[ad_1]

This article is an on-site version of our Unhedged newsletter. Sign up here to get the newsletter sent straight to your inbox every weekday

Good morning. Fed chair Jay Powell spoke yesterday, and basically said the same thing as he did at the press conference last week — that is, if the strong economic data keeps coming, more tightening will be in order. The market took this as dovish, which makes some sense. Powell had an opportunity, in the face of strong markets, to strike a more hawkish note. He declined to do so. Have another interpretation? Email us: robert.armstrong@ft.com and ethan.wu@ft.com.

The Fed as threat to financial stability

A lot of people don’t like the Fed. Write an FT article about any imperfect feature of the financial system, you are likely to get a comment saying “it’s the Fed’s fault”. The Fed, according to its detractors, has suppressed interest rates, printed cash, distorted asset prices, encouraged malinvestment, worsened inequality, and increased the odds of a market crash.

The source of these arguments at times undermines their credibility. They are frequently (though not exclusively) made by underperforming value investors, bears who shorted the long bull market, gold bugs, and assorted other malcontents.

This does not make the arguments wrong, though. It is useful, then, when the case against the Fed is framed intelligently by a very reputable voice. Dennis Kelleher and Phillip Basil, of Better Markets, did just that in a report last month, “Federal Reserve Policies and Systemic Instability.” I encourage everyone to read it, if only to crystallise views about Fed policy works. A brief summary of the arguments:

-

Since 2008, Fed rate and balance sheet policy has decoupled asset prices from risk, and encouraged both companies and households to use a dangerous amount of debt. Very low rates mean investors have been “strongly incentivised if not forced into riskier assets, leading to mispriced risk and a build-up of debt”

-

Comparing the decade after the great financial crisis to the decade before, the growth in US debt held by the public was nearly 500 per cent larger, the growth in nonfinancial corporate loans and debt securities was about 90 per cent larger, and the growth in consumer credit — excluding mortgages — was roughly 30 per cent larger.

-

Proof that the central bank had pushed too much liquidity into the market with quantitative easing can be found in the Fed’s own reverse repo operations. “The Fed was pumping trillions of dollars into financial markets and limiting the supply of safe assets on one side of the market and siphoning out trillions of dollars from financial markets through its RRP facility on the other side.”

-

All this created a market excessively dependent on easy money, as the 2013 taper tantrum and the Fed being forced to ease policy in mid-2019 demonstrate.

-

Reversing these bad policies in the face of inflation risks recession, corporate defaults, stress in the Treasury market, and a cracked housing market. The Fed may overreact to these stresses, too — perpetuating the cycle of error.

This charge sheet is not crazy. But it attributes too much power to monetary policy. Central banks do have direct control over the very shortest interest rates. Their influence on long rates — the ones that really matter — is real, too, but is usually indirect, contingent, changeable, and depends on mass psychology (the Bank of Japan’s experiment in direct control over long yields is something of a special case). It may be true that easy money is a necessary condition for an asset bubble, but it is not a sufficient one.

There is case to be made that the Fed follows long rates, rather than long rates following the Fed. A very strong version of this argument was recently made by Aswath Damodaran of NYU. He writes:

If the question is why interest rates rose a lot in 2022, and if your answer to that question is the Fed, you have, in my view, lost the script. I know that in the last decade, it has become fashionable to attribute powers to the Fed that it does not have and view it as the ultimate arbiter of rates. That view has never made sense, because central banking power over rates is at the margin, and the key fundamental drivers of rates are expected inflation and real growth.

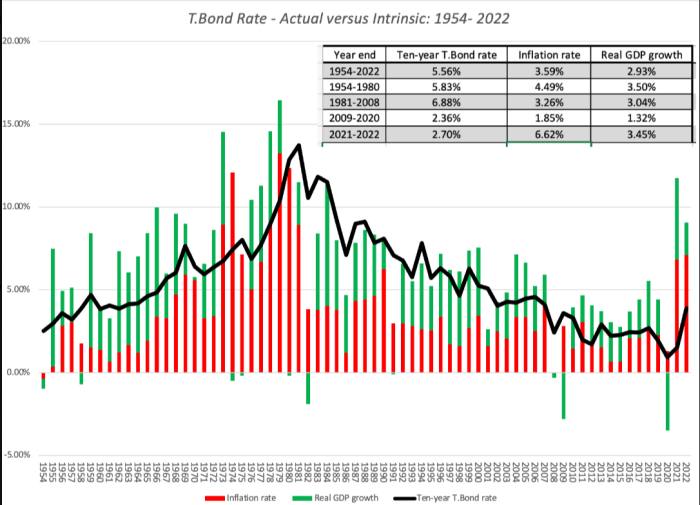

He offers this long-term chart of real GDP growth, inflation, and 10-year yields:

“It was the combination of low inflation and anaemic growth that was at the heart of low rates,” he writes, “though the Fed did influence rates at the margin, perhaps pushing them down below their intrinsic levels with its machinations.” You can quibble with Damodaran’s own account of rates (especially the link between rates and real growth), but the point is that you can’t just assert that Fed policy determined the last decade of very low rates.

We have argued — and still believe — that the quantitative easing, by increasing liquidity in markets, drives asset prices up, through the portfolio balance channel. But, just like rates, market liquidity is determined by a number of factors. Foreign central banks play a role, as do demographics and wealth inequality.

Still, the basic point remains: the Fed was too loose, and now we have a heavy debt burden, expensive assets, and inflation. But remember the reason that the Fed went for loose policy all those years: demand was weak. And there is a very strong, perhaps unanswerable, case that the Fed was a year late to raising rates and tapering asset purchases. But do Kelleher and Basil think that the Fed was too accommodative in, say, 2011-14? Why?

One final point. So far — somewhat to Unhedged’s surprise — the return to a neutral policy stance is going pretty well. Asset prices are down and home sales are falling, but after the run they have had, that seems healthy. Unemployment is lower than ever. The Kelleher/Basil argument will look a lot stronger if we get a proper market crash or a deep recession.

What the Fed might think about financial conditions

The Fed wants to tighten financial conditions to root out inflation. Markets just want an excuse to rally. But markets have a big role in determining financial conditions. This leaves the Fed with less-than-ideal options: tighten monetary policy still further, to whip markets into line, or accept watered-down monetary policy transmission for a while.

Asked about this Fed/markets gap last week, Powell seemed remarkably chill about it all. He’s “not particularly concerned” about “short-term moves” in financial conditions because they simply reflect markets’ dovish opinion of inflation falling quickly. His is not a ludicrous view. Still, one wonders if there’s more to what Powell, and the Fed, is thinking.

A new research note from the San Francisco Fed might hold a clue. The authors, Simon Kwan and Louis Liu, look at a measure of policy tightness called the “real funds rate gap”. This is the difference between the fed funds rate and the Fed’s estimate of the neutral rate (ie, the theoretical interest rate that neither stokes nor suppresses inflation) after both are adjusted for inflation. The bigger the gap, the tighter policy is; the smaller, the more accommodative. Estimates for this cycle’s rate gap (January 2022 to May 2023 below) come partly from the Fed’s latest set of economic projections.

The exercise reveals just how much more dramatic recent monetary tightening looks compared to tightening cycles in the past:

In this cycle, real rates moved way up (rightmost green bar) from a very low baseline (rightmost blue bar) as inflation ran hot. If the Fed’s projections roughly bear out, it will be the most drastic real funds rate gap change — that is, the most screeching tightening cycle — in the postwar era.

This will matter to financial conditions. In the past, Kwan and Liu find that a highly negative rate gap (ie, highly accommodative policy) at the start of a tightening cycle is followed by widening yield spreads and falling stock prices. But based on how vastly negative this cycle’s initial rate gap was, stocks haven’t fallen and spreads haven’t expanded nearly as much as history would suggest they should. Much tighter financial conditions may lie ahead:

When we use this historical relationship to evaluate stock prices at the large negative funds rate gap, stock prices are projected to decline further. The historical relationship between the funds rate gap and bond spreads also calls for more tightening in the bond market . . . past experiences indicate that more tightening of financial conditions could follow.

If you’re at the helm of the Fed, this is reason enough for forbearance. Monetary tightening is only part way through; financial markets could catch up fast, and violently. Recent “short-term moves” in markets just might not be worth sweating. (Ethan Wu)

One good read

RIP to this Australian Shepherd. Good dog!

[ad_2]

Source link

Comments are closed.