[ad_1]

This article is an on-site version of our Unhedged newsletter. Sign up here to get the newsletter sent straight to your inbox every weekday

Good morning. Scenes in Brasília over the weekend brought back painful memories of two years ago in Washington. Trump might be receding into the rear-view mirror, but anti-democratic populism is not. Send me some good news, please: robert.armstrong@ft.com.

The news on wage growth was not all *that* good, everyone please calm down

The markets saw last Friday morning’s jobs report — and in particular its data on slowing wage growth — as more evidence that inflation will continue to cool rapidly and the Federal Reserve will be able to begin cutting rates before the end of this year. The S&P rose 2.3 per cent on the day and the two-year Treasury yield fell 19 basis points, representing almost an entire rate hike falling out of investor expectations. The futures market now prices a 95 per cent chance that the Fed’s policy rate will be below the central bank’s stated target of 5.1 per cent at the end of 2023.

Regular readers will not be surprised that Unhedged does not think the news was quite as good as all that, both because of our congenital ill temper and because we have argued in the past that the final rounds of the inflation fight will be the toughest.

The economic data remains equivocal, ambiguous, and confusing. Yes, a decline in wage growth to 4.6 per cent in December, and revision to earlier months’ growth rates, leaves us with a steadily slowing trend in wage growth that reaches back to May — even if the current growth rate is uncomfortably high:

New jobs added have fallen every month since August, too. But adding well over 200,000 jobs a month, with ample openings and a high quit rate is not deflationary, even in combination with the surprise weakness in activity surveys reported last weak. Christian Keller at Barclays thinks markets should put away the champagne until the data is easier to read:

A combination of rising employment and slowing wage growth would certainly be good macro news, potentially rendering the Fed less hawkish. We warn, however, that [the average hourly earnings data] is notoriously noisy and prone to distortions from ongoing shifts in the composition of payroll employment back to lower-paying service sector jobs, as strong labour demand draws less-skilled workers . . . Next week’s Atlanta Fed wage tracker and later the Q4 Employment Cost Index (January 31) control for compositional effects, which should shed more light

Don Rissmiller of Strategas also emphasised compositional issues:

Average pay can be affected by mix shifts: the economy is adding more part-time vs. full-time jobs. But workers appear to be choosing part-time (ie, these are not mainly part-time for economic reasons). There’s still a mismatch in labour supply vs. labour demand. A tight labour situation will continue to threaten future wage pressure . . . Price inflation is peaking, but wage inflation looks sticky.

Rissmiller thinks that chances are good that what kills off wage inflation is a recession.

Matt Klein, over at The Overshoot, makes another important point: the marked slowdown in wage growth can only be deflationary if it is accompanied by lower churn in the job market. If inflation is under control, demand must be below supply. When someone loses their job, their contribution to demand falls as they tighten their spending, but their contribution to supply falls to zero — they’re unemployed! So the job losses alone are not deflationary. The employed need to be scared into accepting the jobs and wages they are receiving now, and watching their budgets:

Forcing people out of work does not, by itself, reduce pressure on prices. Scaring people into spending less relative to the value they generate does. Thus, from the Fed’s perspective, the ideal scenario is that workers lose their leverage to ask for bigger raises without anyone actually getting fired. But that (relatively) benign outcome is only going to happen if job market churn normalises. Unfortunately, the latest data imply that this is still a ways off.

The number of job vacancies relative to the number of people actively looking for work is still about double what it was on the eve of the pandemic . . . More importantly, given the tighter relationship to wage growth, is the number of people quitting their job for better prospects elsewhere. While the number is down quite a bit compared to the peak at the end of 2021, there has been no real change since June.

Olivier Blanchard is also focused on openings. Back in November, he tweeted that the US would soon be experiencing “false dawn” on inflation as commodity prices have started to fall, but that wage growth remains consistent with inflation persistently above the Fed target. In an email yesterday, Blanchard wrote that despite the latest data, he had not changed his mind. We wrote:

The issue is, once energy/food prices have stabilised, can we maintain stable inflation with an unemployment rate of 3.5 per cent? I believe, based in particular on my work with Summers on the Beveridge curve [the relationship between unemployment and job vacancies] that we need a higher unemployment rate, perhaps around 4.5 per cent.

The recent wage numbers suggest that maybe I am too pessimistic. I do not think so, but we shall see. If I am right, then the Fed has to slow down the economy, or given the lags, believe that the economy will slow down, before it starts decreasing rates.

Everyone, Unhedged included, wants inflation to get to target without having a recession. But that is still not the most likely outcome.

Gold & central banks

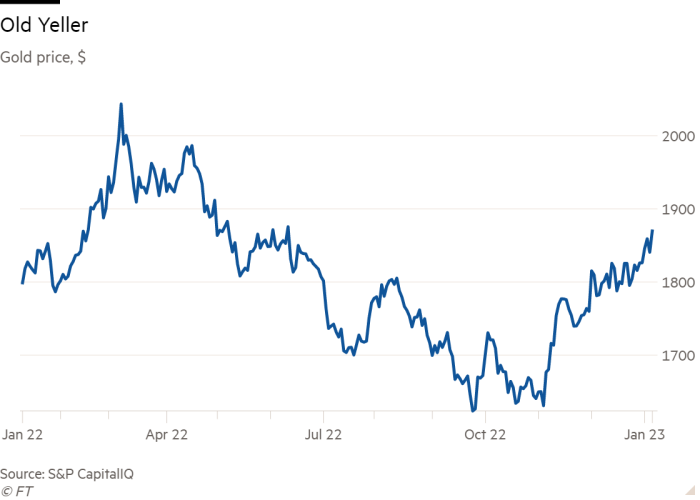

In a blighted investment landscape, gold has done pretty well over the past 12 months:

The strong performance since August is particularly impressive because it has occurred while real interest rates have been solidly positive — in the range of one and a half per cent, as measured by the yield on 10-year inflation-protected Treasuries. Usually gold moves inversely with real rates, which reflect the opportunity cost of owning an expensive, inert metal.

One of the key reasons for the rally, as the FT reported at the end of last month, is the increase in demand from central banks:

Central banks are scooping up gold at the fastest pace since 1967, with analysts pinning China and Russia as big buyers in an indication that some nations are keen to diversify their reserves away from the dollar . ..

In the third quarter [of 2022] alone central banks bought almost 400 tonnes of gold, the largest three-month binge since quarterly records began in 2000.

Does the increase in central bank appetites mark a lasting shift in the supply/demand balance? Jon Hartsel, CIO at Donald Smith & Co, thinks so. He notes that demand

. . . has been consistently positive around 500 tons per year since the great financial crisis (vs. mine production of ~3,500 recently), but it came in at a record 400 tons in Q3 alone, and its quite possible it could average 750-1,000 tons per year going forward given the geopolitical backdrop where gold’s utility as a neutral (non-USD) reserve asset to Russia, China and Middle Eastern countries became more apparent in 2022.

James Steel, precious metals analyst at HSBC, strikes a more cautious tone. He thinks that the recent strength in the gold price has to do with expectations of Fed rate cutting as well. While acknowledging that central bank demand is higher and likely to stay that way, he thinks three points need to be kept in mind:

-

Central banks are not preparing to shun the dollar. The gold purchases are better thought of as marginal diversification, in a form which does not require a commitment to other global currencies, all of which have their own problems.

-

Some 50 or 60 per cent of physician gold production goes into jewellery in developing economies such as China and India, where consumers are very price sensitive. As the gold price rises above $1,800 or so, demand ebbs quickly.

-

Central banks are price sensitive too, and will moderate their gold purchases as prices rise.

Unhedged is a bit sceptical about gold as an investment, for the standard reasons (no yield, not productive, overrated inflation hedge) but we’ll be watching more closely now.

One good read

Wait, who?

[ad_2]

Source link

Comments are closed.