade after the fight.

She caused so much trouble for politicians that one successfully got Congress to revoke her Medal of Honor in 1917. Mary died two years later, having never given up the award, though. And even though it was “officially” taken back upon her death, she got the last laugh. In 1977, her descendants successfully convinced Jimmy Carter to restore the honor of the late, great Union spy.[5]

5 Nancy Hart Douglas

Nancy Hart Douglas was one of the Confederacy’s most successful and most notorious female spies. Her story started in 1861 after her brother was shot and killed by Union forces. Late that year, she was in her West Virginia hometown when she saw a group of Union soldiers marching past. “Hooray for Jeff Davis,” she yelled at the soldiers.

The Northern boys fired at her, but she wasn’t hit. The adrenaline excited her, and she was hell-bent on avenging her brother’s death. So she joined a guerilla group of southern backwoods fighters called the Moccasin Rangers. Then, with their ranks depleted, the Confederate Army allowed her to join their forces and fight.

While fighting it out with the Confederates late in 1861, her troop was captured by the Union Army. For a while, Nancy was held in prison. The northern soldiers got sloppy with their security, though. Thinking the woman wasn’t a threat to them, they began to let key details slip around Nancy. When they released her after a few months, she took every one of those details back to the Confederates. Amazed at her reliable memory and detailed information, the Southerners wanted more from her. So they decided to farm her out once more—this time more formally as a spy, rather than as a female soldier.

In 1862, Nancy put her next plan into place. She disguised herself as an old woman living in a cabin on a heavily-traveled path. Union soldiers came through and forced their way inside to commandeer some food. Once there, Nancy—pretending to be a little old lady—took in information from the soldiers and memorized it. She relayed the details to waiting Confederates.

But soon, an eagle-eyed Union colonel realized he’d seen Nancy before. The colonel returned to the house, arrested Nancy, and imprisoned her at Summersville. She wasn’t content to ride out the rest of the war in jail, though. Nancy stole a guard’s gun, shot the man, and escaped on the presiding Colonel’s horse. Back home again, she settled in for good. She married after the war and lived out the rest of her life as a “Civil War heroine” notorious for her unique role in West Virginia history.[6]

4 Emeline Piggot

Emeline Piggot was born to a large, well-known family in eastern North Carolina. By the time the Civil War came around, her family had become intimately involved in the fighting. Emeline couldn’t serve in battle, but the war still came to her. A large battalion of Confederate soldiers set up camp across the street from her family’s home. She quickly became alarmed at the squalor and awful conditions in which they lived. That horror, combined with the tragedy of losing her boyfriend in a violent battle with Union soldiers, put her firmly against the North.

Piggot was a good-looking young woman, and so she chose to use that to her advantage. She would host ostensibly pro-Union parties in her home. However, once soldiers and Union supporters showed up, she’d mine them for information.

In some cases, she stole documents, medicine, and troop movement papers. She would smuggle them to nearby Confederate troops. If she were ever stopped by Union soldiers, she knew how to lay it on thick. She would flirt with them and act coy until they let her go without learning what she was hiding under her large hoop skirt.

In addition to the parties, Emeline would distract Union soldiers walking along the highways near her home while her brother would sneak around and bring food to Confederate troops beaten down in the brush. After several years of spying, hijinks, and trouble, the Union Army finally arrested Piggot. They jailed her and tried to haul her off to court, but she managed to escape several trials. She even successfully fled from an attempt on her life later in the war. After the fighting concluded, she supported the losing side right up until her death nearly sixty years later.[7]

3 Charlotte And Virginia Moon

Virginia Moon was always a so-called tough cookie. When she was just a schoolgirl in Ohio, the Civil War broke out. Enraged over what she perceived as northern aggression, Moon brought a rifle to school and shot down an American flag. Then, she walked out of class, went to a local store, and scrawled “God Bless Jefferson Davis” on the window. Her antics got her kicked out of school for good. But her rage wasn’t quelled by that mere act of mini-rebellion.

As the war kicked into high gear over the next few years, she took to the road. She was just a teenager, but Virginia traveled all across the mid-South and beyond. She went from Memphis to Cincinnati to Nashville and even as far away as Canada, secretly carrying important papers and war reports between Confederate soldiers and sympathizers. Along the way, she used her feminine charms to her advantage by flirting with Union soldiers and, um, extracting key war information from them.

Virginia wasn’t the only Moon sibling hard at work for the Confederate cause, though. Back home, her sister Charlotte also worked (more informally) as a spy. She went so far as to accept a marriage proposal from an important Union soldier. She buttered him up for war info, just like Virginia. Then, when it came time to marry at the altar, Charlotte made her move.

As the priest asked whether she took the northern man to be her lawfully wedded husband, Charlotte turned him down, ran off the altar, and disappeared back to her southern roots. At that point, Charlotte kicked her spying into high gear. Later in the war, she even managed to board a carriage being ridden by Abraham Lincoln. She eavesdropped as he spoke of battle plans—then passed the news along to Confederate officers.

The war finally came to an end for Virginia early in 1865 when she was arrested by Union soldiers. She pulled a gun on them and could’ve possibly escaped, but they hemmed her in and took the female spy to prison. She went down fighting, though; when she was arrested, Virginia had a key secret Southern war message in her blouse. Unbeknownst to the Union men, she surreptitiously swallowed it to keep it out of their hands.

And after the war, she took up acting. Her past spying skills must have perfectly suited the talent required to play pretend like that. Before she died in 1925, Virginia appeared in several notable movies, including “Robin Hood” and “The Spanish Dancer.”[8]

2 Rose O’Neal Greenhow

Rose O’Neal Greenhow was a master at building and maintaining relationships. When she was a teenager, years before the Civil War, she got to know a series of important politicians around Washington, DC. Then, in the 1850s, she expanded her contacts among families in the area as she raised a half-dozen children of her own. Tragedies struck throughout that decade, though, as several of her children and her beloved husband all passed away.

So by the time the Civil War came up in 1861, Rose had few family members tying her down and a wealth of contacts in her proverbial Rolodex. A strong supporter of the Confederacy and a sharp woman all around, Rose chose to go into the spying business. She used her beauty and guile to flirt with Union soldiers.

Upon gaining little bits of battle information, she would secretly pass notes along to Confederate soldiers. She was so clever and handy that she would even sew important documents into her clothes and hide messages in her hair. That way, she was never caught for spying when questioned by northern soldiers out in the street.

After several years of successful spying, the Union Army finally caught up with her. It took none other than soon-to-be-famous detective Allen Pinkerton himself to make the case against her. But even while in jail, Rose didn’t go quietly. She was caught passing on information to other Confederate sympathizers several times while in prison. Her eight-year-old daughter was even caught smuggling information into Rose that had been scrawled in small letters on candy wrappers.

As the war was ending, the Union released Rose. Her DC connections paid off for her once more when an influential American sent her off to Europe on a book deal. There, she was paid $2,000 in solid gold to write her memoirs. The book was a hit, but Rose wasn’t long for the world. On the way back home, right before the end of the war, the ship she was on was rammed by an aggressive Union gunboat. The vessel sank, and Rose went right down along with it. She had sewn up the gold pieces into her dress for the voyage home, and sadly, the weight of the precious metal was too much for her to overcome once in the water.[9]

1 Belle Boyd

Belle Boyd was born into privilege in Virginia and was just a teenager when the Civil War broke out. She might never have become a Confederate backer, and especially not a spy, but something fateful happened to her early in the war. Union soldiers occupied the area around her home in early 1861. One northern soldier walked right into her house, saw a Confederate flag in the window, and yanked it down. Then, according to legend, he insulted Belle’s mother.

Enraged, Belle pulled out a gun and shot the man to death. Amazingly, she was not tried for murder after a local board of inquiry refused to indict her. But the Union Army still posted sentries near her house and kept close tabs on her activities. That only angered Belle further, so she took it out on the Union as best she could: by spying for the South.

Over the next four years, Boyd’s spying exploits were so notorious that she would become known by nicknames like the “Cleopatra of the Secession” and the “Siren of the Shenandoah.” Some modern historians even now recognize her as “the most infamous spy of the Civil War.” Her acts were worthy of a movie. As we’ve seen with many other female spies, Belle used her beauty and feminine daintiness to extract information from Union soldiers.

But she was also tougher than most men. At night, she would creep through Union camps and look for guns and ammunition laying around. Upon finding rifles and other arms, she’d steal them and rush the pieces back to Confederate troops. When she felt like she’d be caught red-handed, she simply buried the rifles and later passed the locations along to southern soldiers to dig up when in need.

She was able to ingratiate herself into Union elite culture. Then, she used the connections to eavesdrop on Union generals. In one notorious instance, she hid in a hotel room while several northern leaders were discussing a march across Virginia. In another case, she escaped Union guards and survived being shot at while rushing to deliver a key piece of information to Confederate General Stonewall Jackson.

Belle was arrested on spying charges multiple times, and each time, she was threatened with execution. But she simply kept on spying for the Southern cause. At the end of the war, when the North was beyond fed up with her antics, Belle secretly married a Union officer and escaped unharmed to London. She ended up writing her memoirs about that crazy period in her life while living there. Years later, she returned to the United States and lived in Wisconsin. In 1900, a heart attack did what no Union soldier could do, and Belle died at 56 years old.[10]

[ad_2]

Source link

Comments are closed.